Barrage Balloon Sites round North Queensferry

Bob Cubin’s book “No Flight Of Fancy – Reminiscences Of A Balloon Barrage Man” identifies nine barrage balloon sites around North Queensferry. (Extracts from his book form the basis of much of this article.)

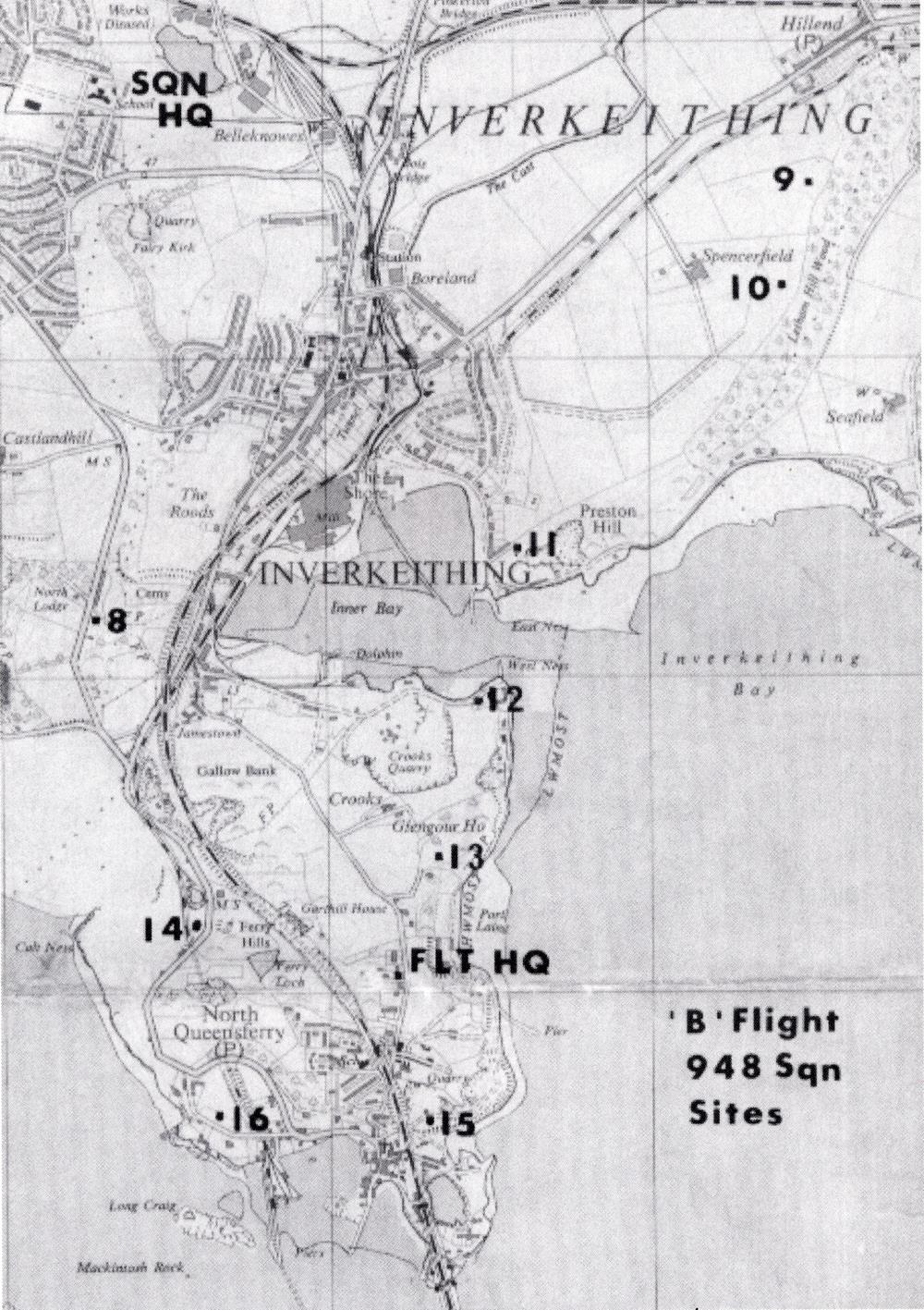

‘B’ Flight site locations.

‘B’ Flight site locations.

These sites were part of the Forth Barrage operated by No 19 Balloon Centre during WWII. The barrage comprising land sites on the Fife and Lothian side of the Forth, and barge sites on the river. The land sites in Fife guarded the Forth Bridge, Rosyth Dockyard, RNAS Donibristle and Methil Docks against air raids.

