Carlingnose Airstation

Carlingnose Naval Air Station 1912 to 1914

The beach at Port Laing was the site of the first Naval Air Station in Scotland and the genesis of the Royal Navy Air Service.

Early Aviation

When the Carlingnose Airstation was established in 1912, aviation was very much in its infancy, and everyone involved was a pioneer.

The first ever heavier than air powered flight had taken place a mere nine years earlier. . .

December 17th 1903 – First heavier-than-air powered flight. 37 metres

On December 17th 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, sustained, powered heavier-than-air flight, on a beach four miles south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. That flight lasted 12 seconds, and covered 37 metres. The fourth flight later that day covered 260 metres in 59 seconds.

The first British heavier than air flight had taken place only four years earlier . . .

October 16th 1908 – First British heavier-than-air powered flight. 464 metres.

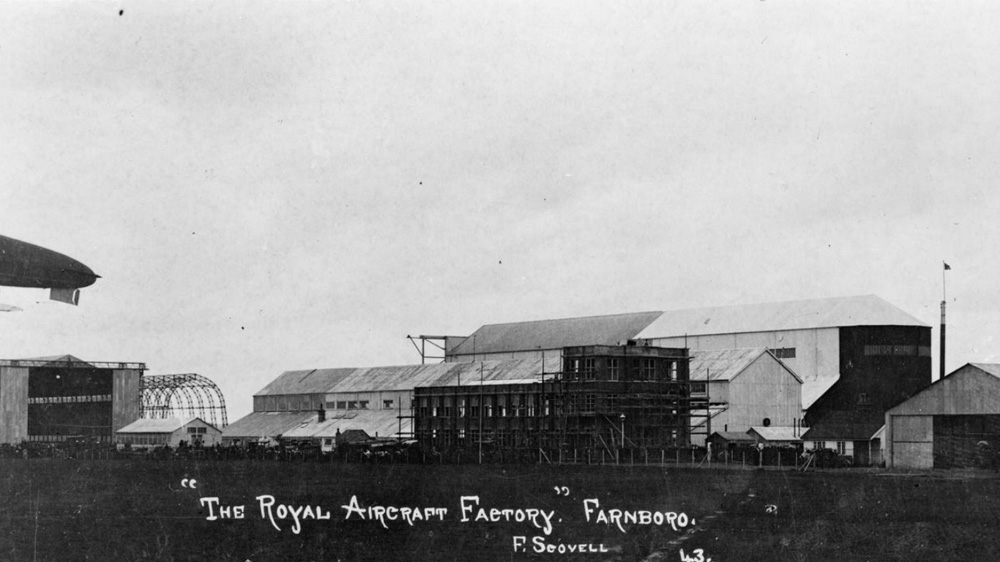

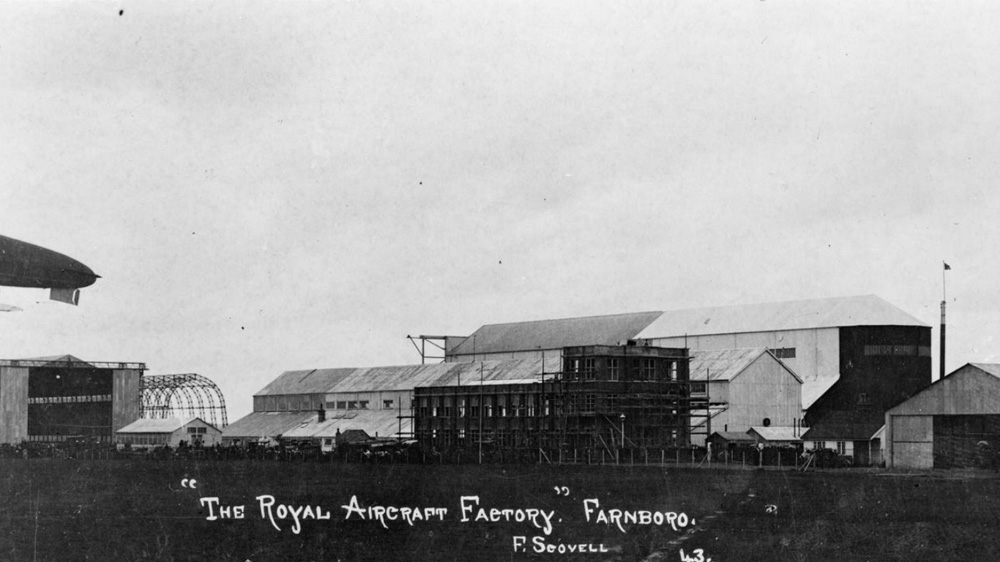

On October 16th 1908, Samuel Franklin Copy made the first sustained aeroplane flight in Britain, at Laffans Plain, Farnborough. He built his own plane in 1907 at the Army Balloon factory in Farnborough – “The British Army Aeroplane No 1” or “Cody 1.” The flight was of 464 metres, and ended in a crash – a wingtip touched the ground as Cody attempted to turn and avoid a tree.

And the first long-distance flight only three years earlier.

July 25th 1909 – First heavier-than-air powered flight across the English Channel 22 miles – 36 km

On July 25th 1909, Louis Bleriot made the first powered flight across the English Channel, from Calais to Dover. The flight lasted 36 minutes and 30 seconds.

Although the range of a flight had now been extended, manoeuvring was still a major issue.

Even turning an aeroplane was a very difficult exercise. Bleriot crash landed at Dover.

The Birth of British Naval Aviation

In 1908, the British government recognised that the use of aircraft for military and naval purposes should be investigated.

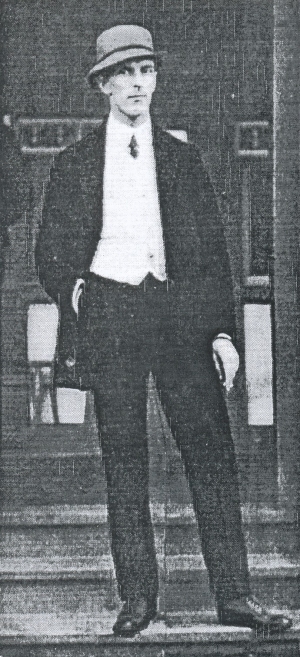

On 21 June 1910, Lt. George Cyril Colmore became the first qualified pilot in the Royal Navy, after paying for training out of his own pocket.

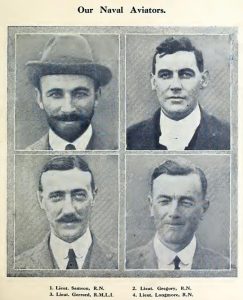

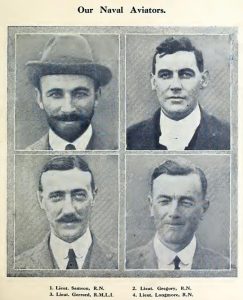

In November 1910, the Royal Aero Club, offered the Royal Navy two aircraft with which to train its first pilots. The Club also offered its members as instructors and the use of its airfield at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey. The airfield became the Naval Flying School, Eastchurch. Two hundred applications were received, and four were accepted:

Lieutenant C. R. Samson,

Lieutenant A. M. Longmore,

Lieutenant A. Gregory and

Captain E. L. Gerrard, RMLI. [Royal Marine Light Infantry]

These four pilots were the genesis of what became the Royal Navy Air Service and later the Fleet Air Arm.

A (Very) Short History of British Naval Aviation

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was constituted by Royal Warrant on 13 April 1912. It consisted of two wings: the Military Wing making up the Army element and Naval Wing, under Commander C. R. Samson.

On 1 July 1914, the Naval Wing became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

By the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the RNAS had 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons and 727 personnel. The Navy maintained twelve airship stations around the coast of Britain from Longside, Aberdeenshire in the northeast to Anglesey in the west. The RFC had several hundred airfields around the country.

