1863 – Birth of the Submarine Mining Service

| < Intro | Δ Index | 1887 – Submarine Mining in the Forth > |

War Office Investigations

In 1863, the War Office established a committee to investigate the potential of controlled mines in defending “our channels.” A number of experiments and trials were conducted to determine the best type of explosive, the amount required, the depth of deployment and the nature of the coastline and tidal flow.

Recommendation

By 1870 they concluded that electrically controlled minefields should be deployed to protect the Royal Navy bases on The Medway (including the Thames), at Portsmouth, Plymouth, Pembroke and Cork. They were also to be deployed at our overseas naval base: Bermuda, Malta, Halifax (Nova Scotia), Jamaica, Mauritius, Trincomalee (Sri Lanka), Singapore and Hong-Kong. And finally to protect commercial and other ports at home: Aberdeen, the Tay, the Forth, the Clyde, the Tyne, Hull, Yarmouth, Harwich, Falmouth, the Severn and Liverpool.

They decreed that:

1. Mines should only be placed under the protection of the guns of ships or forts.

2. They should be placed about 1000 yards in front of these guns.

3. The minefield should be protected by armed vessels to safeguard against sabotage.

4. The controlling electrical cables should be protected on the seabed with parallel chains, to prevent then being dragged out of position.

5. The locations of mines and stations should be kept secret from charts and maps.

6. Dummy mines should be liberally deployed to deceive the enemy.

7. Electric lights should be deployed for night-time operations.

8. The most important must have diving apparatus and divers to examine deployed mines without the time and expense of raising and redeploying them.

A series of experiments in from 1874 to 1876 was conducted at Gosport near Portsmouth using an old hulk, the Oberon. She was fitted out with equipment to simulate a state-of-the-art war ship, and used to determine the best way to destroy such a ship using a minefield. This resulted is a standardized set of specifications for the types of mine, size of charge and layout of the minefield.

The initial focus was on the Royal Navy bases, and over the period 1870 to 1880, five Royal Engineer companies were established. They set-up mining stations on the Medway at Chatham (the Headquarters of the submarine mining service), Sheerness, and Gillingham; the Thames at Gravesend; Portsmouth; Pembroke; and Cork, and overseas stations at Bermuda, Halifax and Malta. Central stores were established at Woolwich, and 1,800 mines were purchased by the end of 1872.

Further experiments were undertaken to determine the speed at which minefields could be deployed, how effective they were against wooden- and iron-hulled ships, how to defend them against attacks by mine-sweepers, and how reliable individual mines were once deployed in a minefield.

These experiments highlighted the need for powerful searchlights to spot enemy ships and minesweepers at night. Initially the electricity to power the searchlights was produced on-site using steam-driven generators. It took about 2-3 hours for the boilers to raise the necessary head of steam. In 1894, paraffin-oil-powered engines were introduced to drive the generators. These could be started and brought up to speed in about 20 minutes.

In 1897, parabolic reflectors and improved lenses were introduced for the searchlights.

Finally “it was determined that as the role of the Royal Navy was the active defence of Great Britain, no Naval vessels should be tied to the shore, so the sedentary defence of the sea and ports should be in the hands of the Army, and in particular the Royal Engineers.”

The Royal Engineers invented military diving in 1838, and taught the first Royal Navy divers.

In 1911, the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers became the first unit responsible for manned balloons, airships and kites. The Air Battalion became the Royal Flying Corps in 1912, and subsequently the Royal Air Force in 1918.]

Manpower issues – Militia and Volunteers

The nature of the submarine mining service created some manpower issues. The service required a number of dedicated teams trained and regularly practised in a particular set of skills, each tied to a specific geographical location. These teams were on long-term standby, as the minefields would only be deployed in time of war. Not an efficient use of full-time soldiers.

This problem was eventually solved by the raising of Militia units to defend the Navy bases, and Volunteer Corps to defend commercial ports, both overseen by a dedicated unit of full-time Royal Engineers, the Coast battalion.