Introduction

Barrage balloons were developed in the late 1930s as a countermeasure to bombing raids. A set of vertical steel cables attached to hydrogen-filled balloons formed a defensive curtain round the site of any potential target. sites were to be manned by auxiliary airmen, who had been trained weekends

R.A.F. Balloon Command was established in 1938, in anticipation of the need to defend key targets from air raids. In case of war, the balloon sites would be manned by members of the Auxiliary Air Force – factory, bank, local government and office workers who trained at weekends over a period of 12 months by regular members of the RAF.

Later in the war these were largely replaced by WAAF (Womens Auxiliary Air Force) personnel.

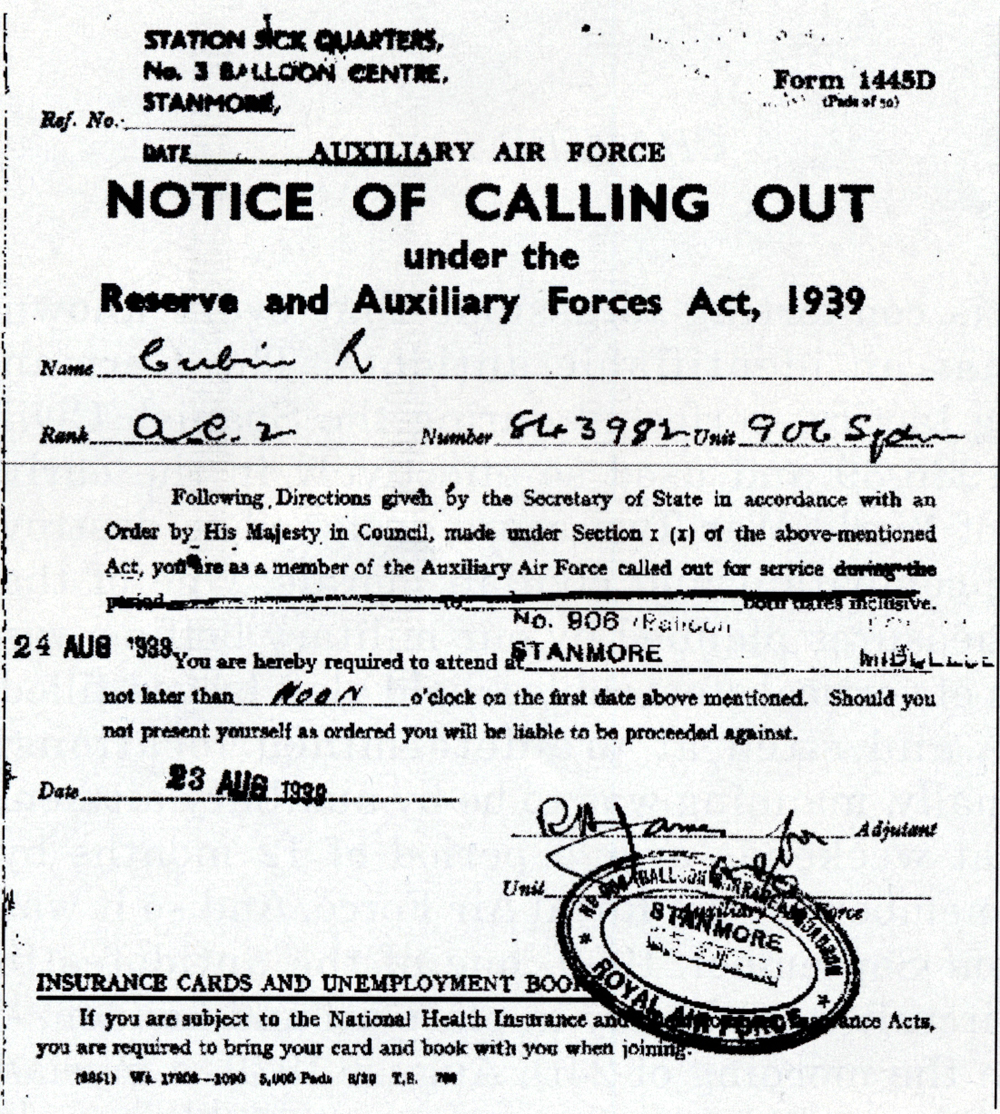

On 24th August 1939, calling-out notices arrived across the Home Counties exhorting the recipients to report for duty at their designated balloon station.

Form 1445D requiring AC.2 Cubin R. to report for duty

Form 1445D requiring AC.2 Cubin R. to report for duty

Bob Cubin’s destination was Stanmore in Middlesex, where he was kitted out and dispatched to London where balloon were deployed at various locations.

Practice Balloon barrage Crew, Stanmore 1939.

Practice Balloon barrage Crew, Stanmore 1939.