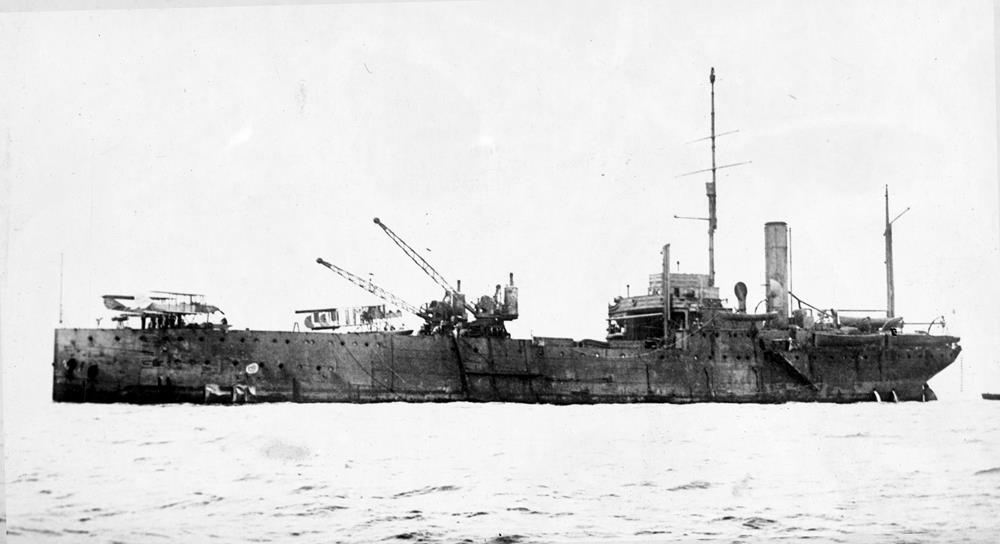

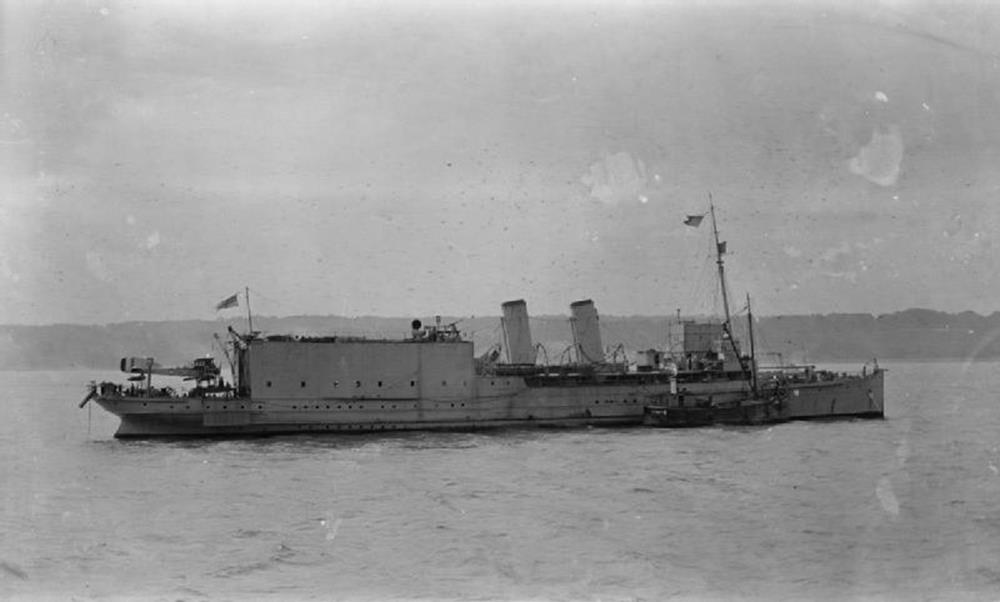

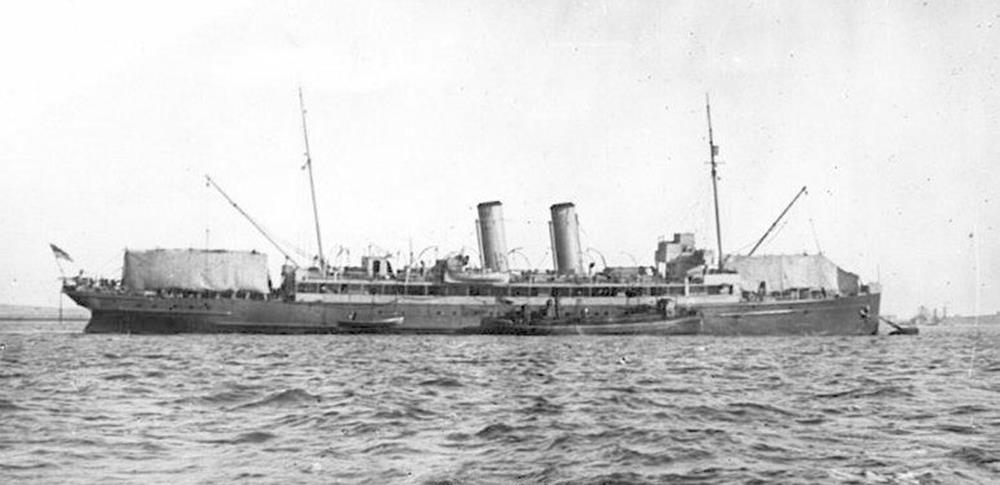

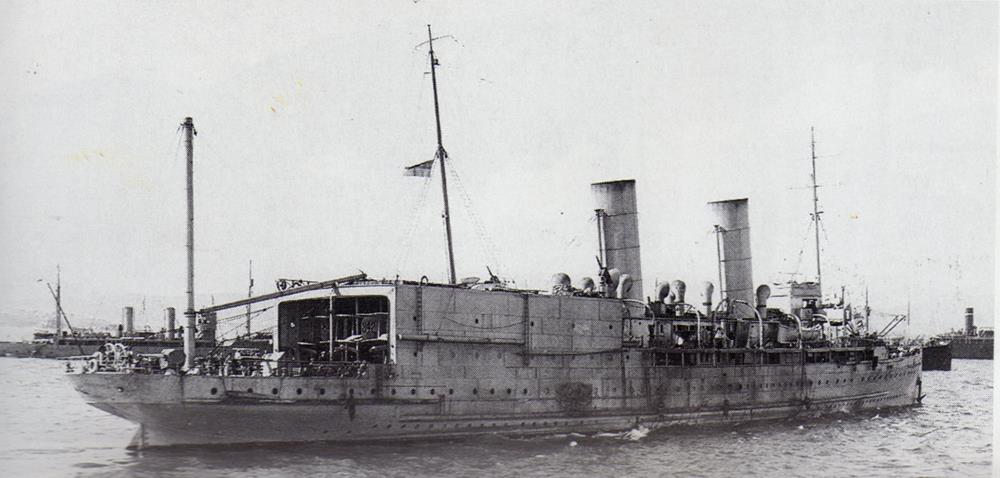

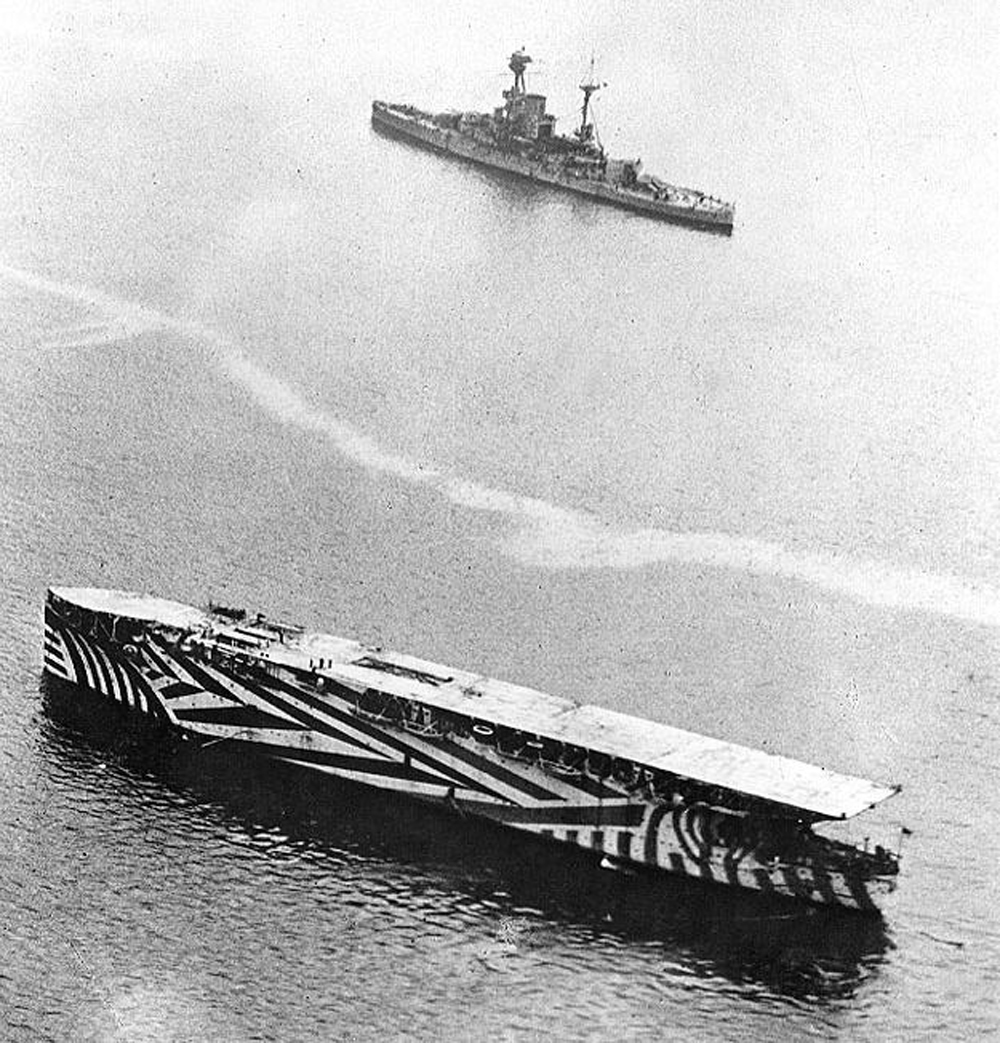

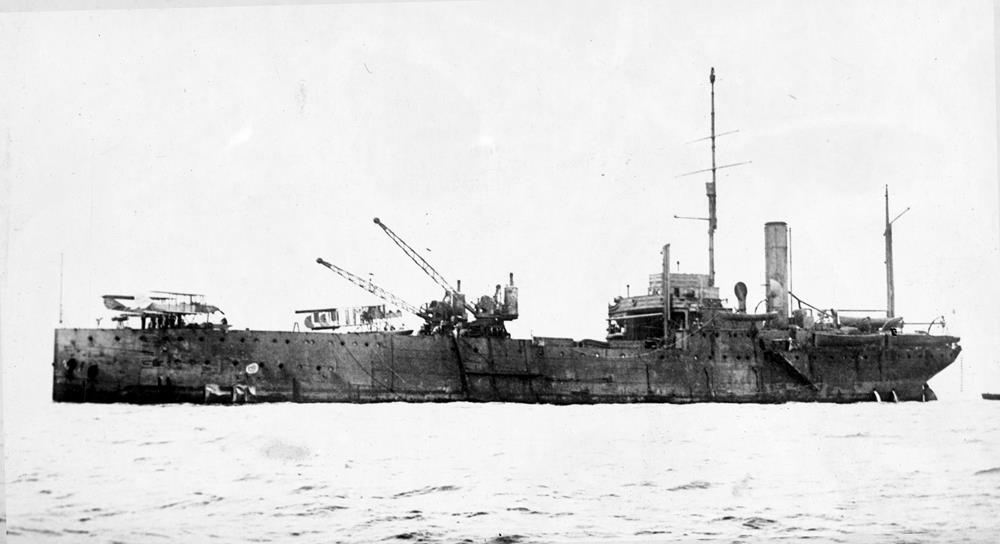

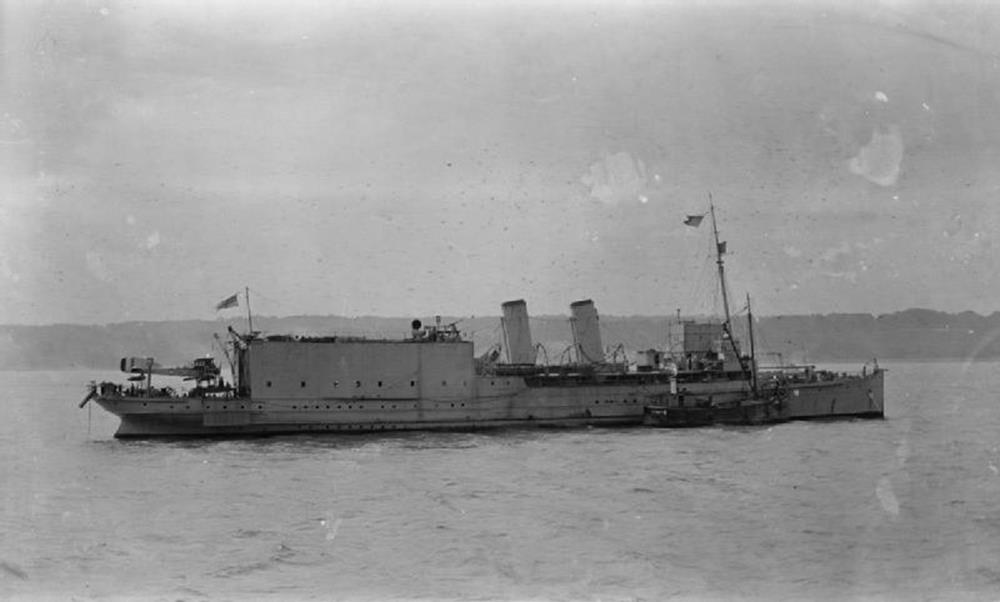

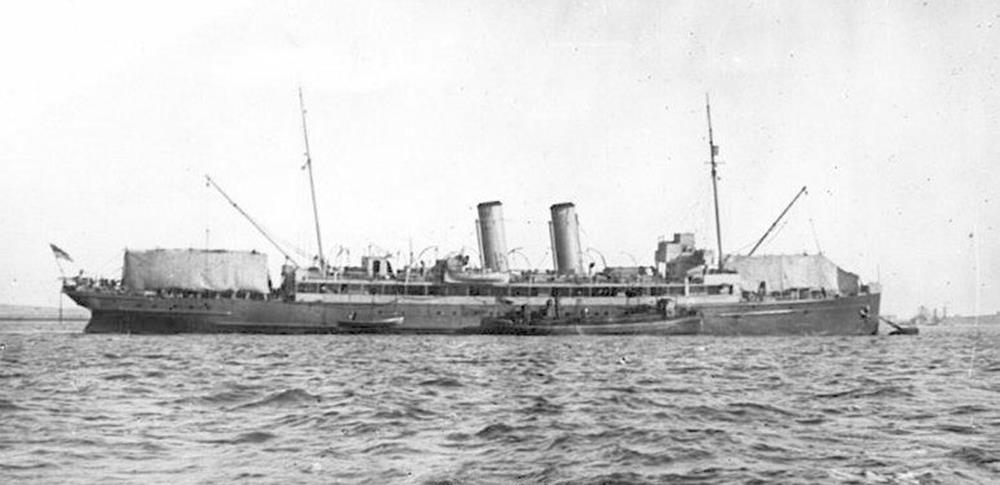

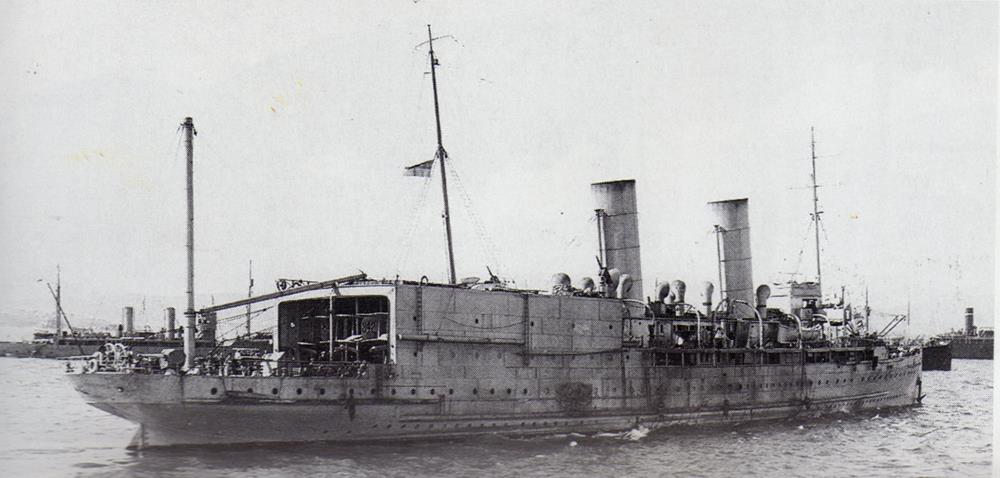

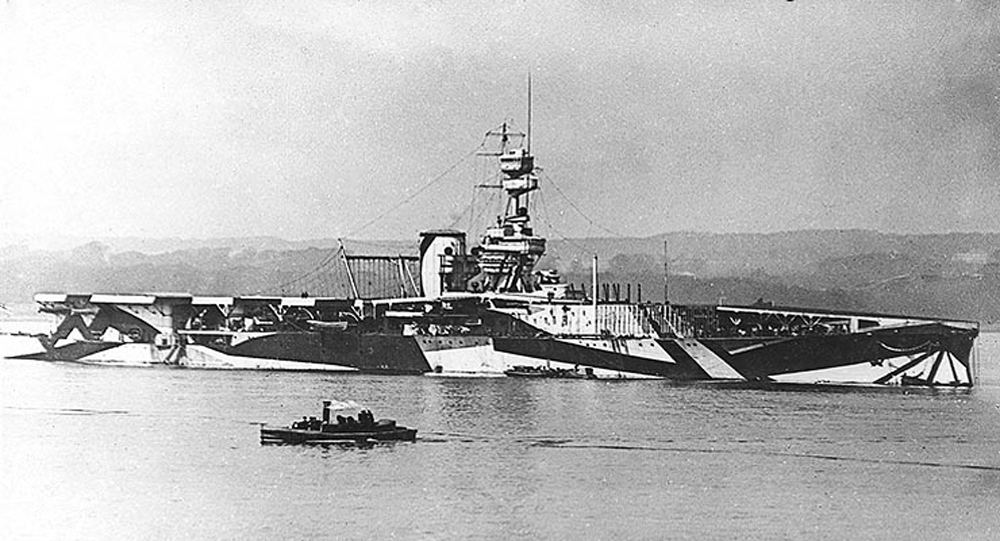

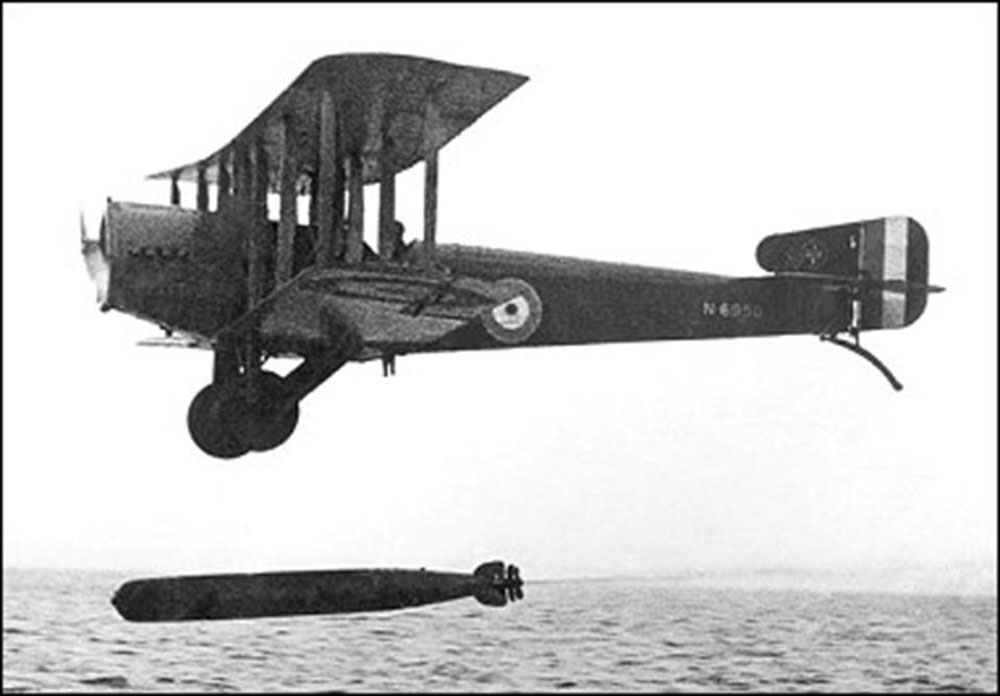

Before techniques were developed for taking off and landing on ships, the RNAS had to use seaplanes in order to operate at sea. Beginning with experiments on the old cruiser HMS Hermes, special seaplane tenders were developed to support these aircraft. It was from these ships that a raid on Zeppelin bases at Cuxhaven, Nordholz Airbase and Wilhelmshaven was launched on Christmas Day of 1914. This was the first attack by British ship-borne aircraft.

On 1 August 1915 the Royal Naval Air Service officially came under the control of the Royal Navy.

On 1 April 1918, the RNAS was merged with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) to form the Royal Air Force.

At the time of the merger, the Navy’s air service had 55,066 officers and men, 2,949 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 coastal stations.

The RNAS squadrons became the Fleet Air Arm of the new structure, individual squadrons receiving new squadron numbers by effectively adding 200 to the number so No. 1 Squadron RNAS (a famous fighter squadron) became No. 201 Squadron RAF.

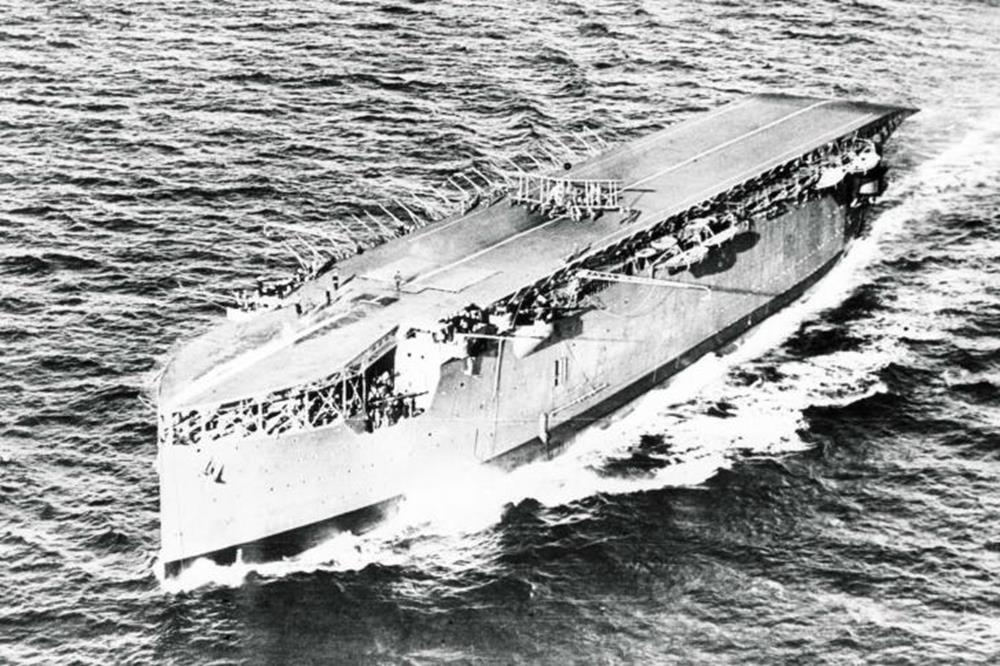

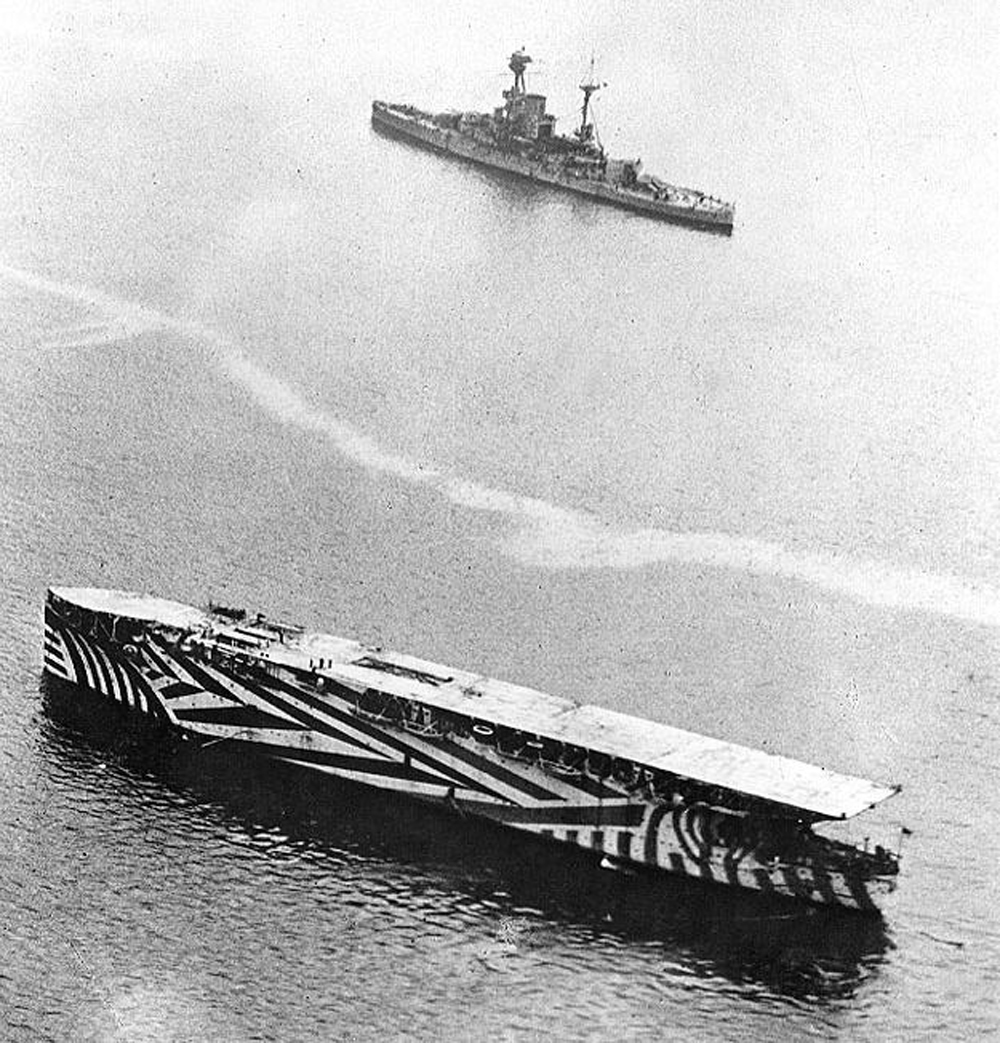

The Royal Navy regained its own air service in 1937, when the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Air Force (covering carrier borne aircraft, but not the seaplanes and maritime reconnaissance aircraft of Coastal Command) was returned to Admiralty control and renamed the Naval Air Branch. In 1952, the service returned to its pre-1937 name of the Fleet Air Arm.

First Flight across the Forth

Not long after the naval aviators had gained their “wings”, a Scottish aviator made the first flight across the River Forth.