[The Militia were originally reinforcements for the regular standing army, with each county being obliged to provide a number of men. By the 19th century, the element of compulsion had disappeared; men would volunteer and undertake basic training for several months at an army depot. Thereafter, they would return to civilian life, but report for regular periods of military training (usually on the weapons ranges) and an annual two-week training camp. In return, they would receive military pay and a financial retainer, a useful addition to their civilian wage. Traditionally the militia were trained as infantry, but in 1852 artillery units were formed.]

Submarine Mining Militia units were formed in Portsmouth, the Needles, Plymouth, the Thames, Medway, Harwich, Milford Haven, the Humber, Falmouth and Cork. They went through a simplified training program, with annual exercises which lasted up to 55 days. Officers were trained in the deployment and management of the mines, while NCOs and men were trained as boatmen and focussed on water work.

25% of the total strength of the officers of a militia division could be attached annually to the local Royal Engineer Company for defence practice of two months during which they took their full share of regimental and mining work.

Officers and men were initially paid Militia pay according to rank. In 1893 they were placed under the general Regulations for Engineer pay, and given rates of pay according to their trade proficiency.

As well as training in the handling of mines, the men had 77 days of preliminary drill including musketry, and then had 55 days annual training – the maximum permissible for the Militia. They were part-time soldiers.

Volunteers

In 1880, with the Royal Navy bases covered, the topic of minefields to protect commercial ports was again on the agenda. The manpower problem was tackled by the formation of a Coast Corps of the Royal Engineers who then trained and oversaw local Volunteer Corps, and the Militia.

Volunteers and Militia went through the same standardised three part training course.

1. Shore work (one month’s duration)

2. Water work (one month’s duration)

3. Electrical work (two month’s duration)

Volunteer officers and men were paid 10s and 5s a day respectively during this training.

By the end of 1891, the Submarine Mining Service comprised:

Regulars: 92 officers and 1272 other ranks

Militia: 68 officers and 1260 other ranks

Volunteers: 1,806 in total (all ranks)

There were volunteer divisions at the Tay, Forth, Clyde, Humber, Tyne, Tees, Mersey and Severn. Submarine Mining defences manned by regulars and militia were eventually in place at 28 Royal Navy bases around the world.

There were 31 mine-layers, 31 launches, 56 other vessels and 47 electric lights sets.

In addition to the specialist mine-laying vessels, open boats were hired from local fishermen to make connections and test the electrical cables that connected the mines to the controlling shore station in each minefield. About 3 or 4 of these boats were required for each mine-layer.

In 1897 a specialised Corps of Electrical Engineer Volunteers was formed to manage the rapidly-growing deployment of electric lights at the Mining Stations.

Practice Sessions

As well as introductory training and annual drill sessions, a vital element of training involved practice sessions. The object of these was to rehearse as far as possible the actual work of laying out a minefield.

Plans of a special minefield were prepared. Mines were drawn from stores, loaded with sand and gravel instead of guncotton. The firing apparatus (detonator in the mine) was prepared and tested. Cables were cut to size. The mines were then deployed, with cable running to the shore station all connected up and tested. Every operation except the actual handling of guncotton and detonation of mines was carefully rehearsed, so that every man was familiar with the various tasks allocated to each work party.

These annual practices usually lasted about three months. At the end of a practice all items were cleaned and returned to stores.

The practice area was usually part of where a live minefield would be deployed, but the actual location of each mine field was kept secret. Plans were held by the War Office and would be issued if war was imminent.

Submarine Mining divisions round the British Isles

Submarine Mining divisions around the world (all at naval bases)