Haversacks contain gas masks.

Bob is third from the left.

Following Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939, Britain declared war on Sunday 3rd September. For a few weeks, Western Europe was eerily quiet during the ‘phoney war’. Preparations for war continued in earnest, but there were few signs of conflict, and civilians who had been evacuated from London in the first months drifted back into the city. Gas masks were distributed, and everybody waited for the proper war to begin.

Auxiliary Air Force, Stanmore 1939. Bob is third from left in the second row.

Auxiliary Air Force, Stanmore 1939. Bob is third from left in the second row.

Destination Fife

Rumours that volunteers were sought for barrage balloon postings to unspecified destinations crystalized to reality in mid-October when a large company of volunteers were assembled at Chigwell in Essex. From there they were dispatched to various sites – in Bob’s case by train to Inverkeithing where he was one of 115 other ranks, a Flying Officer and a Flight Lieutenant who was Commanding Officer of ‘B’ Flight, 948 Squadron, RAF, with responsibility for operating nine barrage balloon sites around the North Queensferry area.

The proper war had begun with a bang in the Forth on 15th October 1939 when German planes attacked naval ships in the First Air Raid of WWII

948 squadron arrived on 25th October 1939, a mere nine days after the raid. Whether their arrival was a reaction to the raid, or un untimely planned arrival is unknown, but a barrage balloon flight had already been transferred from Glasgow to protect Edinburgh on 17th October.

The Squadron comprised 4 Flights – A, B, C & D – with responsibility for barrage balloons on the north shore of the Forth from Rosyth Dockyard to Methil. [No. 948 Balloon Squadron RAF is listed as having 24 balloons in Aug 1940.]

‘B’ Flight’s mission was to protect area round the north end of the Forth Bridge.

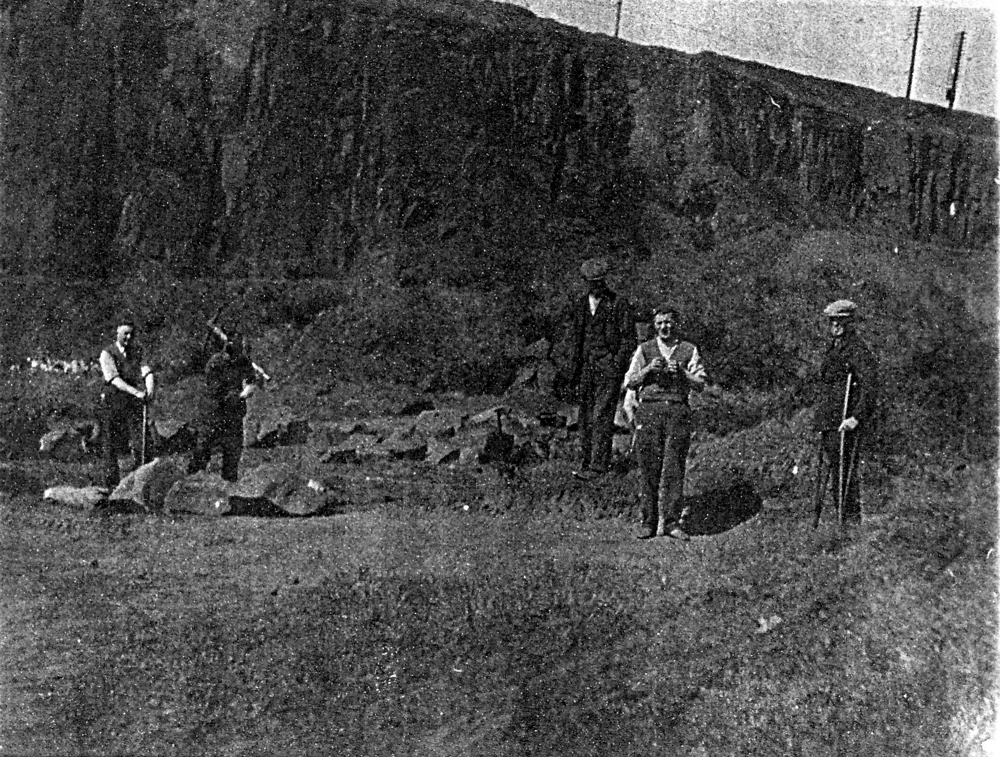

Within 4 days balloon beds had been constructed, winches were in place and balloons were flying at each of the nine sites. Each site was manned by a crew of a corporal and eight or nine airmen.