September 7, 1911 – First heavier-than-air powered flight across the Forth. 28 miles – 45 km

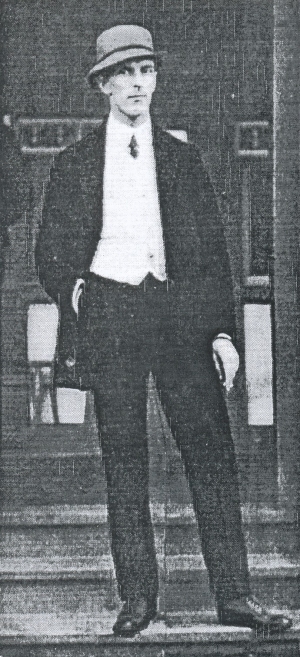

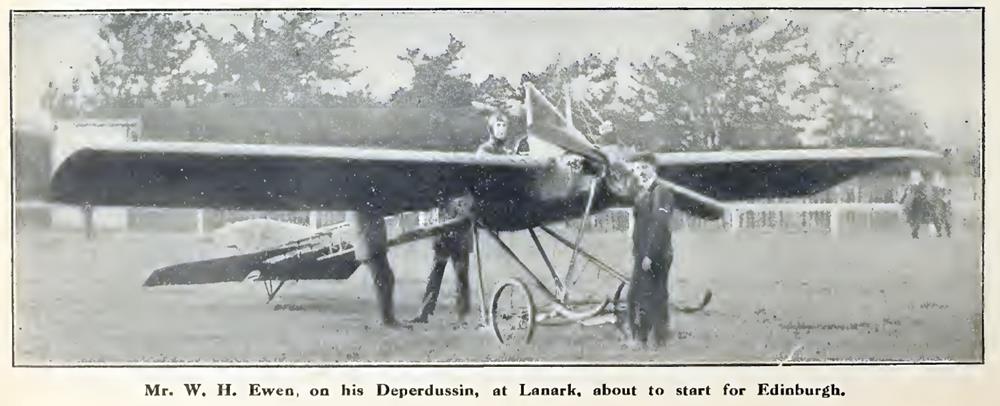

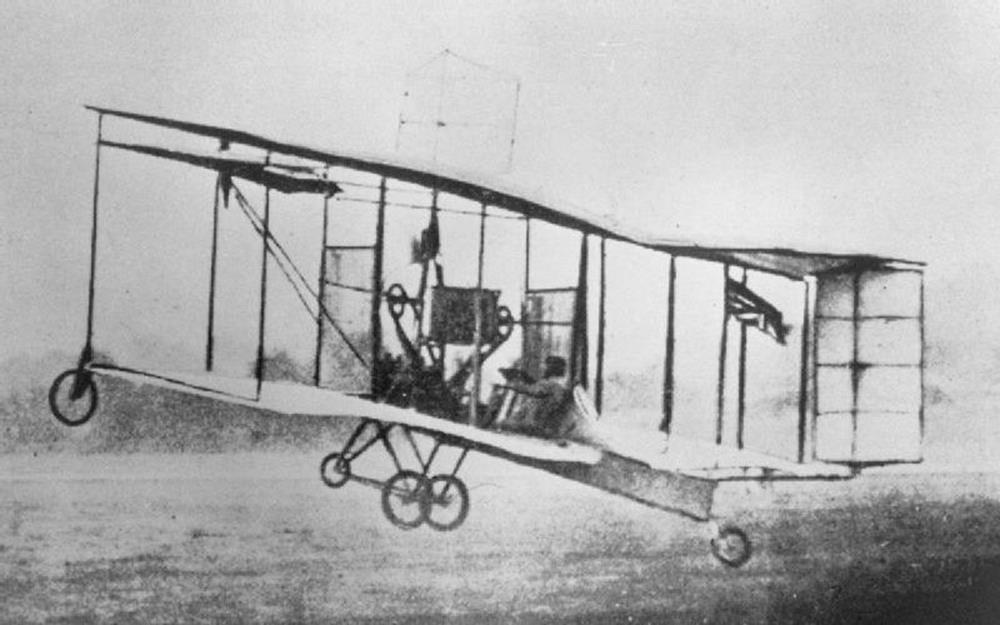

W. H. Ewen, the Scottish aviator, on Wednesday, August 30th, flew from the Marine Gardens, Portobello, near Edinburgh, across the Firth of Forth, and back again to the Gardens. At about 300 feet, he made for Kinghorn, leaving Inchkeith on his right. He appeared to find the wind troublesome at this altitude, and rose again till he was about 1,000 feet up. Past Inchkeith, Ewen found himself in an almost dead calm, and held on till about a mile from Kinghorn, where he turned up the Firth towards Leith.

Two miles from the Port he again turned and came back to the Marine Park. The crowd had greatly increased, and as the aviator appeared he was loudly cheered. He descended, but seeing he could not land in such a restricted area he went over the heads of the crowd and landed in a field about a mile to the west. There he had the planes taken off and the machine wheeled back to the enclosure.

On his return to the Park, Ewen had a most enthusiastic reception. “See the Conquering Hero Comes” was played, by the band of the 3rd Dragoon Guards, and Councillor Rawson, on behalf of the Executive, met him at the Members’ Club and congratulated him on his success. A speech was called for, and in a few words he expressed his pleasure with, the manner in which his flight had been received. He was glad that a Scotsman had been able to do something. His mother and father witnessed his flight.

Ewen is a graduate of Edinburgh University, and is organist at Park Parish Church, Glasgow. He only took up aviation this year, but he made remarkable progress at Hendon. He flew at his first attempt, and gained his pilot’s certificate at his third flight. This is a record for Hendon.

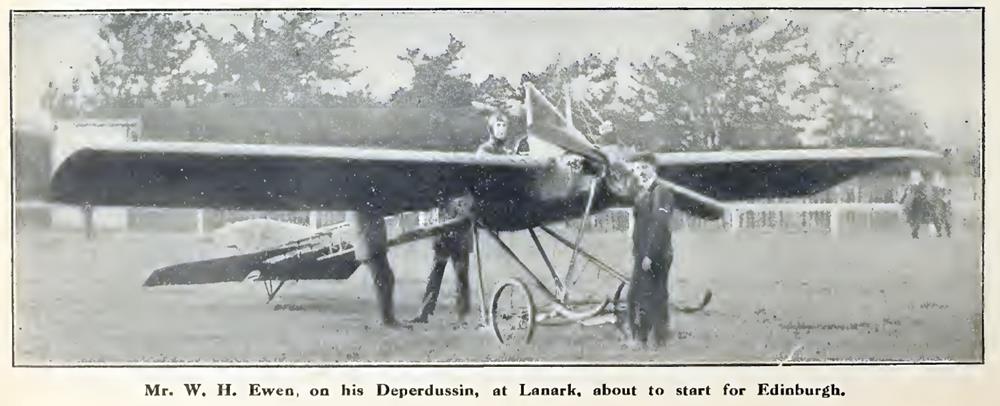

Writing to The Aeroplane in answer to a letter, Mr. Ewen says: “This, I believe, is really the longest distance [about 28 miles.— Ed.] attempted over water with such a low hp (28-32 Anzani) since Bleriot crossed the Channel. The machine was delivered to me in a hurry, and had not been previously flown. I had no chance for trial flights, and only had 150 yards to rise in and clear a fence of 15 feet. I am pleased, however, with the way in which the Deperdussin flies and handles. I am being presented with a large silver cup by the Edinburgh Marine Gardens in honour of the event.”

“I am soon taking the machine back to Lanark, where I expect to put at least two pupils through during the next week for R.Ae.C. certificates. I have two splendid mechanics in the school looking after things, that I may be thoroughly up to date, one of them, Mr. Warren, from the Hendon Aerodrome, being responsible for the splendid running of my engine on Wednesday.”

In the morning, by way of practice, Ewen had done a mile cross-country flight. Shortly after six a.m. he started from the sports enclosure, after a run of about 150 feet, and steered, seawards towards Leith. Circling round by Seafield, Ewen passed over the golf course at Craigentinny and turned inland, to Duddingston and Joppa. His intention was to fly back to the Marine Park, but near the golf course at Portobello the wind became troublesome, and he was obliged to descend on Northfield Farm. At one point he rose to 700 feet, but his average altitude during the flight was about 350 feet.

It is to be hoped that after so fine a performance aviation, will become popular in Scotland, and that the Lanark Aerodrome will find plenty of pupils.

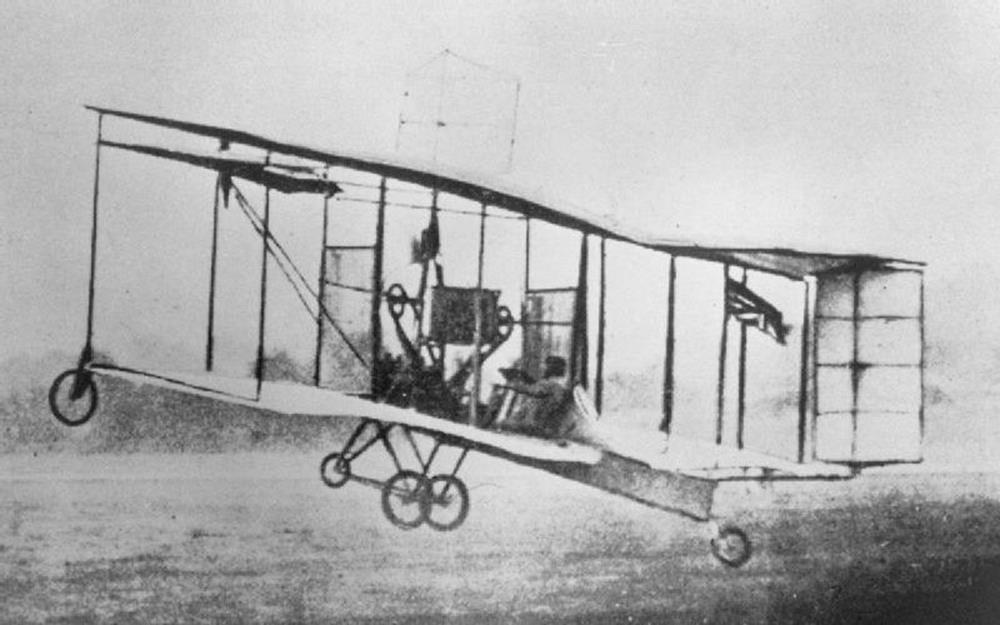

Ewen’s Deperdussin Monoplane at Lanark, 1911

Ewen’s flight over the Forth demonstrated that aircraft had become much more manoeuvrable, he was able to fly across the river turn, fly downstream turn back and then circle to identify a suitable landing field.

The Royal Aircraft Factory

Meantime the Government had created the Royal Aircraft Factory to design and produce planes for the Army and Navy. This venture was met with much scepticism and even hostility from some, quarters who believed that it would be better to trust in competition between private companies to speed development.

The “Aeroplane” magazine was very much in this camp.

In June 1911, The Minister of War announced that the Air Battalion possessed ten aeroplanes.

“Aeroplane” responded:

Ten little aeroplanes on paper look so fine,

One is an ancient Wright, and so there are nine.

Nine little aeroplanes, somewhat up-to-date,

The “Type XII.” B1eriot really makes eight.

Eight little aeroplanes, rather less or more,

Half ain’t delivered yet, and so there are four.

Four little aeroplanes, on the’ ground so free,

Someone tried the Farman, and then there were three.

Three little aeroplanes, on the ground to view,

Up went the de Havilland, and then there were two.

Two little aeroplanes, Paulhan’s “’bus” was fun!

But when it came to landing it — then there was one.

One little aeroplane, engine over-run,

Playing on the test-bench, and then there was none.

First Navy Pilots

Aeroplane magazine – October 19, 1911 – Naval Aviation.

Within the last few days a most significant step has been taken. The four officers mentioned above have been sent by the Admiralty to make a tour of the Continental aerodromes, so as to learn at first-hand what is being done by the leaders of aeroplane fashions. They have been recently to Reims, where they have had the opportunity of witnessing the progress of the great French military trials, in which the latest products of the leading French manufacturers are being tested under most searching conditions prior to the distribution of orders amounting to about £100,000 by the French War Office. It is only to be hoped that the knowledge gained in this tour will enable these officers to persuade the Admiralty, now they have returned, to take up aeroplanes on an adequate scale.