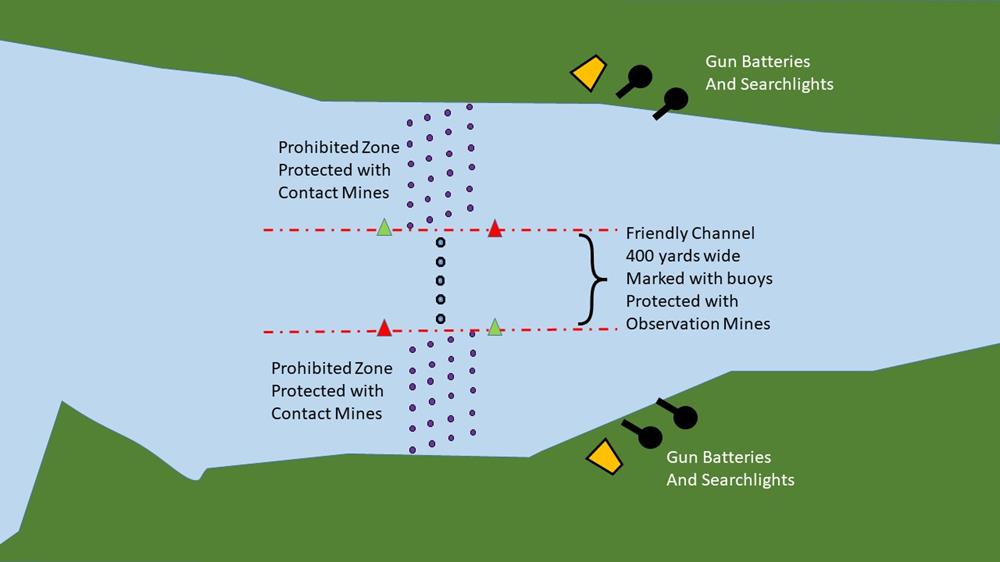

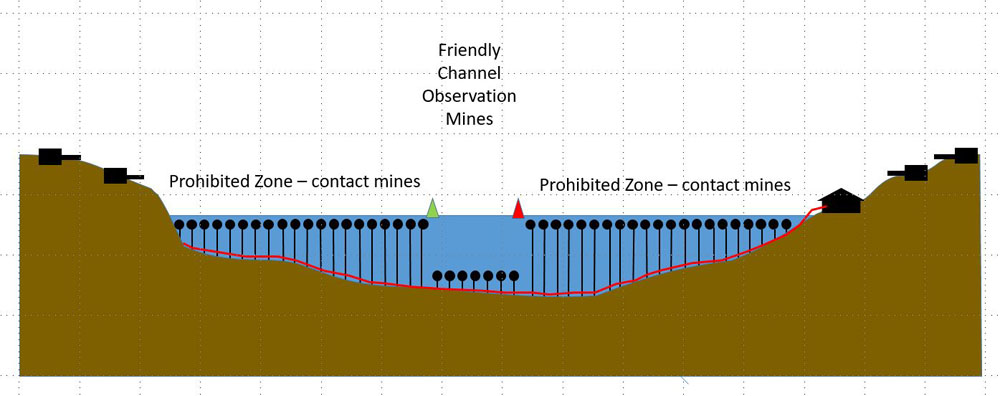

A minefield defending an estuary

This diagram shows how a typical minefield was laid out across an estuary. A 400 yard [365 metres] wide “friendly channel” was marked with red and green buoys. The friendly channel was flanked with no-go prohibited zones seeded with contact mines.

These contact mines were electrically operated. They could be turned off, so that friendly ships would not be destroyed if they strayed into the no-go zone. The contact mines were anchored to the sea bed and set at a depth of a few feet below sea level. They were laid out in off-set lines, so that there was effectively one mine every 25 feet [7.5 metres] making this an impenetrable zone for enemy ships, which would trigger an explosion on making contact with one of these mines. Contact mines are effective at night or in fog or smokescreens, but are at risk of being snagged by friendly shipping and dragged out of position.

The friendly channel was protected by Observation Mines resting generally moored at a depth of 30 to 60 Feet [10 to 20 metres] or resting on the sea-bed in shallow waters. These mines could be detonated by an observer on shore when an enemy ship passed overhead. These observation mines carried a large explosive charge, sufficient to sink a ship, despite not being in contact with it.

The friendly channel was also the target of the shore-based gun batteries, and electric search lights. Enemy ships heading towards a port or up an estuary were forced to sail into the friendly channel or be destroyed by the contact mines. The shore batteries and their associated search lights were able to focus on the friendly channel making it impassable to enemy ships.

The Submarine Miners deployed and managed the minefield and the Searchlights, while the Royal Artillery manned the guns.

| < Intro | Δ Index | 1887 – Submarine Mining in the Forth > |

top of page