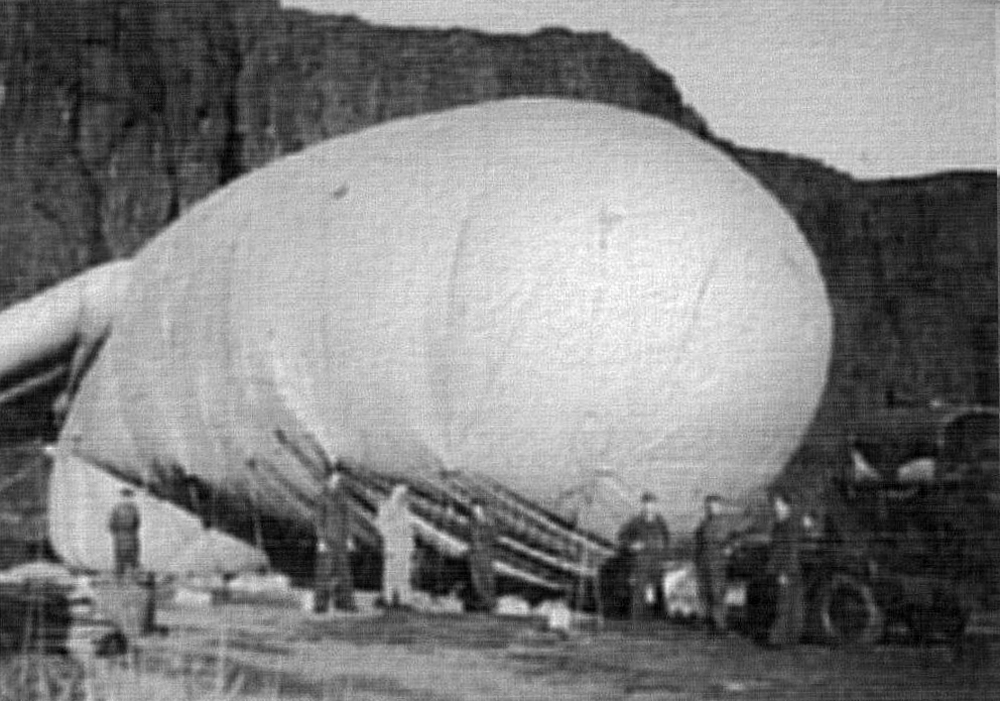

Late October 1939. Preparing balloon bed at Carlingnose Quarry.

Late October 1939. Preparing balloon bed at Carlingnose Quarry.

Villagers Paddy McGinty and John Picthall (on crutches) look on.

‘B’ Flight HQ Staff occupied Sycamore Bank, Ferryhills Road, North Queensferry, where a box room was set up as a telephone switchboard, and other rooms became the Orderly Room and Meeting Room. Squadron HQ was at Park Road School in Rosyth.

The nine sites were:

8 Castlandhill Road

9 Spencerfield (a)

10 Spencerfield (b)

11 Preston Crescent

12 Tilbury Quarry

13 Ferryhills Golf Club

14 Welldean

15 Carlingnose Quarry

16 Ferrybarns

Balloon flying at Site 16 (Ferrybarns)

Balloon flying at Site 16 (Ferrybarns)

From an RAF Christmas Card 1939.

Sites from Rosyth to Inverkeithing

This map shows further barrage balloon sites identified by Canmore at Rosyth, North Queensferry and Inverkeithing.

The ‘B’ Flight locations from Bob’s map are red, the additional seven sites round Rosyth are blue, headquarter locations are purple. Of the four sites in green from Canmore, the three at Inverkeithing may be later positions for the sites on Bob’s map. The location of the site at Carlingnose is identified by Canmore as Carlingnose Barracks Barrage Balloon Site.

Given the military’s predilection for orderly numbering systems, these seven were probably the responsibility of ‘A’ Flight. (1) Windylaw Head, (2) Brankholm Brae, (3) Hilton Road, (4) Dundas Road, (5) Ferrytoll Road, (6) Castle Road, and (7) Rosyth Recreation Ground.

[No. 948 Balloon Squadron RAF is listed as having 24 balloons in Aug 1940. So ‘C’ and ‘D’ Flights were probably smaller units, with eight further balloons covering the stretch from RNAS Donibristle to Methil.]

Crew accommodation

The balloon crews were accommodated wherever was available – church hall, loft, barn or stable – until purpose-built timber buildings arrived after several months.

Sites 9 and 10 were accommodated in outbuildings at Spencerfield farm.

The site 11 crew had an outhouse and tent in Preston Crescent, Inverkeithing.

Winter 1939/40 at Spencerfield. Tented accommodation to right.

Winter 1939/40 at Spencerfield. Tented accommodation to right.

Site 12 at Tilbury Quarry were originally squeezed into an outbuilding – possibly the explosives shed until they were allocated a section of the office building.