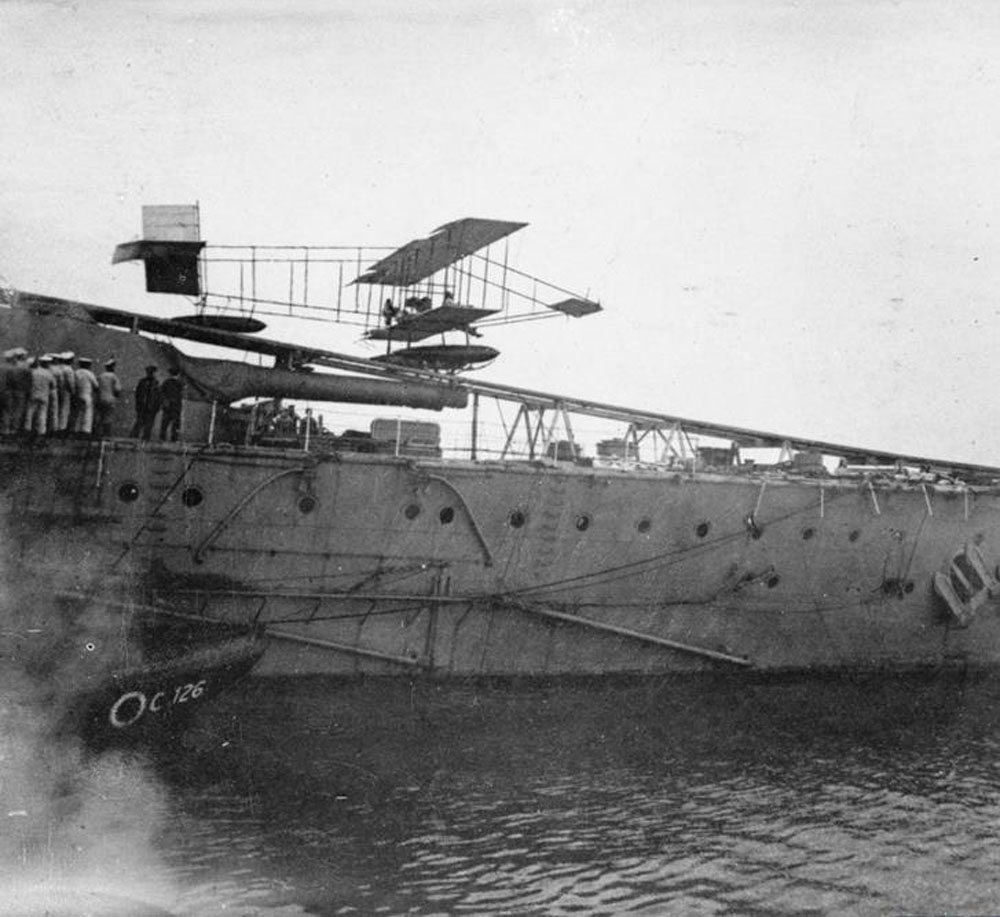

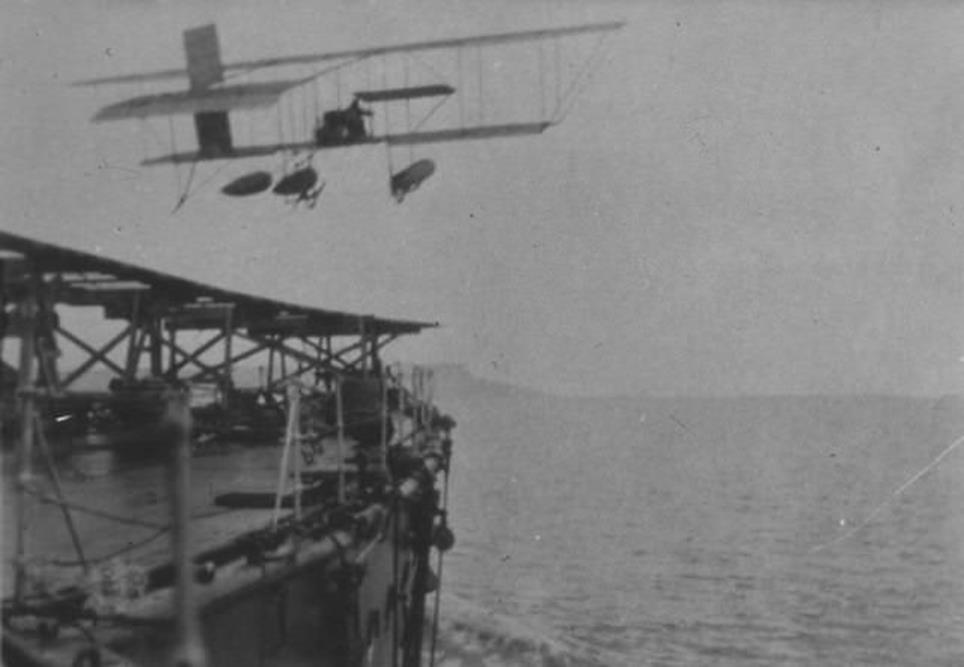

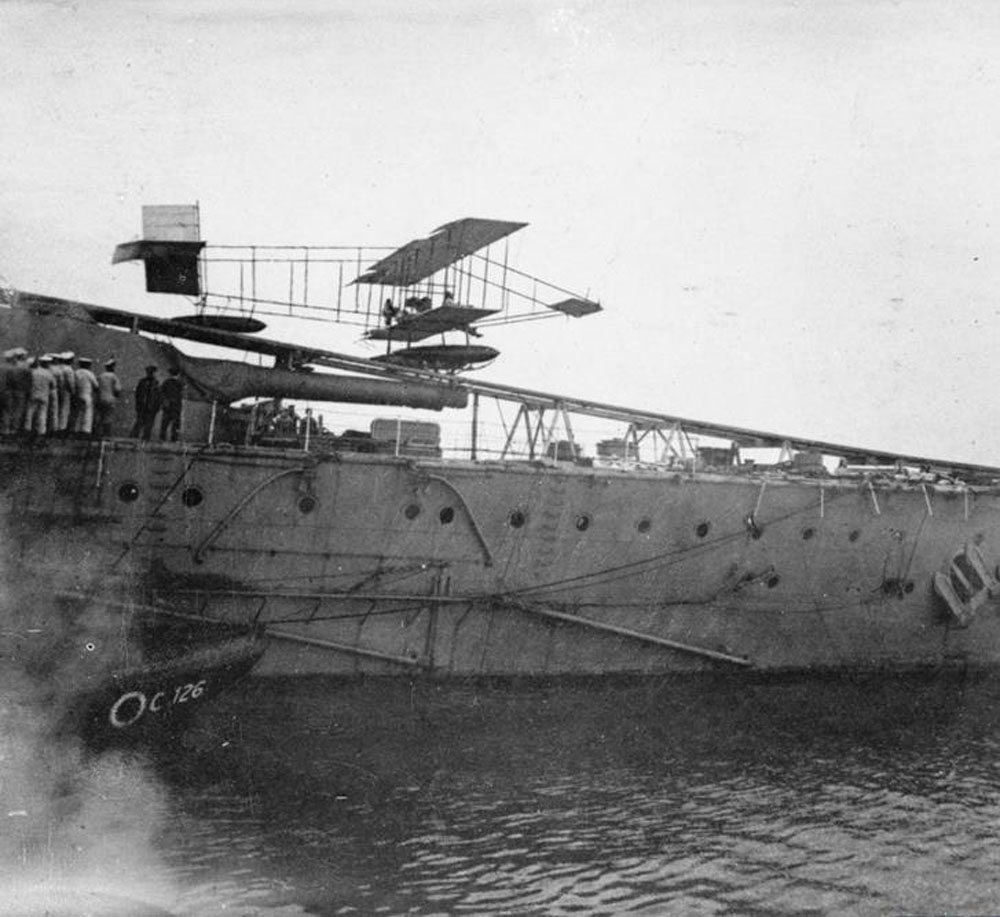

First British take off from a ship

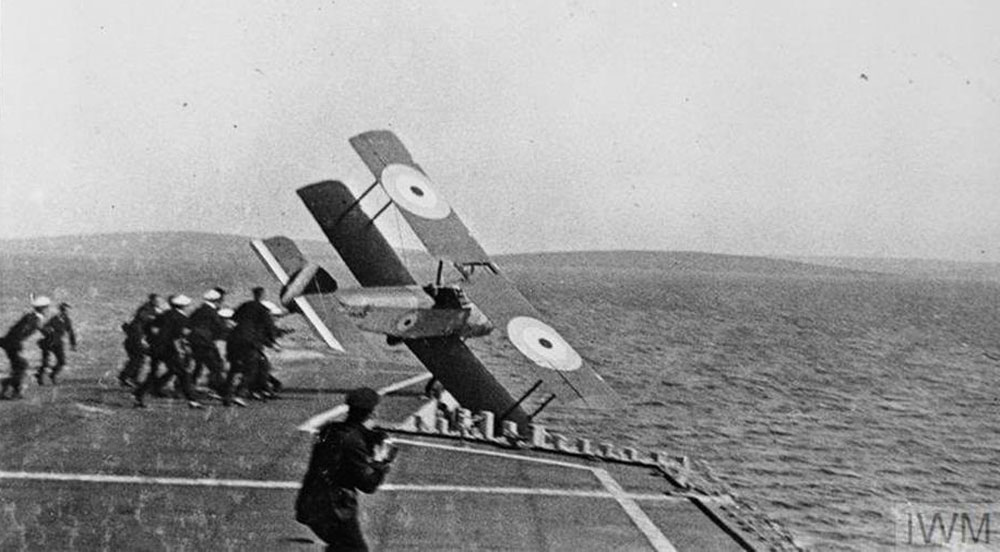

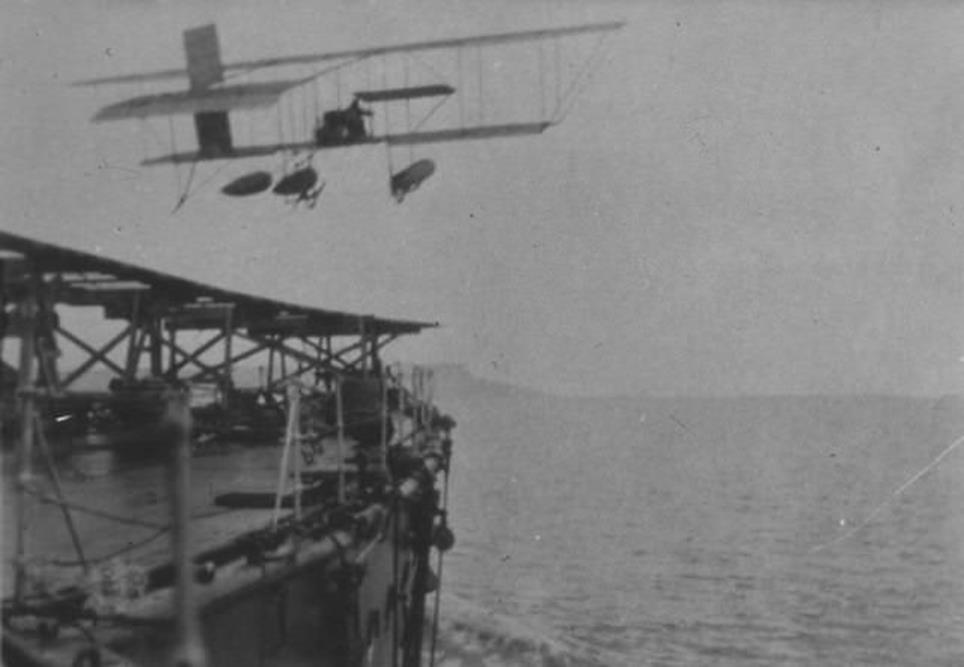

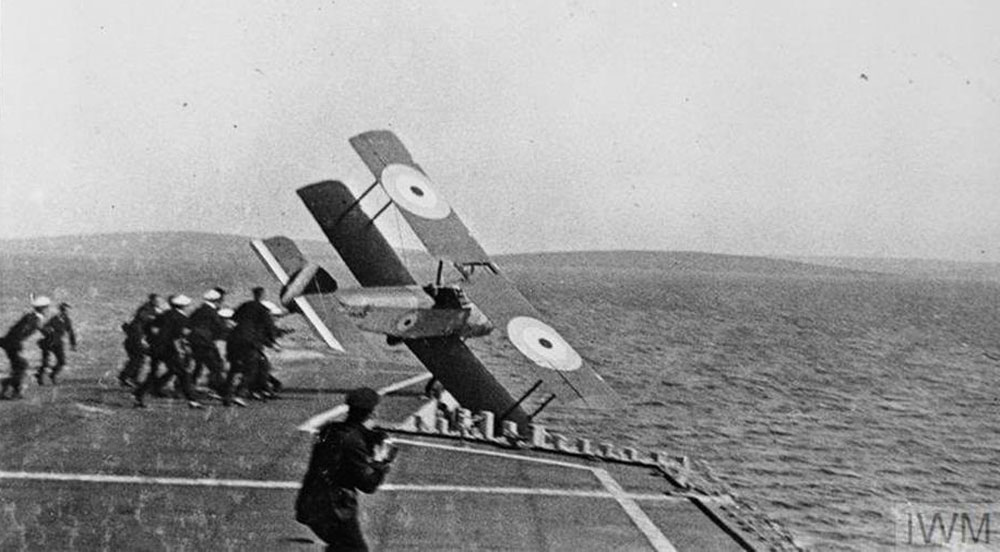

On 10th January 1912, Samson made the first British take-off of a plane from a ship. He flew a Short S.38 from a special ramp erected on the foredeck of HMS Africa, moored off the Isle of Grain in the mouth of the Thames.

Later that year he repeated the feat, this time from a moving ship.

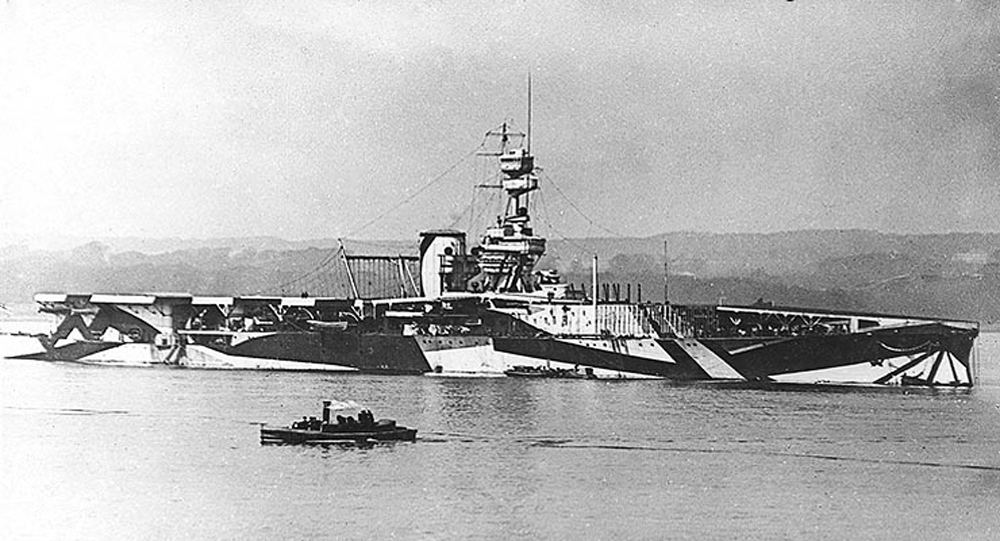

For the 1912 Royal Fleet Review at Weymouth, HMS Hibernia was fitted with a similar flying off platform. On the 2 May 1912 Lieutenant Samson, flying a Short-Sommer pusher biplane S.38, No. T.2, made the first ever take-off from a moving ship, The Hibernia steaming at 10.5 knots. Samson took off when the Hibernia was three miles off Portland Harbour. He rose to 45ft and then landed at the eastern end of Lodmoor.

1912 Government decides to create a chain of Air Stations

The success of these early experiments with what were then known as “hydroplanes”, and the growing threat of war in Europe led to the Government’s decision to deploy a chain of air stations associated with the naval bases along the east coast from Orkney to the Thames.

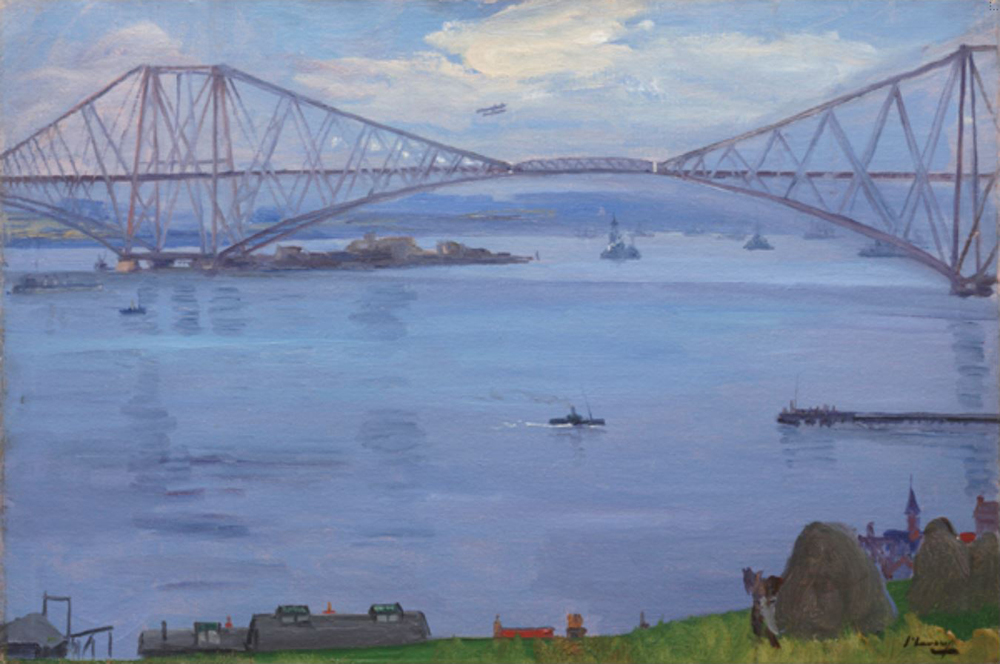

The first naval air station in Scotland was sited at Carlingnose Beach, or Port Laing, in North Queensferry, close to the new naval base at Rosyth.

1912 – Hydroplane station for North Queensferry

The Scotsman – Friday 30th August 1912

HYDROPLANE STATION FOR NORTH QUEENSFERRY

It was ascertained at North Queensferry yesterday that the Government have decided to establish a hydroplane station on high ground above North Queensferry, in the vicinity of the present forts near the War Office ground at Port Laing.

From this point it will be possible to make searches at any time up and down the Forth, and the new department will probably act in cooperation with the Channel or North Sea Fleet so far as scouting operations are concerned. To the east of Carlingnose, the highest point of the promontory, -·there lies at great depth a fine stretch of sand, upon which a former generation of West Fife people were accustomed to disport themselves without let or hindrance, but which is now practically closed against the public. There is an inclination to believe that Carlingnose will ere long supersede Leith Forts as the headquarters for artillery training.

The Scotsman – September 1912

ARRIVAL OF A HYDROPLANE AT PORT LAING

Yesterday afternoon a lighter conveying the first of the Admiralty hydroplanes arrives at Port Laing, near North Queensferry, at a time when the tide was full. On the arrival of the vessel at the pier passers-by along a favourite walk observed lying in the bow a huge rectangular packing case, bearing the lettering, “Aeroplane, Henry Farman.”

For transportation from ship to shore a large squad of men were in readiness to handle the curious cargo, which is destined to form an arm of defence for the Forth Bridge and Rosyth Dockyard. A narrow gauge railway running between the pier and the permanent buildings, at one time used to convey the heavy mines for their shipment to various points in the Forth, will probably be brought into requisition for the conveyance of the air craft.

Preparations for the housing of the hydroplanes are being proceeded with rapidly. Sites for the hangars have been selected near the shore at the base of the Ferryhills, where workmen are levelling the ground. Messrs Cowieson & Company, Glasgow, who have obtained the contract for the construction of the hangars, had a staff of men in the district yesterday with a view to the work being begun, but as the metal sheets had not yet arrived they were unable to start operations. The expectation is, however, that the hydroplane sheds will rapidly take shape, and that sea scouts will soon make themselves manifest in a quiet way.

Gates for Rosyth Dockyard

The arrival of the first hydroplane is not the only indication of the Admiralty’s intentions regarding the protection of the Forth and its great bridge at Queensferry. Messrs Arrol & Company, Glasgow, who were the successful offerers for the construction of the gates for Rosyth Dockyard and the caissons connected therewith, have already formed a huge establishment on the site of the old railway pier at North Queensferry. So far the firm’s workmen have been engaged principally in forming a slip which is to be used for the launching of the caissons, some of which will hold 1200 tons of steel. In order to cope with this undertaking powerful cranes will be erected.

Having been built on the Railway Pier at North Queensferry, the caissons were towed up river to Rosyth.

1912 – NEW SCHEME FOR THE EAST COAST

The Scotsman, Thursday 19th September 1912 – Page 10

AEROPLANES AT ROSYTH

The arrival of a Farman hydroplane at Rosyth marks the first step in the creation of an important naval aviation centre that is to be formed here, and important developments are to follow very shortly. A large tract of land has been secured at Carlingnose, near to the Forth Bridge, for the establishment of yet another of these aviation centres that will in due course extend in a chain from Dover in the south to the Orkney Islands in the north. The stations that have already been established are at Dover, Eastchurch, in the Isle of Sheppey Harwich, and one just in its preliminary stages on the Humber.

The primary object of the Rosyth station is to defend the new naval base, the Forth Bridge, and the estuary of the Forth. In due course, not only will at least four hydroplanes be constantly maintained here, but a fleet of aeroplanes as well. The site secured extends to about twelve acres in all and is said to be admirably adapted to the purpose now in view. It will be under the joint control of the naval and military authorities, and its cost of construction and maintenance will be borne jointly by the two Services in proportions yet to be agrees upon. It is intended that in due course rather a large staff shall be maintained here, and some use will be made of the centre as a training ground for recruits to the Royal Flying Corps and for training those naval officers who decide to take up this wing of the Service in the future.

FLYING OVER THE FORTH

So soon as the Rosyth station is in complete working order the machines stationed there will be constantly employed in testing their paces in the Firth of Forth, with various expeditions seawards. The true value of a hydroplane of the Farman pattern is but very imperfectly realised at the moment, while its potential worth to the fleet can only be guessed at. And there is no real data by which these guesses can be proved or disproved. The destroyers now told off to protect the Firth of Forth will be able to adopt a much wider radius of action, and to remain at sea for longer periods than was previously the case, since the aircraft to be maintained at Rosyth will be available for scouting purposes every day, and will be able to make prolonged expeditions out to sea. A definite range of coast will be assigned to the new centre, and this will probably be from Scapa Flow in the North, to the Tyne in the South.

Close to this new aviation centre will be the wireless telegraphic station that is being built at Rosyth, while experiments with light wireless installations upon aeroplanes are in contemplation at the present time. The principal duty of the aeroplanes and hydroplanes maintained at Rosyth however, will be to patrol the shores of the North Sea and to report any untoward happenings there to the shore authorities and likewise to any warships that might be in the vicinity. It is not yet decided how many machines shall be deployed here, but in due course this number is likely to be considerable.

REST STATIONS.

So soon as it is considered that Rosyth is thoroughly protected by means of hydroplanes and aeroplanes, a commencement with the next northerly station will be commenced. As at present arranged, this will be in the neighbourhood of Scapa Flow, and will not need to be upon such an ambitious scale. Convenient “rest stations” will be set up, both north and south of the Firth of Forth, one being probably situated on the Firth of Tay, within easy reach of Dundee, and the other somewhere in the neighbourhood of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

At each of these an aviator will be able to halt in the event of unfavourable weather or any minor accident or breakdown occurring to his machine. Petrol and other necessities will be stored at each of these “rest stations” which will be under the control of a small staff of experts, qualified to carry out repair work sufficient to enable a “lame duck” to reach its headquarters, where thorough overhauling and refitting will be carried out. The workshops ultimately to be provided at the new centre near Rosyth will be of a very extensive and complete character. While it is not intended at the moment that any construction work shall be undertaken here, the plant available would of course be quite sufficient for this, with the exception of the actual manufacture of the engines should the necessity ever arise. It is quite certain, however, that experimental work of a very important character will be carried out here, and it is probable that important improvements to both aeroplanes and hydroplanes for work in the Firth and the North Sea beyond will be envisaged.

