21 – The Oil Storage Tank Farm

| < 20 – Land Reclamation, Excavation and Dredging | Δ Index | 22 – Post WW2 modifications > |

When a dockyard at Rosyth was first considered, all of the Royal Navy’s warships were powered by coal. Especially Welsh anthracite (also known as steam coal) which burned cleanly with little tar, ash or smoke.

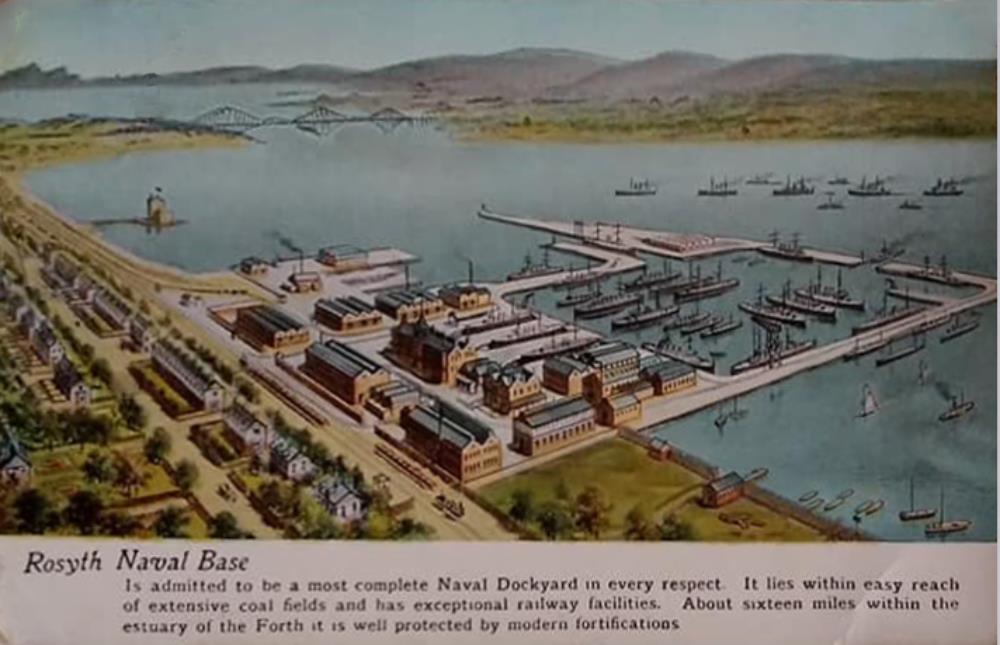

This postcard from c1910 highlights the proximity of Rosyth to the major coal fields along the Forth

The large triangular dock are next to the entrance lock was intended as a coaling point for the fleet.

But coal was difficult stuff to handle.

HMS “Queen Mary” was completed in 1913, the last Royal Navy battlecruiser built before the First World War. She was powered by two paired sets steam turbines fed steam by 42 boilers in seven boiler rooms, producing 83,000 shp (62,000 kW) at full power giving her a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h).

HMS Queen Mary

HMS Queen Mary

She carried a maximum of 3,600 tons (3,660 t) of coal and 1,170 tons (1,190 t) of fuel oil to be sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. Her range was 5,610 nautical miles (10,390 km) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h).

All hands were involved in fuelling a ship by carrying bags of coal each weighing 1½cwt (1cwt is a hundred weight or 112 lb. So each bag weighed 168lb or 76kg.) 3,600 tons of coal means 48,000 bags of coal to be hoisted from a barge or collier onto the deck of a ship, and then carried on men’s backs to the fuel bunkers distributed throughout the ship.

Coaling a ship was exhausting filthy work. Once the coal was on board it had to be shovelled by hand from bunker to boiler room and then into the boilers. Teams of stokers manned the boilers while teams of trimmers move the coal through the ship – keeping the shipped trimmed – i.e. level.

Queen Mary’s war-time crew numbered 57 officers and 1205 ratings. Of the 1205 ratings, 555 were stokers and trimmers.

Refuelling at sea was impossible, meaning that a quarter of the fleet might be forced to put into harbour coaling at any one time. Providing the fleet with coal was the greatest logistical headache of the age.

Advantages of Oil over coal

Oil offered many benefits. It had double the thermal content of coal so that boilers could be smaller and ships could travel twice as far. Greater speed was possible and oil burned with less smoke so the fleet would not reveal its presence as quickly. Oil could be stored in tanks anywhere, allowing more efficient design of ships, and it could be transferred through pipes without reliance on stokers, reducing manpower. Refuelling at sea became feasible providing greater flexibility for the fleet.

In 1911 a new class of fast battleship was being designed. These were required to be able to outmanoeuvre and cross the T of the German fleet, this needed a speed of 25 knots, or at least four knots faster than possible at the time from coal-fired ships. Churchill concluded, “We could not get the power required to drive these ships at 25 knots except by the use of oil fuel.”