Site 13 were housed in the Golf Club House.

Site 14 used an Admiralty shed until they moved to the dredging office at Welldean

Site 15 were billeted in the old church hall at the foot of The Brae.

Site 16 first occupied a loft in The Hope then soon moved to more comfortable quarters in an outhouse at Ferrycraig by Ferrybarns.

Site 8 was originally near St David’s but the site proved to be unsuitable – possibly because it was in the line of take-off from RNAS Donibristle. The site was relocated to Seggburn off Castlandhill Road. This explains why it is out of sequence with the other sites which were numbered by location!

The overall command structure ran from Balloon Command – responsible for overall strategy – to Balloon Centres. In this case Balloon Centre No 19, which was responsible for hydrogen gas supplies, equipment replacement and command of two squadrons – 929 and 948 each with their own commanding officer.

948 squadron HQ was at Park Road School, Rosyth, and control then passed through Flight HQ to the individual site crews.

Each site crew bore responsibility for the functional efficiency of its balloon, winch and the winch-bearing vehicle.

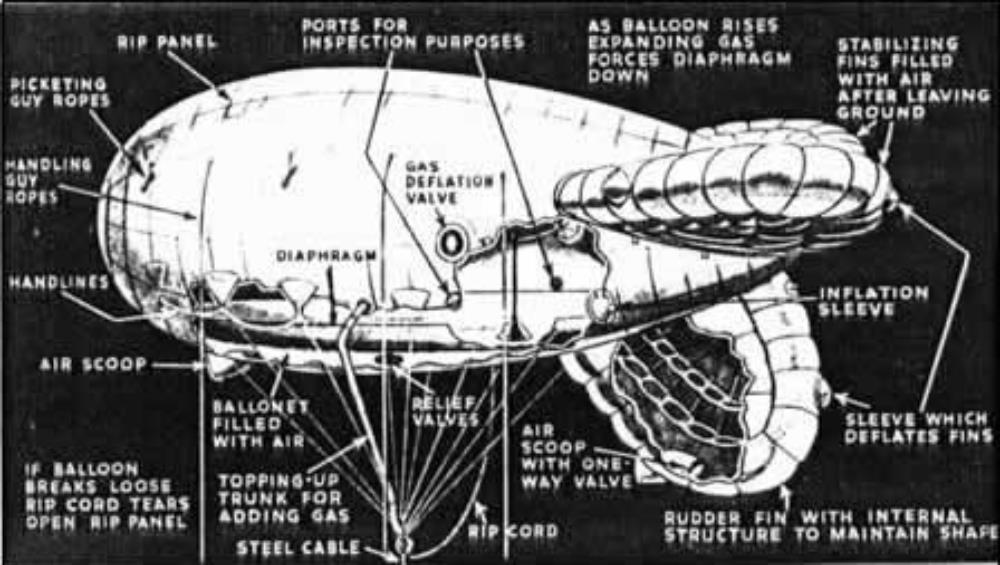

A Barrage Balloon

Each balloon was 66 ft [20 m] long and held nearly 20,000 cu ft [1860 cu m] of hydrogen gas. It flew at heights of up to 4,500 ft [1380 m] on the end of steel restraining cable.

Diagram showing various parts of a balloon

Diagram showing various parts of a balloon

The curtain of balloons prevented enemy aircraft from dive-bombing targets from a low level forcing them to operate with less accuracy at higher altitudes. [The raiders on 16th October crossed the North Sea at 23,000 feet, then dropped to 12,000 feet as they approached their targets. They then dived, releasing their bombs at 1,800 feet and levelling off at 900 ft. This would have been a very dangerous manoeuvre inside a defensive balloon curtain of sturdy steel cables topped with highly inflammable hydrogen gas!]

Danger to operators

There were also dangers for the balloon crew. Shrapnel, yawing, mechanical failure, defective cable, fabric porosity, human error, human culpability and the elements displaying their natural waywardness all tended to make service life a series of unpredictable events.

One could never claim, with any confidence, to understand the motivation of the amply-proportioned prima donnas.

26th November 1939 was a windy day which brought several problems.

00:33 hours: Site 11 (Preston Crescent) LZC 2073 had two of its ton patches torn off in the gale. Deflated.

02:10 hours: Site 16 (Ferrybarns) LZC 1447 had ton patch torn off. Balloon torn in half during subsequent deflation.

02:30 hours: Site 10 (Spencerfield) LZC 1595 damaged and torn in gale. Severely damaged during deflation.

02:38 hours: Site 13 (Ferryhills) LZC 2040 ripped: ton patches strained; Bakelite valve broken; balloon deflated.

