First Air Raid of WWII – 16

14:27 – the first wave attacks, confusion reigns

| < 15 first confirmed sighting | Δ Index | 17 Sink the Hood! > |

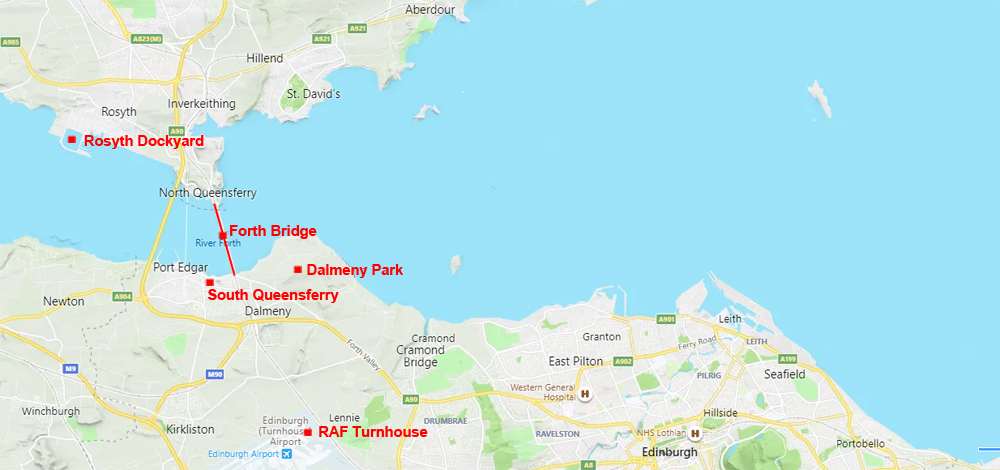

At 14.27 hours the anti-aircraft battery (RSG 1), situated in Dalmeny Park, to the west of Edinburgh, had been busy practising loading (blanks) when the battery commander reported (having accurately identified) three Junkers Ju88s flying up the Forth at an altitude of 10,000 feet. ARP Wardens in South Queensferry watched the aircraft circling overhead.

No warning or alarm had been received up to that moment. At 14.30 Blue Section 602 Squadron, reported that apart from having seen a section of Spitfires landing at Drem (Red Section returning from patrol over Crail) they had seen nothing. At that moment George Pinkerton’s RT immediately crackled into life again with the voice of the Controller informing his section: ‘Enemy aircraft bombing Rosyth, patrol five miles north of present position.

At the same time the battery commander in Dalmeny Park reported seeing the aircraft over the Forth Bridge. Naturally keen to open fire, he was not given the order to do so for a further 11 minutes when reports were received that the Forth Bridge was being bombed. Three minutes after the first bombs had been dropped the battery crew were finally given permission to open fire and the only air raid sirens to sound were in military establishments. No sirens mounted in public areas were sounded during the German raid. The delay provides a further insight into the confusion and indecision which reigned at the time.

That morning Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding and his staff at Fighter Command HQ, Bentley Priory, had watched the continuation tracks of the enemy force develop as information from the RDF chain came in. He knew that once the enemy force had flown over the coast and inland, tracking the enemy was more problematic. In referring to the lack of air raid warning, Hugh Barkla, who was also at HQ Fighter Command, stated:

“What went wrong was due to an over-reaction to a series of false alarms. The allocation of ‘hostile’ identification to a track had been too lightly made, and the subsequent despatch of fighters to intercept had risked there being a shortage of fighters ready to deal with genuine raiders.

The authority to name a track ‘hostile’ was then restricted to too small a number of Controllers. With improvements in communications and in procedure in Movement Liaison, the number of unidentified tracks decreased, and the accuracy of identification of hostiles improved. It would have been remarkable if such a novel and complex system had not suffered some such swings.

I have always believed that it was entirely due to the C-in-C over-ruling the statutory procedure and taking on himself alone the decision on whether the radar tracks were to be given the identification ‘hostile’.

The junior officers and the scientists in the Fighter Command Filter Room at the time were in no doubt but Sir Hugh Dowding incomprehensibly, held back. Fortunately, the consequences were not serious, though earlier warning to the fighters might have enabled them to shoot down more bombers.

The official records may have drawn a discreet veil over the C-in-C’s aberration . . . but the last thing that any of us would have wished was to record anything unfavourable to Lord Dowding. It was thanks to him that scientists were at HQFC in the first place, and it was he who widened our belief to cover all aspects of operational decision making.

| < 15 first confirmed sighting | Δ Index | 17 Sink the Hood! > |

top of page