HYDROPLANES AND SUBMARINES

The hydroplanes now to be stationed near Rosyth will in due course be called upon to work in close co-operation with the submarines that will shortly be based permanently in the Firth of Forth. It has been proved conclusively during the past few months that much useful work can be carried out by this joint effort, the hydroplane skirmishing high in the air to ascertain as precisely as may be the movements of a hostile fleet, and then returning to where its assisting submarines are lurking, and conveying this information to them in order that they may strike home. So far no really efficient means of signalling between hydroplanes and submarines has been discovered; but this is probably only a matter of a few years, and some modification of wireless telegraphy will doubtless be devised to meet the situation. It is also suggested that officers serving either in the Flying Corps or the Submarines, should have practical experience of the other arm, so that they may more readily gather what is going forward and be alert for signs that might otherwise pass them by. Therefore, there is a scheme under consideration for the training of naval officers both in submarine and hydroplane work, calling upon them to take turn and turn about in each of these engines of modern warfare.

The ultimate extent of the new aviation centre on Carlingnose cannot be gauged at the moment.

It will thus be seen that a very important era in the aerial defence of the East Coast of Scotland is about to be inaugurated with the arrival of the first Farman hydroplane, and it is quite impossible at the moment to forecast the true significance of this. It is likely that the whole of our present dispositions for the defence of the Scottish coast-line bordering upon the North Sea will undergo very considerable modifications, and these will affect both the Army and Navy alike. In due course the new centre, when it is sufficiently advanced, will be visited be the heads of both services in order that its future possibilities may be carefully studied on the spot and developments suggested.

HYDROPLANES STATION OPENED AT NORTH QUEENSFERRY

Scotsman – Thursday 3rd October 1912 – Page 9

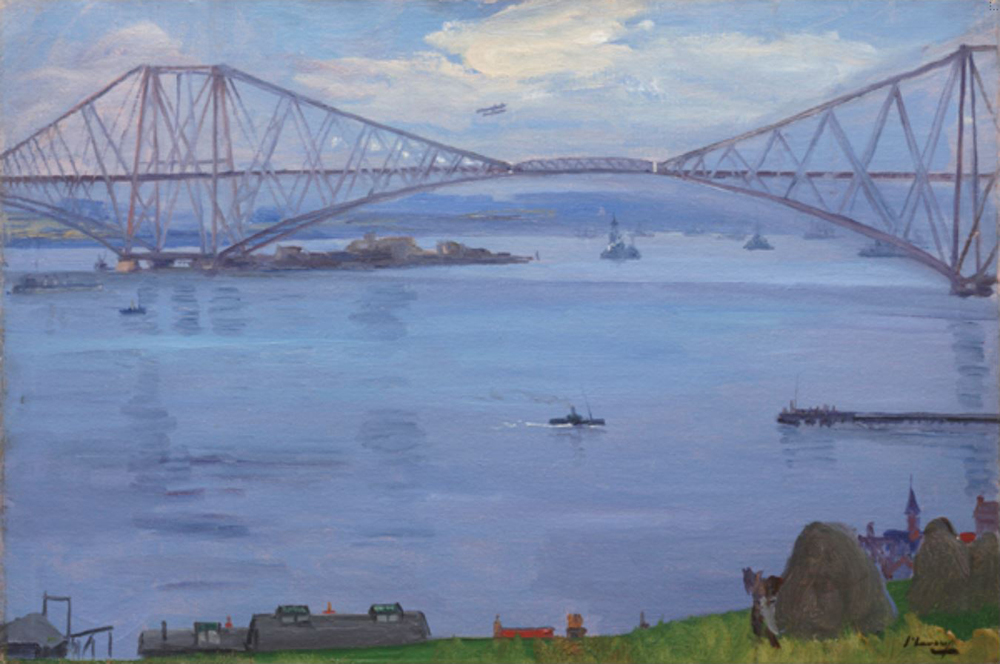

FLIGHT OVER THE FORTH

Yesterday forenoon the new hydroplane station established at Port Laing, near North Queensferry, was opened by two flights being carried out by Commander Samson and Captain Gordon. Three machines have been placed in the hangars, and would have operated previously, but the very stormy weather experienced at the beginning of the week precluded all possibility of any attempt at flying being made, more especially as the wind has been persistently from the east and north-east.

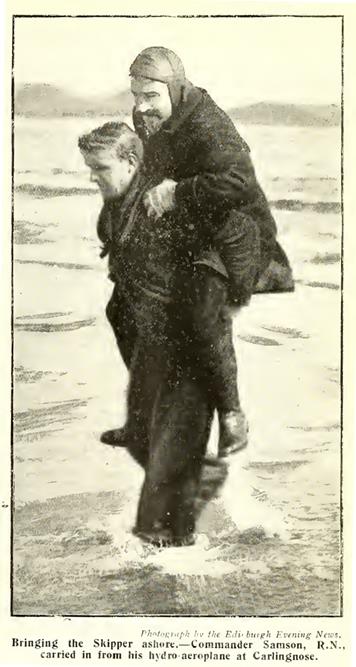

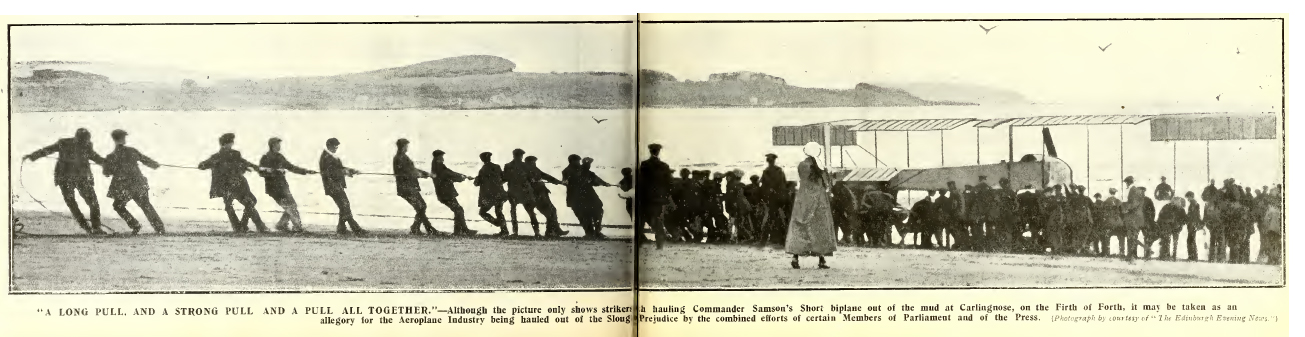

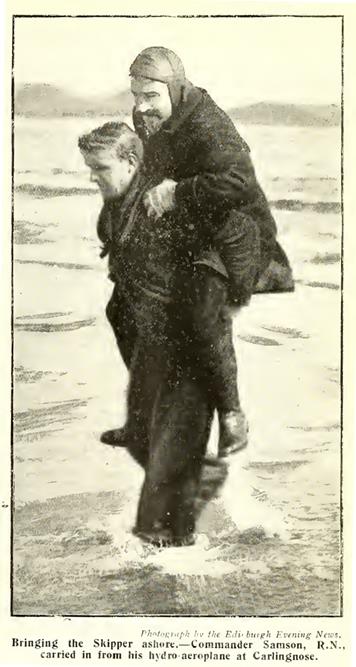

With the improvement which has set in in the weather during the night, it became known that flying would be engaged in yesterday morning and at a comparatively early hour people were seen concentrating on Port Laing form the surrounding district. When the hangar of No. 10 hydroplane was thrown open Commander Samson, having made a preliminary examination directed its removal to the sandy beach whence it was launched by a strong force of bluejackets. The carrying wheels however, lodged in the soft sand at high water mark, and the services of some fifty navvies on strike from Rosyth Naval Base were called to the aid of the launching party, and the machine was soon dragged again to solid ground.

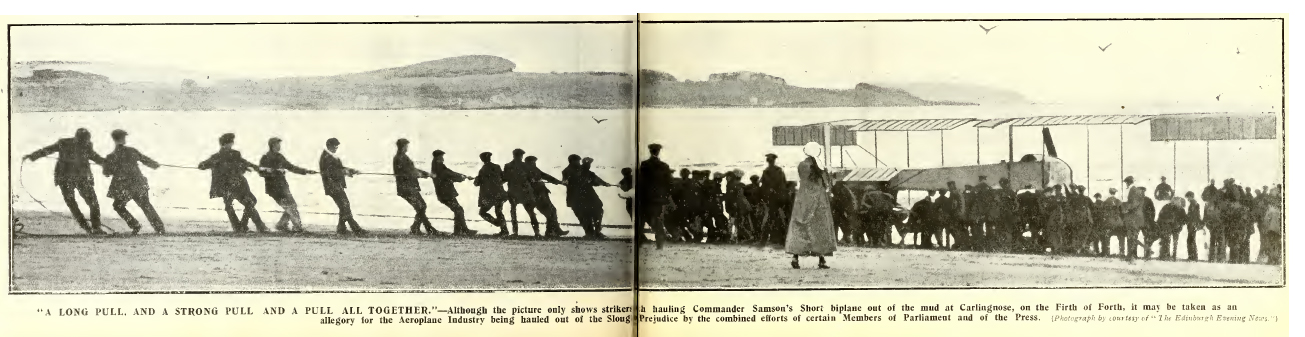

“A long pull and a strong pull all together” – Although the picture only shows strikers from Rosyth hauling Commander Samson’s Short biplane out of the mud at Carlingnose on the Firth of Forth it may be taken as an allegory for the Aeroplane Industry being hauled out of the Slough of Prejudice by the combined efforts of certain Members pf Parliament and the Press.

From a more satisfactory launching ground the biplane was soon riding in the light surf, which was coming in with the rising tide, and at 11.47, with a mechanic on board, Commander Samson set his engine in motion and sped over the surface of the water. In two minutes the aeroplane, steering a course north-east by east, into the teeth of a fresh north-easterly breeze rose from the water into the air, and sailed gracefully and rapidly away in a straight line for Inchcolm Island. Passing the island to the south at a moderate height, the plane again came down to the surface, gracefully swept to the right into a southerly course, and then again round to one for the Forth Bridge. When off Dalmeny Park a deviation towards the north was again made, and rising once more from the sea it swept round and made a line for the landing place, coming one more to the surface before it was safely beached, about fifty yards from the water mark. Commander Samson expressed his satisfaction at the working of his engines. Afterwards Captain Gordon ran out his No. 5 hydroplane, supplied with a seventy horse-power engine and thoroughly tested it on the beach. A circuit similar to that made by No. 10 hydroplane was also most satisfactorily accomplished.

It is learned that operations on a more extensive scale will take place today.

The Aeroplane – OCTOBER 10, 1912 Page 366

Naval and Military Aeronautics. – GREAT BRITAIN.

The new naval aeroplane base at Carlingnose, near Rosyth, on the Firth of Forth, was officially used for the first time on October 2nd, when flights were made by Commander Samson, R.N., on a 100-h.p. Short tractor hydro-biplane, and by Capt. Gordon, R.M.L.I., on a Short 70-h.p. hydro-biplane. The handling of the machines on the muddy beach appeared to be somewhat difficult, and a number of navvies on strike from Rosyth lent a hand in hauling them ashore.

It will be remembered that a considerable time ago it was pointed out in The Aeroplane that, in view of German aeronautical activity at Heligoland and Wilhelmshaven, it would be necessary for us to establish stations for coast defence aeroplanes along the east coast. A certain amount of work has already been done at Harwich, but Carlingnose is the first properly-established station. No doubt, in due course, similar stations will fee made at Tynemouth, Teesmouth, in the Wash, and at other points along the coast. It is already announced that a station is to be established at Cleesthorpe to guard the mouth of the Humber.

Captain Gordon unfortunately turned the 70-h.p. tractor over on Friday. The incident is described by an eye-witness as follows :—” I had a rather good view of the capsizing of Captain Gordon’s Short machine on Friday afternoon, as I was watching him throughout his trip with a telescope. He was travelling on the water, seemingly throttled down, with the wind dead astern, and the machine evinced tendencies to plunge the right wing-tip into the water, and seemed unstable on the float. He then tried turning—not very gradually—to the right to bring himself head to wind for rising. As he turned the wind lifted his right planes, and the passenger (Lieut. Hewlett) climbed out at the starboard side of the fuselage and stretched out to the first inter-plane struts to counteract the side wind. This was not sufficient, and when broadside on to the wind the machine dipped the port lower wing-tip. The pilot immediately switched off, and the propeller entered the water practically at rest. The machine then slowly did a somersault to port, the passenger climbing out on top as it turned. Captain Gordon did not appear till later, but eventually joined his passenger on top. The machine floated towards one side, and of course down by the head. Assisted by fleet boats, the machine was towed back again.”

October 1912 – Flying Over the Forth

Flight Global – October 19th 1912

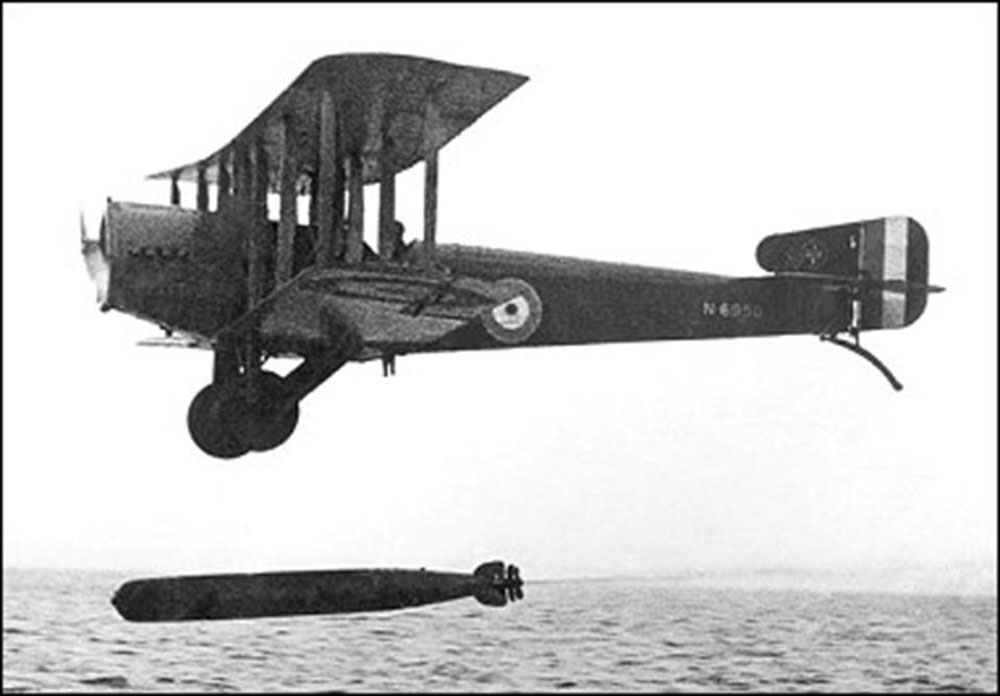

SOME splendid flying was seen from the Carlingnose aviation base on the Firth of Forth at the end of last week, and each day Commander Samson, Capt. Gordon, and Lieut. Hewlett were in the air. A number of experiments in bomb-throwing and in reconnoitring over torpedo boats and submarines have been carried out, while a large number of passengers, mostly naval officers, have been taken for trips. Lieut. Hewlett also carried out some tests in signalling to warships by means of a syren. The flying has attracted large crowds each day, who have witnessed the work from Port Laing, North Queensbury [sic]

The Sphere – April 1913, page 65

Some interesting experiments have been made in the course of the flying week at Rosyth to test the visibility of a submarine when viewed from above. The experiments were of a similar nature to those made by “The Sphere” in the English Channel last year. The recent Forth experiments showed that the water of the Forth is sometimes too muddy to enable the hydroplanes to see the submarine even when viewed directly from above. Yet the hydroplane could always “spot” its submerged enemy: the swirl of bubbles and foam which rode in the wake of the submarine was an infallible index to its position. The experiments confirmed the expected use of the hydroplane in this direction. The machine shown here is the 70 hp Short biplane converted into a hydro aeroplane by the addition of floats.

Short Aircraft used at Carlingnose

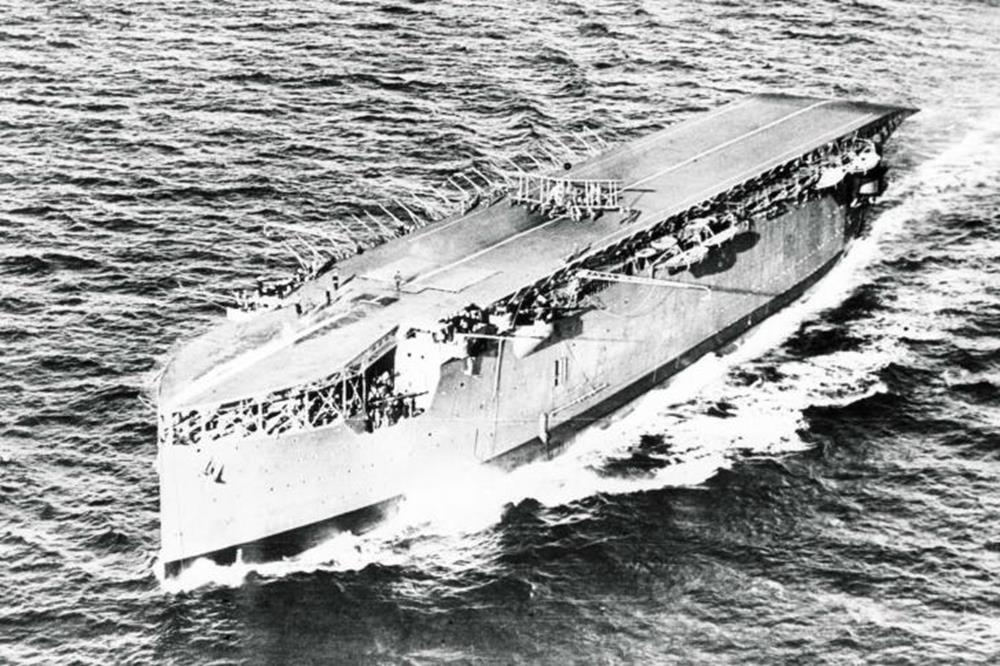

Short Tractor Biplane S.45 Type.