02:50 hours: Sites 15 (Carlingnose Quarry) LZC 2026 ton patches torn; balloon deflated.

(A ton patch is where the guy lines are attached to the balloon and are so named because they had a breaking strain of one ton (1000kg))

Sites 8 (Castlandhill Road) and 14 (Welldean) had already ceased to be operational following similar weather conditions four days previously.

On 29th November 1939, balloon LZ 345 at Spencerfield went out of control at 2,500 feet. Breaking free, it went off trailing 1,000 feet of steel cable and entered Donibristle air space. It there tangled with an operational balloon on ‘C’ Flight’s site 7, which in turn broke loose. Both balloons then headed off in a north-easterly direction.

On May 15th 1940, an unexpected thunderstorm caused the balloons at Carlingnose Quarry and Ferrybarns to burst into flames. The Ferrybarns balloon with 90 feet of steel cable heeled across power lines but had little effect on public services. However the Carlingnose balloon trailing 500 feet of cable fell across a passenger train travelling along the northern approach of the Forth Bridge to North Queensferry station. The burning fabric of the balloon was dragged onto the roof of the rear carriage, which began to burn. Fortunately there was only superficial damage to the coach and none of the passengers experienced any ill effects.

On 7th February 1941, seven balloons broke away at varying heights in the course of a gale gusting to 85 mph. At site 15 (Carlingnose Quarry) the balloon with 2,000 feet of cable attached dragged the winch vehicle to the cliff edge and dropped it onto the stony beach 75 feet below. The winch driver leapt clear seconds before the plunge.

Site 8 (Seggburn). High winds lifted the winch-truck to the edge of the field.

Site 8 (Seggburn). High winds lifted the winch-truck to the edge of the field.

The balloon is deflating in the trees top right (out of shot).

Improved practices

By 1941, a great deal of sophistication in ballooning had arrived. Rapid deflation could be brought about by manipulating a special patch, and could even be achieved under crash conditions by an explosive rip link. Detonator links allowed the steel cable to parachute to the ground in the event of a breakaway. Coal gas was provided to many sites to facilitate topping up and to economise on the consumption of hydrogen. [Coal gas is a mixture of hydrogen and highly-toxic carbon monoxide, it was the standard domestic fuel supply until it was replaced by the safer “natural gas” which consists of methane.]

When a balloon was not being flown it was now secured to concrete embedded rings, which replaced the earlier screw pickets. These were arranged on a 90 foot all-directional balloon bed.

Retaining rings at Carlingnose Quarry

The Barrage Balloon site at Carlingnose Quarry is the only site in the village known to retain its balloon anchor rings.

A set of rings

A set of rings

The lead anchor point

The lead anchor point

The lead anchor point and sets of rings

The lead anchor point and sets of rings

These red markers show the position of the lead anchor and sets of retaining rings.

These red markers show the position of the lead anchor and sets of retaining rings.

This photograph shows the restraining cables attached to the various rings, as wells a the “flying cable” from the winch truck.

This photograph shows the restraining cables attached to the various rings, as wells a the “flying cable” from the winch truck.

1941 – arrival of the first Polish airmen

By mid-1941, sites 13 (Ferryhills Golf Club), 14 (Welldean) and 15 (Carlingnose) were managed by Polish airmen, who had escaped from Poland and made their way across Europe to the UK.

September 1941 – Flight HQ moves to Donibristle

On 13th September 1941, the occupation of Sycamore Bank as ‘B’ Flight HQ came to an end when ‘B’ and ‘C’ Flights merged with control now centred in the north-west wing of Donibristle House. Flight cookhouse and dining hall were sited in the stables a few hundred yards away in the direction of St Bridget’s Church. The billet and sleeping quarters for HQ airmen below NCO ranks was the upper floor of a drab stone building midway between the house and the stables. Twenty three iron bedsteads lined the front rear and north walls. There were no toilet or washing facilities. The floor was gnarled timber laid-on boards (i.e. not tongue and groove jointed) which let through the sounds and smells of the horses which occupied the lower floor. It carried graffiti from being used in WWI when it was named as “Pneumonia Hall.”

1942 – Mergers and transfers

On 15th May 1942, after a long period of rationalization involving Flight mergers and site closures, 948 Squadron was abolished and the sites and crews were absorbed into 929 Squadron. The latter unit was the other half of 19 balloon centre and comprised land sites at the Lothian side of the Forth, and barge sites on the river. The whole constituted the Forth barrage.

On 20th and 21st July 1942, almost all of the British personnel in 929 Squadron were transferred to 945 Squadron in Glasgow. They were replaced with Polish personnel from 945 squadron, making 929 an all-Polish squadron with Bob as liaison officer.