In 1912, the decision was taken that the new Queen Elizabeth-class battleships would burn oil only. Once this decision was made, Churchill wrote, it followed that the rest of the Royal Navy would turn to oil: The fateful plunge was taken when it was decided to create the fast division. Then, for the first time, the supreme ships of the navy, on which our life depended, were fed by oil and could only be fed by oil.

Hence the need for the oil tank farm adjacent to the dockyard. This was built on reclaimed land.

You can read more about the transition from Coal to Oil in This Paper.

The oil fuel depot, with a concrete tank (for 250,000 tons) and 37 steel tanks (each for 5000 tons)

The oil fuel depot, with a concrete tank (for 250,000 tons) and 37 steel tanks (each for 5000 tons)

This long jetty provided a fuel line to ships in deeper waters of the main channel.

This long jetty provided a fuel line to ships in deeper waters of the main channel.

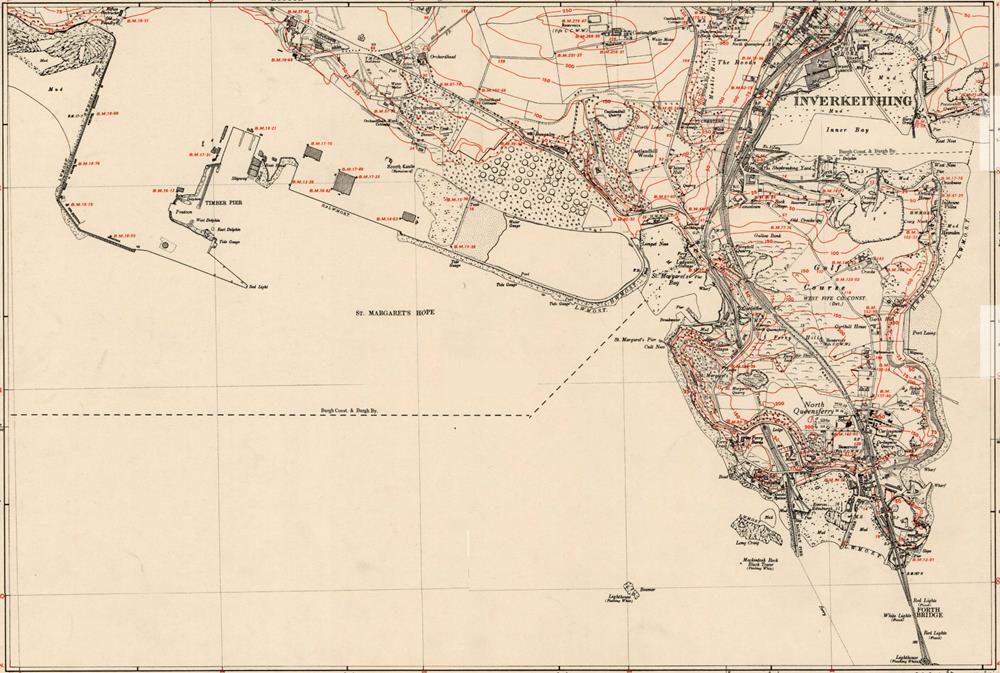

The tanks first appeared on an OS map in 1952. Earlier OS maps ignored them or labelled the large concrete tank as “Rosyth Quarry”. Even the 1952 map is reticent about details of the dockyard.

The concrete tank was built from 1915 to 1918 and consisted of a concrete retaining wall on the four sides, stretching 160m (525 ft) and 10 m (33ft) tall, with a central concrete wall that turned it into two separate tanks. These were then roofed using timber joists and boards covered by roofing felt.

The reworking of the structure that started in 1936 and was completed in 1942 to ensure that it could withstand the effects of potential air attacks.

The wooden roof was removed and the side walls were protected by an additional wall 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in depth that thickened towards the base, where the total thickness ended up as being 8m (26.3ft). The original walls were also increased in height by 2m (6.6 ft).

To hold up the new roof over the structure, a total of more than 3,000 1. m (3.9ft) diameter columns were installed inside the tanks to support the protective roof structure that was expected to weigh 500,000 tonnes when complete. This consists of a 7.5m (24. ft) deep sandwich of alternating layers of heavily reinforced concrete and sand. Each layer of concrete was poured to a maximum depth of 0.8m (2.6ft). The whole structure covers an area of 9.5 acres and contains a total of 1 million tonnes of concrete with 2,200 km (1,380 miles) or rebar.

Demolition of the Oil Tanks

The area which held the steel tanks was cleared and used a worksite for the construction of the Queensferry Crossing. Demolition of the concrete tanks commenced 2008. The material was used for foundations and drainage material in a number of local developments including the A8000 upgrade, the new port access road in Rosyth and housing developments in Dunfermline.

Demolition of the oil tanks

Demolition of the oil tanks

| < 20 – Land Reclamation, Excavation and Dredging | Δ Index | 22 – Post WW2 modifications > |

top of page