Four aircraft built at Eastchurch. Two-seat trainer that could be fitted with wheels or floats.

Length 35ft 6ins (10.80m). Wingspan 42ft 0ins (12.90m).

Engine (S.45) 1 X 70hp Gnome 7-cylinder rotary. Max speed 60mph.

Serial No.5. Originally numbered T.5. Became No.5 by 2 September 1912. Cost £1184. Shorts construction No. S.45.

Delivered to Eastchurch Flying School 23 May 1912, first flight next day. The aircraft was fitted with floats to take part in the Royal Navy Review at Portsmouth 3 July 1912.

Photo shows No. 5/T.5 at Portsmouth for the Royal Review, July 1912. Aircraft fitted with single central float and airbags under each wing.

The aircraft was damaged 13 July 1912 and returned to Shorts at Eastchurch. Here it was given a new cowling, a coaming around the cockpits, greater span on the upper wings and revised ailerons.

Fitted with wheels it took part in army manoeuvres in September 1912. Refitted with floats it served at Carlingnose Seaplane Station near Rosyth until it capsized 4 October 1913 and was deleted.

No.413 (Shorts c/n S.48) was delivered as a landplane to the Central Flying School at Upavon in October 1912. It was damaged beyond repair in a landing accident 3 December 1912.

Nos 423 and 424 (S.49 and S.50) were delivered to the CFS in February 1913. They were transferred to the Admiralty in August 1914. It is uncertain if they entered service with the Royal Naval Air Service.

Short S.41 “Hydro-Aeroplane”.

The original version of the S.41, it was converted to a landplane and flown by Cdr R. Samson – also the pilot of its maiden flight – during the Army manoeuvres of September 1912.

With its floats restored, it started flying from the temporary seaplane station at Carlingnose on October 2nd 1912.

In January 1913 it underwent an overhaul during which the centre section gap was covered.

In September that year it was overhauled again and the aircraft emerged completely different in shape, fitted with folding wings of greater span and a new rudder.

In 1914 it was refitted with a 140 hp Gnôme and assigned to the Eastchurch flying school.

In 1915 the S.41 was sent to the Aegean theatre and in 1916 was spotted at Inbros.

Not included in the March 1916 list of naval aircraft, it may have been destroyed prior to that month.

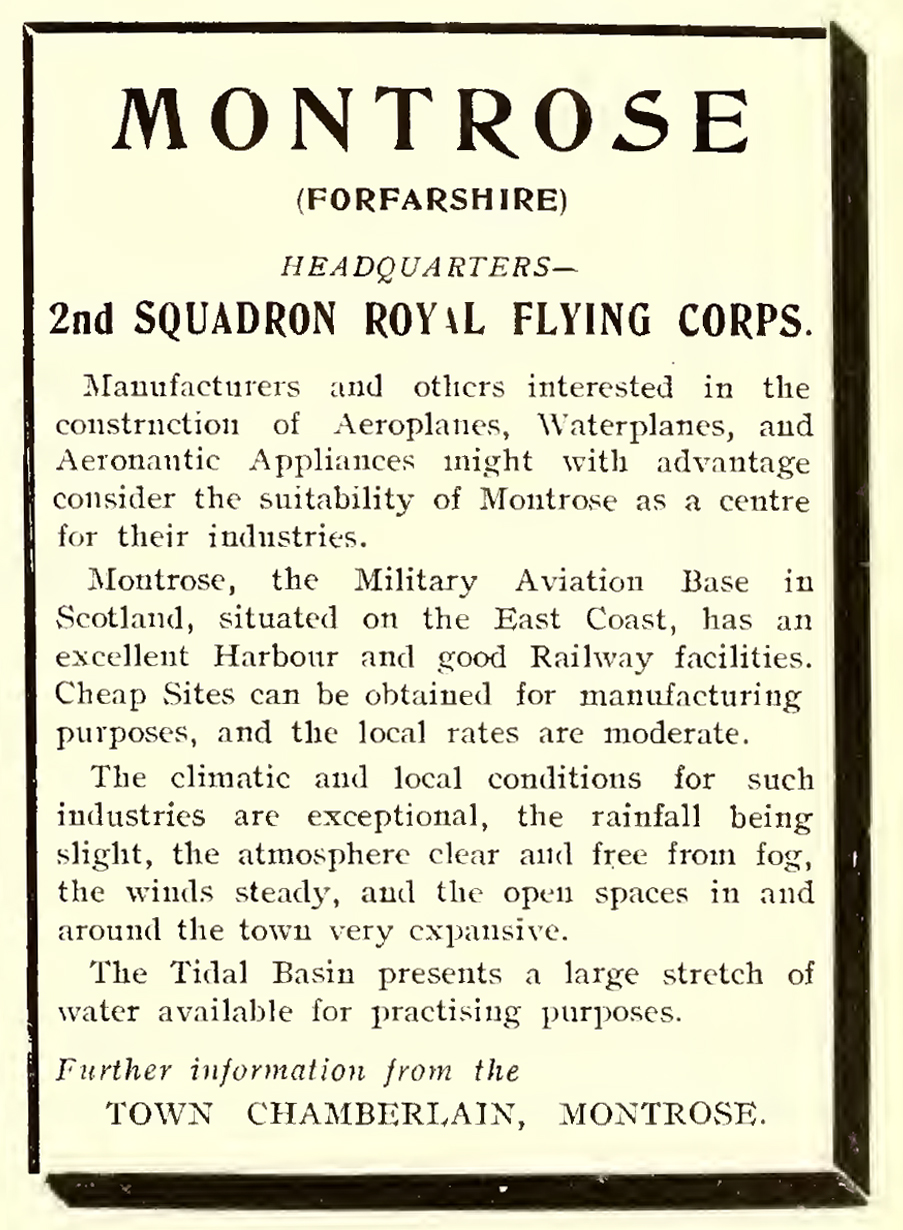

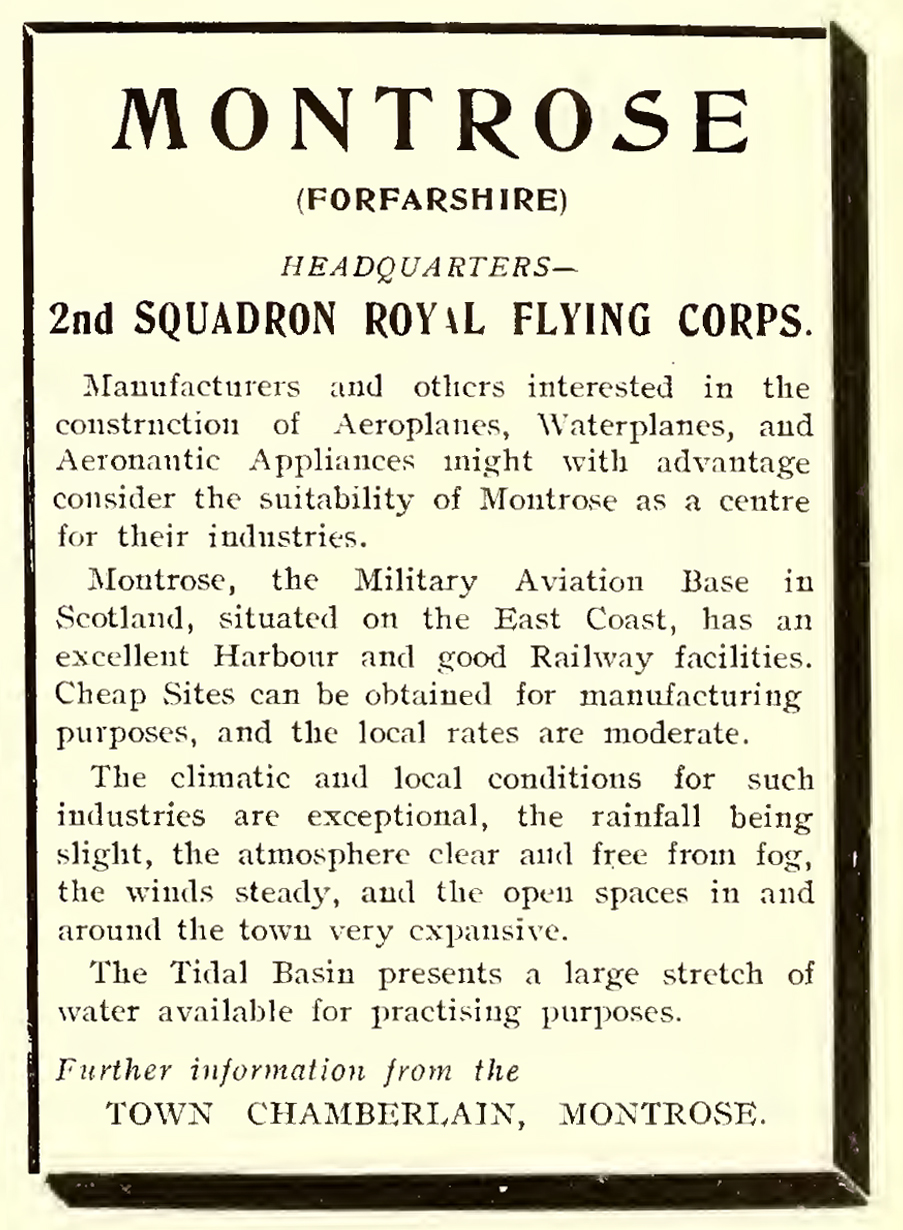

1913 – The Royal Flying Corps Air station at Montrose

While flying continued around the Forth during 1913, the newspapers became interested in activities further north, where the Military Wing of the RFC announced the establishment of their new Air Station in January 1913.

The Aeroplane. January 16, 1913 – The First Scottish Military Station.

One learns that the first of the Military aviation stations to be established at any considerable distance from headquarters is to be opened during the next few days at Montrose in Scotland. This will presumably be the chief military aviation station in Northern Britain, and situated as it is on a comparatively flat coast almost midway between Dundee and Aberdeen, it should be an excellent point for patrolling that portion of the east coast. The second squadron of the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps is to be stationed there, and it is very probable that a Naval station will be formed at the same place

If the two stations are to be combined some interesting problems of Service precedence are likely to arise owing to the temporary rank of Army officers possibly making them academically senior to Naval officers who are not only their senior in rank but are actually their seniors in the Royal Flying Corps. However, it is hoped that no serious friction will arise between the Services.

The Aeroplane. February 13, 1913.

The Montrose station of the Royal Flying Corps has been established on 62 acres of land at Upper Dysart, 3½ miles south of the town and quite a mile from the coast. Its height above sea level is 300 ft. Though probably a permanent station, the land has only been taken on a five years’ lease.

Twelve canvas hangars are erected at present.

The Aeroplane. February 20, 1913.

On Thursday afternoon last [13th February 1913], five biplanes, three Maurice Farmans and two B.E.’s, all Renault-engined, set off from Farnborough on the first stage of the Montrose adventure. Captain Longcroft led the way at 2.30 p.m. on a B.E., after him at short intervals came Lieut. P. W. L. Herbert, Sherwood Foresters ; Capt. G. W. P. Dawes, Royal Berks ; Lieut. F. F. Waldron, 19th Hussars, and Capt. J. H. W. Becke, Sherwood Foresters, who is in charge of the flight. All are first-class pilots. Towcester was the first objective, the original route being altered on account of fog in the Thames valley.

The pilots were unaccompanied by passengers. A fleet of cars and motor lorries followed by road equipped with tools, spares, and stores. This was under the charge of Lieut. H. P. Atkinson, R.A. The landing places proposed are Towcester, Newark, York, Newcastle, and Edinburgh.

Three machines came down at Reading; the others returned to Farnborough, owing to fog.

This migration of a squadron to Scotland is part of the system according to which the R.F.C. is being developed.

From their preliminary training at the Central Flying School, at Upavon, it is intended that the military pilots shall pass to Farnborough, where their training is carried further, and the squadrons formed. As each squadron completes its training, it is to be despatched by air to its permanent post; Montrose being the first of these stations to be formed away from headquarters.

The flight of No. 2 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, was continued on February 17th, despite a very high wind. Captains Becke and Dawes and Lieutenant Herbert left Reading about 9 a.m., and Captain Longcroft and Lieutenant Waldron left Farnborough some two hours later. Captain Becke arrived at Towcester at 2 p.m., after one stop for petrol at Blakesley. One other pilot landed at Moreton-in-the-Marsh, one at Aylesbury, and Captain Longcroft and Lieutenant Waldron at Oxford.

The Aeroplane. March 6, 1912 – The Montrose Flight.

The five Army aviators who have been repairing from Farnborough to Montrose happily reached their journey’s end on Wednesday, February 26th, having been thirteen days on the “road,” the speed average thus approximating to 1.24 m.p.h.

On Tuesday (February 25th) all five left Newcastle, and four of them—namely, Capt. Becke (“B.E.”). Capt. Longcroft (“B.E.”), Capt. Dawes (Maurice Farman), and Lieut. Herbert [Maurice Farman)—arrived at their destination, Edinburgh. The fifth—Lieut. Waldron (Maurice Farman)—descended near Little Mill, Northumberland, and then flew on to Berwick, whence he proceeded on the following day to Montrose, as did the others from Edinburgh.

The main point which stands out in connection with this flight is the pluck and determination of the five pilots. It is difficult to conceive why the worst possible season of the year should have been chosen for this demonstration, which, so far from constituting a much-needed advertisement for aviation, has had, rather, the effect of confirming public disbelief.

“For,” says the Man-in-the-street upon perusing this record of short daily mileages, of long halts and occasional mishaps, “if this is all that aeroplanes can do, let us await further development before we begin spending money on them. ”

That may or may not be sound commercial philosophy; politically, it is mischievous to the point of suicide; moreover, the Montrose flight is not a fair measure of the modern aeroplane’s capabilities.

As regards Capt. Becke’s unpremeditated decent at Doncaster, Mr. D. W. Cook writes that Mr. Egglestone, of the firm of Wyatt and Egglestone, motor engineers of Doncaster, who had the repairs in hand, reports that one of the cylinders of the Renault engine blew off and the connecting rod swung round loose as the crankshaft continued to revolve, until the end of the rod came out through the crank-case and locked the engine. The tractor screw did not break, but the propeller shaft was twisted round nearly three-quarters of a turn. No other damage was done to the machine, except that a small hole was knocked in one of the planes.

Mr. Egglestone was of the opinion that the direct cause of failure was not due to a piston jamming through faulty lubrication, but that the gudgeon pin breaking with an oblique fracture had probably twisted and caused the two parts to force nut into the cylinder walls, the pin being broken in such a wav as to suggest this.

Mr. G. T. Cooper, of Edinburgh, writes :—

“On Wednesday, February 26th, Edinburgh saw the Armv aviators flying over the centre of the city in order to reach their landing ground at Colinton, which they had the greatest difficulty in finding owing to the fog. Capt. Dawes, in fact, landed a mile away, flying over later in the afternoon. The aviators were for starting off a; once for Montrose, but as the fog began to get thicker and difficulty was experienced in getting petrol, they decided to spend the night in Edinburgh.

“In the evening all of them, except Lieut. Waldron, who had not reached Edinburgh, having descended at Berwick, were ‘entertained to a dinner given in their honour by the Edinburgh Aeronautical Society.

“The next morning, owing to a thick Scotch mist, it looked as if the aviators would be unable to go, but shortly before ten the mist rose and the weather conditions become perfect. After a trial flight by Capt. Longcroft, they all set off and, except Lieut. Herbert, who had to descend on account of fog, they all did the trip in very fast time, at about seventy miles an “hour.”

1913 – New Borel Monoplane at Port Laing

The Aeroplane – Thursday March 20 1913

Borel monoplane

In March 1913, the navy purchased the French Borel monoplane.

It appeared at Port Laing in January 1914.

1913 Progress at Montrose

The Aeroplane – April 24, 1913.

The first Military Aerodrome to be established in Scotland is now in working order. The aerodrome consists of a long, narrow stubble field of about 62 acres, tented from the farms of Upper Dysart, at five years’ tenancy. It is situated about 3½ miles south of Montrose, and one mile from the sea coast, the main road between Dundee and Aberdeen running past the end of it. It stands clear of the surrounding country at the height of 300 feet above sea level, and is exposed to winds from all points. The soil is of a soft clay nature covered with short hard stubble. There is one bad hole in the middle front of the sheds, but this is being gradually filled up with refuse and earth.

The sheds, 10 in number, are erected at the east bottom corner, near the road, and are made of canvas stretched on steel tubular framework. The front poles are taken out and the front curtain pulled up for the machine going out and in.

The machines in use at present are two B.E.-2 type, Nos. 216 and 217, and three Maurice Farmans, Nos. 207, 215, and 266, and two new B.E. are expected daily. There is also word of some four or six monoplanes being drafted to this base, but at present the squadron is very much under establishment.

This squadron is composed of about 130 officers and men, under the command of Major Burke. The flight commanders and flying officers being Captains Becke, Longcroft, and Herbert; and Lieutenants Martyn, Lawrence, Pepper, McLean, and P. B. Joubert de la Ferte.

Major Burke, Captains Becke, Longcroft, and Lieutenant Lawrence fly B.E. machines, while the others are Farman fliers. The work done is as yet only reconnaissance flying and taking part in local Territorial manoeuvres. Most of the flying is done between 6.30 and 7.30 in the morning, and from 9 to 11 in the forenoon; and practically no flying is to be done on Saturdays or Sundays. The sheds are open for inspection by the public on Saturday afternoons from 2 till 4 o’clock.

The squadron is quartered in the Panmure Barracks, Montrose, and is conveyed to and from the aerodrome in two Leyland motor waggons, the officers in two Daimler cars. There are also two Phelon and Moore motor-cycles for dispatch work.