This lasted until November 1942 when Bob was granted a request to transfer to ‘B’ Flight 929 Squadron at Forth View House Dalmeny.

The arrival of the WAAF

When plans for the Barrage Balloon system were formulate pre-war, it was intended to be manned by members of the Auxiliary Air Force – the factory, bank, local government and office workers who trained at weekends. However, inadequate preparation time and unexpected expansion of activities meant that a large number of regular airmen, especially NCOs, were pinned down to balloon crew activity.

The emergence of Volunteer Reserves who chose to join the RAF without compulsory call-up alleviated some of the pressure. Early in 1941, the Secretary of State for Air suggested that WAAF (Womens Auxiliary Air Force) personnel might take over the entire balloon flying operation.

The matter was investigated and after a set of volunteer fabric workers had been trained and tested on balloon handling tasks under adverse weather conditions, the scene was set for the gradual take-over of a large proportion of the nation’s balloon barrage defences.

10,000 airmen were removed from balloon sites to be replaced by 15,700 WAAF balloon operators.

The Luftwaffe changes tactics

After the air raid on the Forth in October 1939, things were relatively quiet until the heavy air raids of the Battle of Britain from 10 July until 31 October 1940, and the Blitz from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941.

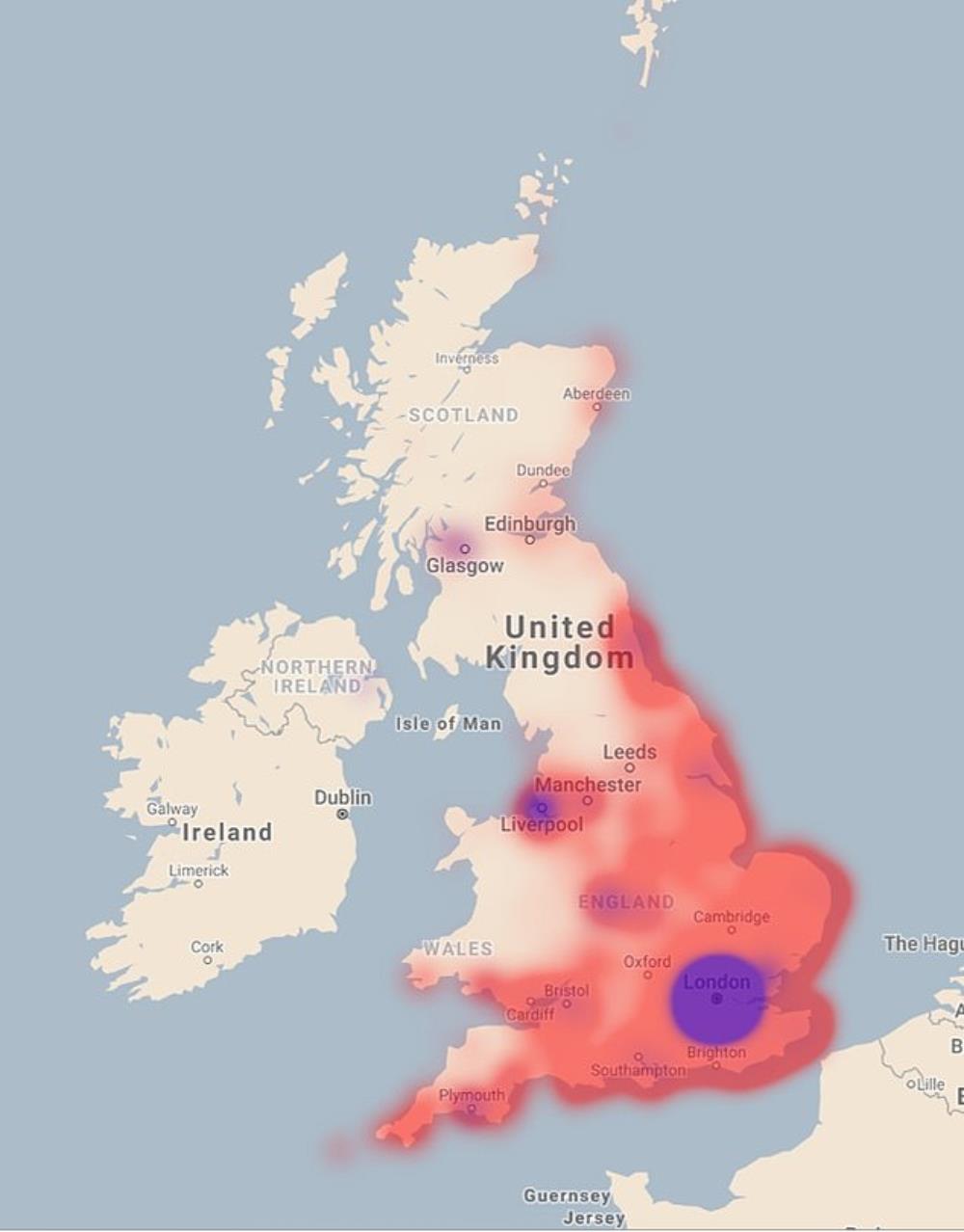

“Heat map” showing the frequency of air raids during WWII

“Heat map” showing the frequency of air raids during WWII

Data from daily reports complied during the war revealed that London and the south-east were the worst hit, but the Luftwaffe bombers made it much further across the west and north of the UK than some realise (purple shows the most intense levels of bombing while the red indicates there were numerous attacks in that area)

Heavy raids continued during 1942, but by 1943 hit and run raids with relatively few aircraft became more common.

The Bombing Britain website gives more information.

Click on “Essay” for an article about this topics

Click on “Data” to download an Excel spreadsheet which details every air raid.

Preparations for D-Day

In late 1943 and early 1944, volunteers were sought to operate barrage balloons in the southern counties of England to create a barrage curtain round the war-supply assembly points that would eventually service the Normandy landings on D-Day. Bob volunteered and was transferred to Kent.

Barrage balloons over the hills of Surrey 1944

Barrage balloons over the hills of Surrey 1944

These barrages also acted as a defence against low-flying V-1 doodle-bug flying bombs which were launched daily in the summer of 1944.

Barrage balloons were also deployed on the Normandy beaches during the invasion of Europe.

Barrage balloons were also deployed on the Normandy beaches during the invasion of Europe.

By September 1944, the Germans had lost the battle to hold on to Normandy; France was well-nigh liberated and the push towards the east continued.

On 8th September 1944 Battersea Power Station was blown up by the arrival of the first of Hitler’s latest unmanned war device – the V2 ballistic missile. This immediately outmoded the barrage balloon resulting in the redeployment of many personnel to other branches of the RAF – in Bob’s case RAF Transport Command.

In 1945, when the R.A.F. balloon command was disbanded, there were over 3,000 balloons in service with over 33,000 men and women serving.

Memorial to the men and women of RAF Balloon Command

the memorial website

The Memorial is in the RAF Association Memorial Garden, near the Armed Forces memorial in the

National Memorial Arboretum

Croxall Road

Alrewas

Lichfield

Staffordshire

DE13 7AR

England

Description

Polished blue-black granite rectangular stone with a sloping front face. A panel is fixed to the front face enclosing a drawing depicting the launch of a balloon. The stone has commemorations engraved in gold lettering on each side and below the panel. The stone is placed in the Royal Air Forces Association Remembrance Garden.

Inscription

[Front face]:

In memory of the men and women who served

with the balloon barrage squadrons

of RAF balloon command defending this country

and vital areas abroad during the Second World War.

Erected in 2015 by the balloon barrage reunion club B.B.R.C.

[3 o’clock face]:

R.A.F. Balloon Command was established in 1938

to provide additional air defence

of important targets and cities in Great Britain.

During the second world war, by 1940,

there were over 1,400 barrage balloons in service.

By December 1942, some 10,000 men had been

released for other duties and replaced by over

15,000 W.A.A.F. balloon operators.

In 1945, when the R.A.F. balloon command was disbanded,

there were over 3,000 balloons in service

with over 33,000 men and women serving.

[9 o’clock face]:

The purpose of the balloon barrage

was to prevent accurate bombing by

forcing enemy aircraft to fly at higher altitude.

This was achieved by steel cables held up by the balloons

flown up to 5,000 ft height. Aircraft which flew into the cables

could be seriously damaged or brought down.

The barrage balloons, filled with hydrogen gas,

were flown either from fixed or mobile winches

each operated by 10 men or 14 women, with two NCOs.

The Forth Balloon Barrage on Film

The Imperial War Museum website holds parts 1 and 2 of the movie Squadron 992, the first being training in the basics of Barrage Balloon hardware at various UK sites. The second shows deployment to sites and launching, mostly at South and North Queensferry to protect the bridge.

The film also shows a reconstruction of the The First Air Raid of WWII. The sequence comparing a hare being chased by dogs with the pursuit of a German bomber by Spitfires echoes the words of Stoep – one of the German bomber pilots – recalling the moment when Spitfires came within range and began their pursuit of his Ju88: “Ten to twelve Spitfires were after me. I resemble a hare, shot and wounded, but still chased.”

top of page