Arrangements for regular work are in a crude condition as mechanics are to be seen any day peeling potatoes or doing some such work in the barracks, this is no doubt owing to the lack of machines at the aerodrome. The guard consists of two sets of two men taking turn about for 24 hours of two hours guard and four hours sleep; and are only armed with revolvers, only three machines are in working order at present. Two Maurice Farmans are being overhauled and the planes recovered, leaving only three planes between nine pilots. Last week for three days there were only two machines in flying condition, and, suppose either of them was smashed, the squadron would have been further handicapped. This is an awkward state of affairs, and if the policy of one pilot, one machine (not to mention a spare one) is to be carried out, it is time Squadron No. 2 had a dozen more efficient aeroplanes.

1914 – All Change!

Activities continued at Port Laing and Montrose through 1913, but the growing threat of war from Europe and some local difficulties meant that major changes were just around the corner.

A new Naval Airstation was under development at Carolina Port in Dundee, and orders were received to move from Port Laing to Dundee.

While Port Laing was very close to the Grand Fleet at Rosyth, the conditions at Port Laing were not ideal. The foreshore proved to be sticky, making it difficult to recover planes after they had landed on the water, and the steep cliffs behind the beach would have cause lots of wind-shear, violent up-draughts and down-draughts, that would have affected the handling of the primitive aircraft.

Another factor was the affection for flying displayed by Winston Churchill. He had flown in all types of military aircraft, taking control on several occasions. As he was the M.P. for Dundee, there is little doubt that he was influential in attracting the naval airstation from the Forth to the Tay.

The final factor was the artist Charles Martin Hardie, the owner of Garth Hill in North Queensferry, who had leased the land at Port Laing to the Admiralty. He tried to negotiate an increase in the rent.

The Aeroplane – January 22nd 1914

There has been a considerable amount of flying during the past week by the officers at the Naval Aerodrome at Port Laing. Major Gordon, R.M.L.I. who has been on a tour of inspection in the north for some time, has now returned to the station and made extended flights on a Short seaplane up and down the Forth. He was joined by Capt. Barnby, who has also done some extended flights on the Borel monoplane. Capt. Barnby has done some remarkably high flights over the district. It is expected that operations will continue until the end of March at this station.

Meantime, the good citizens of Montrose were advertising the merits of their location to the growing aviation industry.

1914 the move from Port Laing to Dundee

The Aeroplane – January 23rd 1914

Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., and Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I., started out from Port Laing on Tuesday on Short seaplane No. 42, and alighted off St. Andrews. In attempting to start again the floats were so damaged that the machine was taken ashore.

It was there converted into a land machine by fitting it with wheels. Major Gordon had some trouble with the controls while putting the machine through its tests over the sands, but it got away safely. They arrived at the Dysart Aerodrome on Wednesday, and, on the following day they flew it down to the new aerodrome at Broomfield, where it is now housed.

The Aeroplane – February 5th 1914

The developments of the Dundee base, which have been dormant for some time, now promise to take definite shape. Orders have been received at Port Laing to make ready to move to Dundee. These operations are to be commenced on February 18th. The officers in charge of the station are Major Gordon and Capt. Barnby R.M.L.I. Much reconnaissance work has been done over the Forth, but owing to the “lie of the land,” the locality has proved bad owing to wind-gusts, and the unsuitability of the location has made it necessary to move. This is the third shift to be made by the naval aeroplanes in the district, as they have been at Leven and Port Laing, and now go to Dundee. One imagines, however, that much work will still be done at the mouth of the Forth.

The Aeroplane – February 12th 1914

The work of transferring the aviation base from Port Laing to Dundee is now rapidly going on, the three sheds being dismantled and sent by rail to their destinations. One tent is already on the way, and the skeleton of another was being rapidly demolished when the site was visited. The principal reason for the shift is now understood to be the failure of the owner of the ground and the Admiralty to come to terms. The proprietor, an artist, is apparently holding out for an extraordinary figure. Major Gordon and Capt. Barnaby, R.M.L.I., will fly over Fifeshire to the new station during this week, and it is expected to be in working order by the 18th. The departure of the base from North Queensferry is a keen disappointment to the local inhabitants, whose trade has increased since the aviators came there.

[The artist in this article was Charles Martin Hardie, of Garth Hill, North Queensferry.]

The Aeroplane – February 19th 2014

On Monday, Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., flew from North Queensferry to Dundee on the Borel seaplane carrying Leading Seaman Shaw as passenger. The flight occupied 58 mins, the coast-line being followed all the way, and ended up in a flight over the Tay. The machine was hauled up on the slip and covered up for the day, huge crowds waiting in the cold on the chance of seeing more flying. Next day, much to their disappointment, the wings were taken off and the Borel was taxied up to the dock, where she lies at anchor.

The work of transferring the hangars still goes on, and it is understood that Messrs. Cowieson, of Glasgow, have secured the contract for the erection of permanent sheds at the base – Carolina Port – indication that an extensive scheme is meditated.

The Aeroplane – February 26th 2014.

The work of erecting the sheds at Carolina Port, Dundee, is still being rushed on, and one of them was so far advanced that on Wednesday the Borel, minus its wings, which had been at anchor, was landed on bogies and taken to the shed. The strange sight of the seaplane caused quite a stir. The Maurice Farman has arrived at the base in pieces and will be assembled as soon as the second shed is ready for it. The other machine (Short No. 42) still sits in a hangar at Broomhouse Aerodrome, Montrose. Commander Scarlett was to have inspected the work last week, but has not yet done so.

The Aeroplane – March 5th 2014.

The naval base at Carolina Port, Dundee, is temporarily a land base, as all the flying has been done on Short No. 42 with a land carriage. The sheds are still being put up, but it will be some time before they are ready. They are placed about 100? yards from the banks of the Tay, so that a long slipway will have to be constructed.

On Tuesday of last week Capt. Barnby made a fine flight from Montrose and landed at the port. Flying was done by Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., on the succeeding days, each for about 15 mins. The landing-place is a long stretch of rough ground which is not in the best trim for flying, on one side being the Tay, while the other is lined by telegraph poles. It takes considerable skill to rise and land here, and the officers show much ability in handling their machines.

March 1914 – military manoeuvres at Leven

While work continued at Dundee, the naval aviators took their planes to Leven, on the Forth to take part in some military manoeuvres in March and April 2014.

The Aeroplane – March 12th 2014

The storms of last week made flying impossible at Dundee, but Capt. Barnby took advantage of a lull on Thursday and made two flights on the Short of about 15 mins each. Part of this squadron went to Leven at the end of the week to make preparations for the machines working from there in conjunction with some naval manoeuvres.

The Aeroplane – March 19th 1914

Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I., accompanied by A. M. Rogers, left Dundee on the Short for St. Andrews on Monday, alighting on the sands there, and returned at 2,300 ft., having a rough passage. On Tuesday Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., took the machine to Leven and had to stay overnight there owing to a pipe bursting as he attempted to leave. The Borel, which has been overhauled and altered, was taken out on Wednesday afternoon by Major Gordon. The machine was conveyed about 100 yards, cast off the base on trolleys, and there launched. The first flight of about 20 mins was over the Tay, while in the second A.M. Coleman was taken as passenger, but the engine did not behave well. A third flight was made west of the Tay Bridge at 900 ft. The entire detachment left next day for Leven to carry out manoeuvres there, and the Borel will be flown there when the place is ready for it.

Two Short seaplanes arrived in boxes at Leven last week, and the Borel seaplane No. 86 is expected, and Short No.42 arrived on Tuesday by air from Dundee. About twenty-five men were stationed there at the time, and more are expected daily, with Major Gordon R.M.L.I., in command. Four sheds are in course of erection and all hands are busy at unpacking and erecting machines. It is rumoured that this detachment of the Naval Air Service will remain at Leven for some six weeks.

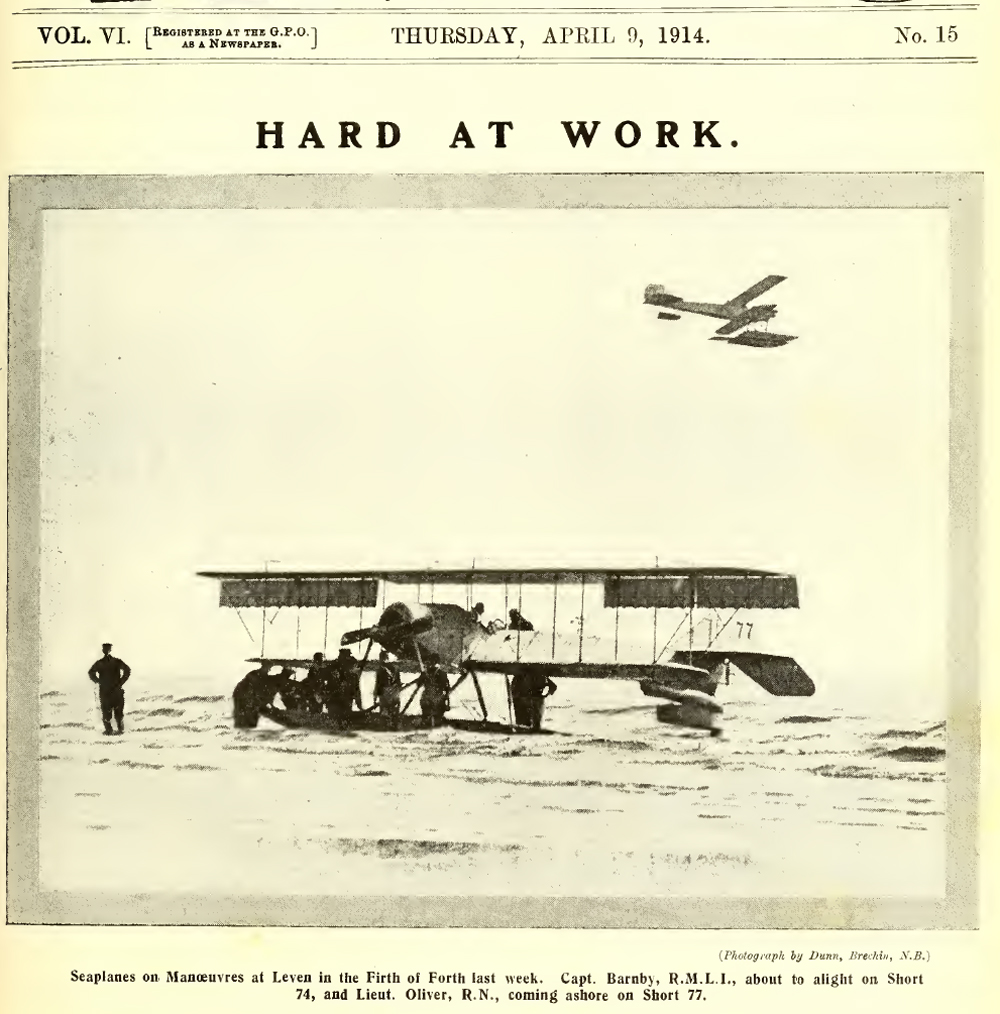

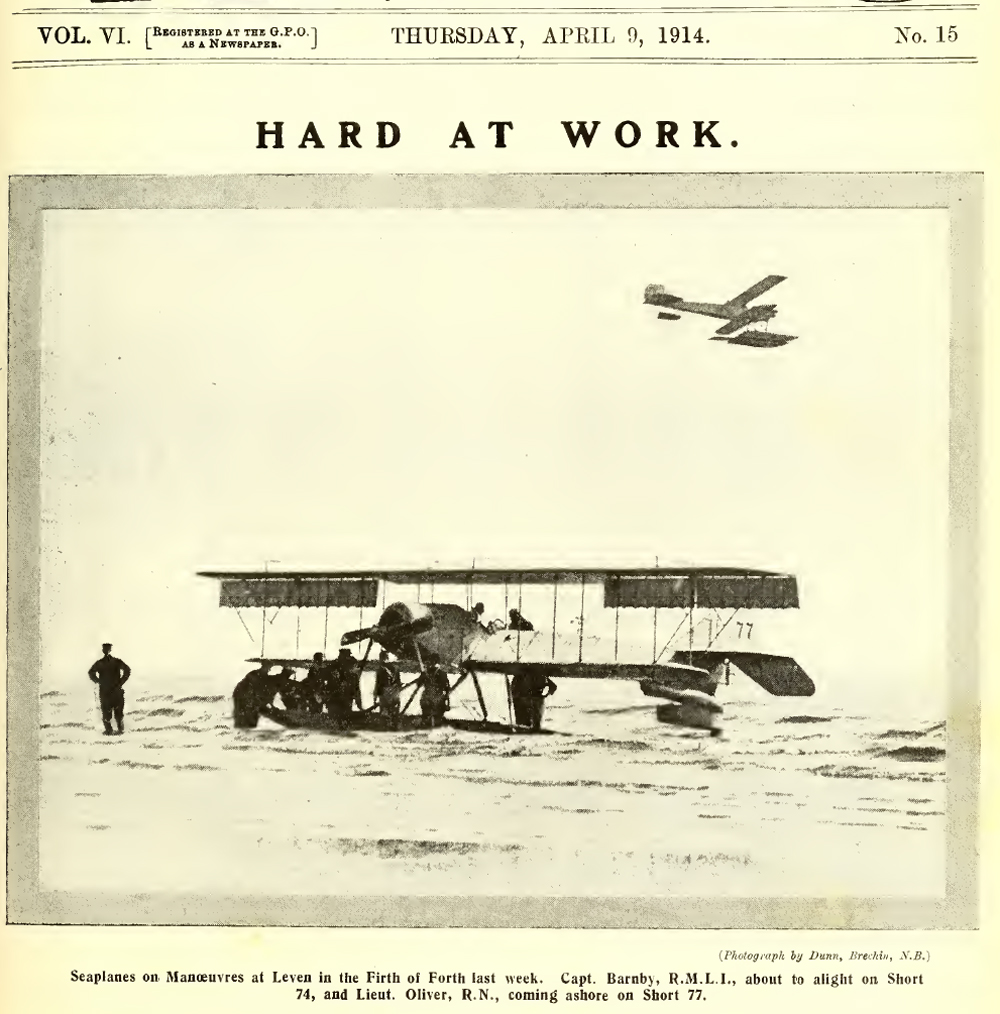

The Aeroplane – April 2, 1914.

Leven was favoured with excellent flying weather during last week, and full advantage was taken of it by the pilots of the Naval Air Service. The unanimous opinion among the corps regarding Leven beach as a flying base is that no better could be got anywhere round the coast. The staff at Leven now includes Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I., Lieuts. Oliver and Chambers, R.N., Fowler, R.N.R., and Ireland, R.N., the first-named being in command, and the last in charge of the wireless installation. There are also about twenty men. On Monday, Lieut. Fowler and P.O. Hendry were testing wireless on Shorts Nos. 74 and 75, and all the officers at the base made short flights during the day. Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., Capt. Barnby, and Lieut. Oliver were out on Tuesday on Shorts 42 and 75. On Wednesday, Lieut. Oliver arrived on the Borel from Dundee, and on Thursday, Lieuts. Fowler and Oliver made several flights on Shorts 74, 75, and 77, and on Borel 86. On Saturday, Capt. Barnby, with Lieut. Chambers as passenger, flew Short No. 42, and Lieut. Oliver made a flight on the Borel.

The slipway between the hangars and the Tay has now been commenced at Dundee base. The only remaining machine here, the Borel, was flown to Leven on Wednesday by Lieut. Oliver, R.N. Shortly after 2 p.m. the machine was trolleyed to about 100 yards east of the sheds and launched. Lieut. Oliver, accompanied by A.M. Vitty, taxied up and down the Tay, but the Borel would not rise. He came back to the port and disembarked a quantity of petrol and made a second attempt to rise, which was unsuccessful. He then shed his passenger and the machine rose and flew to Leven. The base at Carolina Port is now deserted save for the workmen at the slipway, and will be for six weeks while the manoeuvres last.

The Aeroplane – Thursday, April 9, 1914.

During the first three days of last week no flying was done at Leven. All hands were engaged in overhauling and setting in order for the manoeuvres, which lasted till April 3rd. Despite weather conditions being unfavourable for good flying, practically all machines were on active service. The regular staff was augmented by six naval pilots. The men of the wireless department had a busy time of it, and were no doubt, glad when the manoeuvres were ended. All the Shorts have been fitted with wireless. Short seaplanes Nos. 42, 74, 75, 77′ were all engaged, and Borel No. 86. Their work was chiefly reconnaissance; and flying from the mouth of the Firth to Rosyth. All officers had spells of flying.

The machines, and one of the hangars, are, one gathers, going on to Dundee, and the other hangar is to be sent on to St. Andrews.

The Leven correspondent of The Aeroplane writes : — “Yearly a howl arises from a section of the Liberal Party over the increasing Naval Estimates. If those estimable gentlemen whose slumbers are made horrible by a ghostly procession of Dreadnoughts would only go into smaller details of administration, they might achieve some good. Take, for instance, the presence of the Flying Corps at Leven. The men arrived during the first week of March with material sufficient to build four hangars. The best part of a fortnight was spent in putting up two, end the others will not be erected at all. Flying only started towards the end of the week which terminated on March 21st. Five machines were brought. All these expensive preparations were carried out—for what? Not for training the men, but for three days’ manoeuvres. Apparently Leven is the best place for manoeuvres, but no good as a base.”

Several of those connected with the flying say that Dundee is totally unsuitable, because it is out of the track of ships making for Rosyth, whereas Leven is directly in this track. The explanation is simple. The choice of the base lay with Mr. Churchill, and he picked out Dundee, not because Dundee was the best place, but for the reason that his constituents would he gratified by his decision. They may be, but the public generally are well entitled to grumble at money being wasted like water, for no good purpose whatever.” The foregoing is published without expression of opinion, but merely as showing how official actions may be, rightly or wrongly, explained.

The Aeroplane – April 16, 1914.

Practically nothing has been done during the past week at Leven. The staff has been reduced to six, and seaplanes have had a rest. The remainder of the staff, however, are only gone to Dundee for a short spell, and are expected back shortly. The reason why is as yet unknown, to our correspondent, at any rate, Short No. 42 was out on Thursday night, and was piloted by Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., with a Marine as passenger. He circled Largo Bay, and went inland for a bit.

April 2014 – back to bonnie Dundee

The Aeroplane – April 23, 1914.

Dundee naval air base is regaining something of its old activity. The manoeuvres at Leven have now finished and preparations are being made for the return of the machines to Carolina Port.

On Thursday, Major Gordon flew the Borel, No. 86, from Leven to the Tay. Leaving the Forth about a quarter to seven, he made a good flight round the coastline, arriving above Dundee half an hour later. Owing to fog, he was compelled to fly at a low altitude, and before landing he flew up to the Tay Bridge, above which he turned. About 9 o’clock the machine was brought ashore and housed in a Bessonneau canvas hangar. Major Gordon also inspected the slipway which is under construction, but which was badly damaged by the waves during the gales of last week. Stronger and larger piles are now being put in to replace the ones which were washed away, and a much stronger slipway is now to be built than was originally intended.

Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., and six men still remain at Leven, and some little flying continues there. On Wednesday morning (April 15th), Major Gordon flew Borel 86 back to Dundee. On Thursday, with one of his men as passenger. Major Gordon made a half-hour flight on Short 42, and on Saturday morning four flights, apparently on the same machine.

One gathers that the temporary sheds are to be removed, and the station vacated within the next fortnight.

The Aeroplane – April 30, 1914

The transferring of the seaplanes from Leven to Dundee was continued on Monday afternoon, when Major Gordon, with A.M. Usher, flew the Short tractor (100-h.p. Gnome) No. 77 round the coast to Carolina Port. There was a thick haze and the pilot flew at about 500 ft., following the coastline. After entering the Tay he twice circled H.M.S. Vulcan and then glided down to the slipway.

Next morning Capt. Barnby created a new record between Leven and Dundee. At 5.50 a.m. he got into the Short biplane No. 42 and was in Dundee at 6.10 a.m. He then motored back to Leven and flew Short tractor (100-h.p. Gnome) No. 74, with A.M. Croucott as passenger, round the coast to the base. He was followed a little later by Major Gordon on the sister machine, No. 75, carrying A.M. Noonan as passenger. They followed the same route as Capt Barnby and landed shortly after him. Capt. Barnby then took No. 75 and, with Leading Seaman Shaw as passenger, gave a fine exhibition flight over the Tay. Short No. 42 was brought out to the cinder-track and Capt. Barnby flew over Broughty Castle.

On Wednesday, shortly after eleven, Capt. Barnby, on Short No. 77, with Lieut. Curtiss, R.N., as passenger, flew west up the Tay, and after 40 mins came back to the base. He repeated this flight accompanied by Cadet Curtiss, R.N., as passenger. No more flying was done during the week, and the men who were busy dismantling the hangars at Leven have gone on six days’ leave.

By Tuesday of last week all the machines had been flown from Leven to Dundee, and the Bessonneau hangars are now dismantled, nothing but the barbed wire fence remaining.

Prior to the departure of the Short on Monday several exhibition flights were made, and the numerous visitors from Edinburgh and other places had the chance of witnessing the flying. General regret is expressed locally that the Corps are not to be stationed here all the summer. The Town Council of Leven are to make an effort to get a seaplane base permanently established here. Mr. Asquith is to be approached, one learns, but whether the “oracle will work” or not is a matter of speculation.

Permission has been granted by the Town Council of St. Andrews for the erection of two aeroplane sheds on the West Sands, to accommodate aeroplanes which land there occasionally.

The Aeroplane – May 7, 1914.

Flying was resumed at Dundee on Saturday, May 2nd, and the Short tractor 100-h p. Gnome No. 74 was out from eleven to four. Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., made the first flight with .A.M. Johnstone as passenger. He flew up and down the river for 24 mins. Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I.. then boarded the seaplane with .A.M. Wellburn, and flew the same course as the previous flight for 40 mins. Major Gordon again took the Short, and, after flying down the river for some time, turned the machine south and flew to St. Andrews. An hour later he returned, and landed before the slipway. Capt. Barnby then made his second flight, accompanied by A.M. Noonan, and flew from between the Tav Bridge and Broughty Ferry.

After keeping up this circuit for an hour he descended and handed the machine over to Major Gordon, who made the last flight of the day, being in the air about 20 mins.

The Aeroplane – May 14, 1914.

On Wednesday, Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., made a trip from Dundee to St. Andrews on .Short tractor (100-h.p. Gnome) No. 74, accompanied by A.M. Crancott. He circled the “Mars” training-ship and then flew down the Tay and round the coast to St. Andrews, where he landed safely. He then went aboard H.M.S. “Dreadnought” for lunch, after which he made several flights over the bay with some of the officers as passengers. He started back for Dundee at 3.30 and flew at a height of from 500 to 1,000 ft. On Friday afternoon Major Gordon was out again in the same machine, and after a few minutes’ flight was forced to descend with an engine stoppage. He made a second start, but had not gone far when a rainstorm made flying disagreeable, and he landed. He was accompanied by Capt. Fane, of H.M.S. “Vulcan,” and at their third attempt made off in the direction of Montrose. When still five miles from that place they encountered so heavy rain that they turned and came back to Dundee, when the machine was put back in the hangar.

Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.L, and half the men at Dundee went on leave about the middle of the week as the first batch returned. The work of levelling up the ground between the sheds and slipway is making good progress.

The Aeroplane – May 21, 1914.

On Tuesday, at Dundee, Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., with A.M. Fitall, on Short 75 (100-h.p. Gnome), flew over the Tay. On his return to the slipway, Capt. Kilner, who has lately been transferred to this station, took charge, and with A.M. Hamilton flew up the Tay. Coming back with the wind, he was flying at 90 miles per hour, but had a stiff fight facing it. On Thursday, on the same machine. Major Gordon, with Chief A.M. Russell, made a test flight to the Tay Bridge and back.

As he descended, Capt. Kilner, with. C.A.M. Usher, set out on Short 74 for the Tay Bridge. He turned and came back down the river, and as he passed the base. Major Gordon rose on No. 75 and both machines flew down the Tay and round the coast to St. Andrews, returning after a stop of about an hour. After landing, the pilots exchanged machines and gave a good display of banking.

The Aeroplane – May 28, 1914.

The pilots at Dundee have been almost every day during the past week up and down the Tay.

Good flying was seen in the gusty wind of Tuesday when Major Gordon, R. M.L.I. (Short No. 74), and Capt. Kilner, R. M.L.I. (Short No. 75), were out. Capt. Kilner was first away and made a circular flight over the district for 40 minutes. Major Gordon was only up half that time and did not go far, the conditions being too “bumpy” for long flights.

On Saturday the officers made three good flights. Major Gordon was first out in Short No. 77, accompanied by A.M. Colman for about 15 minutes, followed by Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I., who took C.A.M. Dickenson. Some engine trouble ensued and they came down alongside the German cruiser “Augsburg,” which was lying off the air station. After adjustment the machine went up the river for another turn. The third flight of some 15 minutes was made by the same officer with Mr. Mclntyre as observer.

The Aeroplane – June 4, 1914.

The officers at the Dundee Base were out on Monday forenoon. The machines used were Shorts (100-h.p. Gnomes), Nos. 74 and 75. Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., on No. 74 with A.M. Hamilton and Capt. Kilner, R.M.L.I., with C.A.M. Usher on No. 75 flew north for Aberdeen. A descent was made at Stonehaven for about five minutes, Aberdeen being reached in seventy-five minutes from Dundee, where Capt. Kilner had one of his floats punctured by some wreckage. This was put right with the help of some fishermen, and the return to Dundee was commenced at 2.30 p.m. and the pilots landed an hour and a half later.

On Tuesday morning flying was started early and a lot of practice work with submarines was done. At 10.30 Major Gordon went off in Short No. 74 with Lieut. Rendall and C.A.M. Shaw as passengers to look for submarines at the mouth of the Tay for over an hour. Capt. Kilner with Lieut. Bonham-Carter as passenger on Short 77 flew out to the scene of operations. A descent was made in the open sea, and as the passenger was restarting the engine it backfired and the starting handle was jerked overboard. The destroyer “Ettrick” took the seaplane in tow and brought her back to Carolina Port Later Major Gordon again flew Short No. 74 with A.M. Walker, and after circling St. Andrews flew up the Tay to Newburgh, where a short stay was made and Capt. Kilner made two flights in No. 77, carrying A.M. Willburn and Lieut. Randall as passengers.

On Thursday Major Gordon set off for St. .Andrews on Short No. 74 with Lieut. Curtiss, R.N. Capt. Kilner had some trouble in getting the required “revs” out of his Gnome, but at the second attempt gave a long display of good flying east of Broughty Ferry. No more flying was done during the week.

Surveyors have been busy during the past week or two at the Carolina Port, and it is learned that an improved concrete slipway will shortly be commenced and also a large permanent shed, a workshop and a petrol store and a first-aid room. These completed, the base will assume proportions worthy of the importance of the station.

The Aeroplane – June 11, 1914.

On Tuesday several flights were made with the Short machines at Dundee. Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.L, made two flights and Capt. Kilner, R.M.L.L, one on No. 77 (100-h.p. Gnome), an air-mechanic being carried on each occasion. The flights were all over the district and at 1,000 to 2,000 ft. On Thursday, Capt. Barnby, with an air-mechanic, flew to St. Andrews on Short 77 and was accompanied by Capt. Kilner on Short 75, who carried Petty-Officer Chidgey as passenger. On the return journey, when entering the mouth of the Tay, a tongue of flame leaped from the engine of No. 75 and scorched the passenger’s face. It was immediately shut off and the machine planed down to the water, where it was discovered that one of the valves was “sticky.” Capt. Barnby also descended to see what was the matter, and he hailed a passing tug, which took No. 75 in tow and brought her up to Broughty Ferry, where the launch from the base took her in charge. The injuries to the passenger were slight, owing to the rapid cutting out of the engine.

The Aeroplane – June 18, 1914

There has not been much flying at Dundee during the past week. On Thursday afternoon, at 3.30, Capt. Kilner, R.M.L.L, carrying Lieut. Johnstone, R.F.A., on Short No. 73 (100-h.p. Gnome), flew to Monifeith. Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.L, then made a flight on the same machine with Lieut. Boyd, R.G.A., giving a fine display of banking by the Tay Bridge. Capt. Kilner again took over the machine and, along with Private Oldfield, visited Monifeith and then, after circling the “Vulcan,” returned to the base.

With Lieut. Johnstone, R.F.A., as passenger, Capt. Barnby made another flight, circling the ferryboat. Engine trouble forced his return to the base. This was soon put right, and Capt. Kilner made the last flight for the day with A.M. Fisher, circling some torpedo-boats in the Tay. There was no more flying during the week.

The Aeroplane – June 25, 1914.

Flying commenced at Dundee on Tuesday of last week, when Capt. Barnby, R.M.L.I., left the base at 10.30 with Lieut. – Comdr. Layton, of the Submarine Service, on Short No. 77. Capt. Kilner, with Lieut. Taylor, on Short No. 75, followed, and both machines engaged in submarine “spotting” off the mouth of the Tay for an hour and a half. Capt. Barnby then made a second flight over Dundee.

On Wednesday, at 10.15, Capt. Barnby, on Short 74, carried Colonel Brown, while Capt. Kilner, on Short 75, took Lieut. General Sir J. S. Ewart, K.C.B., A.D.C., G.O.C. Scottish Command, and both machines flew for some time over the Tay Valley.

After landing those officers, the pilots took aboard A.M. McIntyre and A.M; Dickinson as observers, and flew to Barry Camp and observed the effects of big gun fire at sea targets. Capt. Barnby landed near the shore beside the camp, after which both machines returned to Carolina Port.

1st July 2014 – Formation of the Royal Naval Air Service

The big news of July 1914, apart from the belligerent rumblings from Europe, was the announcement of the creation of the Royal Naval Air Service as part of the Royal Navy, with the Royal Flying Corps focussing entirely on Army aviation.

This was to some extent a formal announcement of what had become the practical split between the Military and Naval Wings pf the RFC.

It would allow the Navy to concentrate on the development of seaplanes, and aircraft carriers both of which would have a role to play in the coming war.

August 1914 – War

The Aeroplane August 5th 1914 – War!

At this moment of writing it appears that this country is inevitably committed to take its part in the greatest war the world has ever seen. Thanks to the machinations of politicians who pose as statesmen the Powers find themselves grouped quite in the wrong way. Our alliance with France is as it should be, but that the two leading civilised nations should find themselves allied with Russia against Germany and Austria, is altogether unnatural. Servia thoroughly deserves all the thrashing she gets. The .Serb is an unlovely and unlovable beast, and has been so as long as history recalls, and it is utterly foolish that we should be called upon to waste men and money over what is Servia’s fault. The alliance with Russia is against all reason. “Scratch a Russian and you find a Tartar,” is an ancient proverb. Scratch a Tartar and you find a Chinaman is its logical sequel. The Slav is the real “Yellow Peril,” for the Slav is at bottom an Asiatic. Our alliance with Japan was an equally unnatural contract, but it was good diplomacy, for without it the Russo-Japanese war would never have taken place, and Russia would have been stronger than she is to-day. But for that war our Indian frontier would have been in greater danger than it is. If Russia comes out on top in this present war, does anyone think that her gratitude to us for our support will cause her to keep her hands off India when she can spare men from her German frontier? Those who know the Russo-Indian problem will remember the admonition of the old shikarri in Mr. Kipling’s famous allegory —”Make not your peace with Adamzad, the bear that walks like a man.”

However, nothing on God’s Earth can excuse Germany’s unprovoked attack on France, and we have got to see France through her trouble on that account. Quite probably, by the time these notes appear, an equally unprovoked attack will have been made on our own fleet, for already the Germans are holding up our merchantmen in German ports. A smashed Germany is not as good a bulwark against the advance of the Slav peoples as a solid Germany backed by France and Italy would be, but perhaps a smashed Germany may be less dangerous than a top-heavy Germany ready to fall at any moment on us and our friends the French. Therefore, in the name of common sense let us have at it, and smash Germany thoroughly, once and for all.

Germany is built up of many incompatible elements, the Schleswiger is a Dane, and quite a good chap. The Alsatian is a Frenchman and hates Germany. The Bavarian is a peace-loving, hard-working, decent poor soui), and cordially dislikes his Prussian master. And the Pole is nothing in particular, and loathes German, Russian, and .Austrian with beautiful impartiality. The German Empire dissolved into its component parts may still be a useful barrier, and not a danger. It is Prussia, as usual, who is making a beast of herself, and it is Prussia rather than Germany whom we have to fight. Of course, our cause is an unjust one, but that makes no difference. To quote the cynic’s .verse:-

“Thrice armed is he who hath his quarrel just,

But more so he who gets his blow in fust.”

If those who misgovern us have any sense left, our First Fleet should by now have bottled up the mouth of the Kiel Canal. If it has not been done then the German Fleet is now loose in the North Sea, and our food supplies are not as secure as they ought to be. As Napoleon said, “The Lord is on the side of the big battalions,” and our immediate duty is to see that the French Army is augmented by our whole Expeditionary Force. It only amounts to the strength of about one Army Corps of any Continental Power, but it is splendidly organised and equipped, and should account for more than its weight of any other army. With it will go the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, which, considering its small size, is probably the most efficient force of its kind in the world.

The Equipment of the R.F.C.

Since Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson has had a free hand with the R.F.C. enormous strides have been made with its equipment, but he has not been able to accomplish the impossible. The smallness of the R.F.C. is due primarily to the obstinacy of the previous controllers of the War Office who did their best to discourage the production of aircraft—despite the efforts of Colonel Capper, R.E.—and, secondarily, to the dog-in-the-manger policy of the Royal Aircraft Factory, who succeeded only too well in squeezing out promising firms of aeroplane makers, and in holding back the development of others. It is also entirely the fault of the R.A.F. that we have practically no British aero engines. Both aeroplanes and engines were “crabbed” in every possible way, so that their development might be delayed until the R.A.F.’s own products were nearer to being fit for use. The R.A.F. tractor biplanes, “B.E’.s” and “R.E.s,” have proved successful as flying machines—though constructionally defective — but the R.A.F. engine has been a dismal failure, consequently, we can produce aeroplanes, which can be built in a month or so, but we have hardly any engines—a position aggravated by the fact that it takes as many months to make an engine as it does weeks to make an aeroplane.

Such engines as we have are all of foreign make. There is not one British-built engine in use by the R.F.C. Even those firms who are building engines in this country to foreign design have had to obtain certain of their materials abroad. Truly, a pretty state of affairs, and one for which the R.A.F. is absolutely, solely, and entirely to blame.

The question is whether we have enough spare engines in the country to make good the wastage of war. The R.F.C. has a small stock of spare engines, but, thanks to lack of official encouragement, civilian flying is in such a bad way that there are only a few low-powered engines in the country apart from those owned by the Government.

I suggest to the War Office that its wisest course is to send out orders at once for a number of single-seater “scouts” with 50-hp Gnomes to firms like the Bristol and Sopwith Cos, and if those firms are too busy to turn the machines out now, let them sub-let the contracts to smaller firms like Blackburn, the Eastbourne Co., the Perry Co., the Hamble River, Luke and Co., and any others they can discover.

With 50-hp Gnomes these little scouts will do well over 65 m.p.h., and the engines would be far more useful in this way than if the Army bought up old school box-kites and tried to use them. Such 8o-h.p. Gnomes as are available should be commandeered and used for machines of proved value such as the 80-h.p. .Avros, Sopwiths, and Bristols. Firms like Vickers Ltd., the Grahame-White Co., Armstrong-Whitworths, and Handley Page, who are already at work on B.E.s, should be accelerated and supplied with ail the 70-h.p. Renaults out- of Maurice Farmans, and the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. should concentrate on Henri Farmans, unless their new tractor biplane is already approaching completion—when it is ready it can be accepted without question.

It is probable that quite a reasonable number of Beardmore-Daimler, Green, and Curtiss motors are nearly ready in the works, and these should be hurried forward and used for R.E.s by the R.A.F.—for perhaps in this national emergency even the staff of that institution will sink its jealousy of certain British products, and will do its best in the country’s service.

By concentrating the work of each firm on specific types large number of machines could be turned out in the next two months, and these machines would be equally valuable either for military work abroad or for coast patrols from the Naval Air Stations.

The Navy’s Affair.