First Air Raid of WWII – 6

11.00 to 14:00 eyes peeled for further intruders

| < 5 a 2nd Heinkel escapes | Δ Index | 7 The role of radar > |

As lunchtime approached the aerial activity lessened and apart from standing patrols, the 602 Spitfires were recalled and refuelled.

Both sections of A Flight had carried out search patrols, both reporting an above average amount of ‘chit-chat’ over the R/ T. Several pilots had instinctively felt that the action had been a precursor to something more serious. In fact, indications of enemy activity continued throughout the remainder of the morning of 16 October through both intercepted radio traffic and occasional sightings of high-flying aircraft.

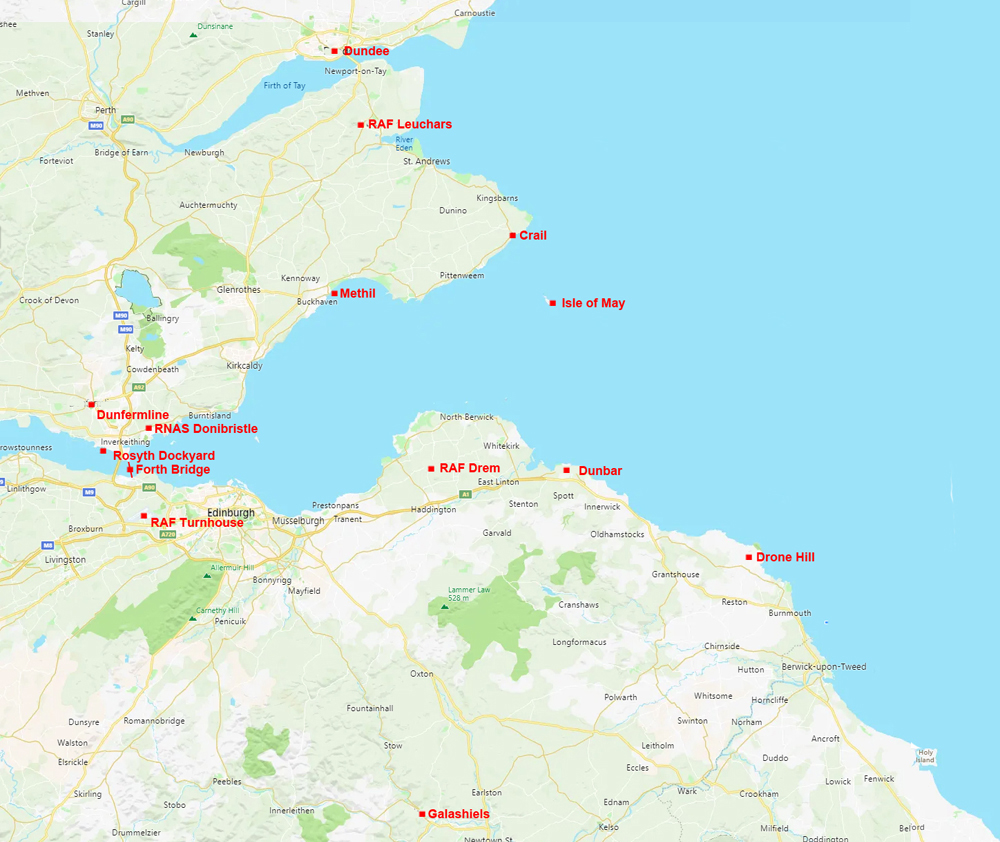

In the operations room at Turnhouse, S/L Bob Johnstone sat with his eyes glued on the ‘ops table’. On his left sat Flight Lieutenant Tommy (Tiger) Waitt, the senior operations ‘B’ officer who had before him a telephone and switchboard through which he had direct contact with the squadron control officers at 602 and 603 Squadrons at Drem and Turnhouse respectively. As Tommy Waitt studied the operations room map he relayed his orders to the squadrons through Bob Johnstone but not before he had jotted his instructions down on paper which were then passed to the controller for initialling before being sent to the teleprinter for transmission and filing at 13 Group Fighter Command HQ in Newcastle.

As air activity on the morning of the 16th began to develop it was by this means that the Air Officer Commanding (AOC Scotland and Northern Ireland) 13 Group, Air Vice-Marshal Richard Saul was kept informed. Through his direct telephone line to Bob Johnstone he himself would later become involved in the action.

Bob Johnstone had the responsibility of making the tactical decision of which squadron should be deployed, and how many aircraft should be sent up to intercept the enemy or patrol the airspace over potential targets, in order to maintain control over and maximise the use of his resources.

His fighter resources were valuable and had to be used prudently, he also had information before him which would indicate if the aircraft were being refuelled and rearmed and therefore vulnerable to attack.

Having directed Spitfires of 602 and 603 to intercept the incoming enemy aircraft Bob Johnstone provided vectoring until the pilots made a visual sighting of the German aircraft. They would then dispense with his services.

Fighter control and radio communication provided Johnstone with the opportunity to introduce tactical updates if another enemy force appeared to be heading unopposed towards a specific target.

At 11.00 hours Green Section of A Flight 602 Squadron, consisting of the CO Squadron Leader Douglas Farquar along with Flight Lieutenant Sandy Johnstone and Flying Officer !an Ferguson, were ordered to patrol the airspace over May Island.

From May Island the three Spitfires headed north towards Dundee and the Firth of Tay. With the insistence of the controllers that enemy aircraft were in the area the three pilots searched the heavens for bogeys, praying to be the first in action.

During the patrol Farquar’s radio went unserviceable and Sandy Johnstone took over leadership of the section. Following a report of unidentified aircraft in the vicinity of Drem, at 11.22 Green Section were ordered to ‘investigate, if you think necessary’, suggesting some doubt on the part of the Turnhouse controllers.

In response. Green Section continued their search northwards in what was a strong south westerly wind and good visibility but saw nothing but sea, sky and cloud. Sandy Johnstone felt that there was something out there but it was like searching for a needle in the proverbial haystack. In all probability, he felt that it was likely that the enemy were coming, but towards Edinburgh and not targets in the south.

With the section getting low on fuel and frustrated at their lack of success, the pilots were ordered to return to Drem.

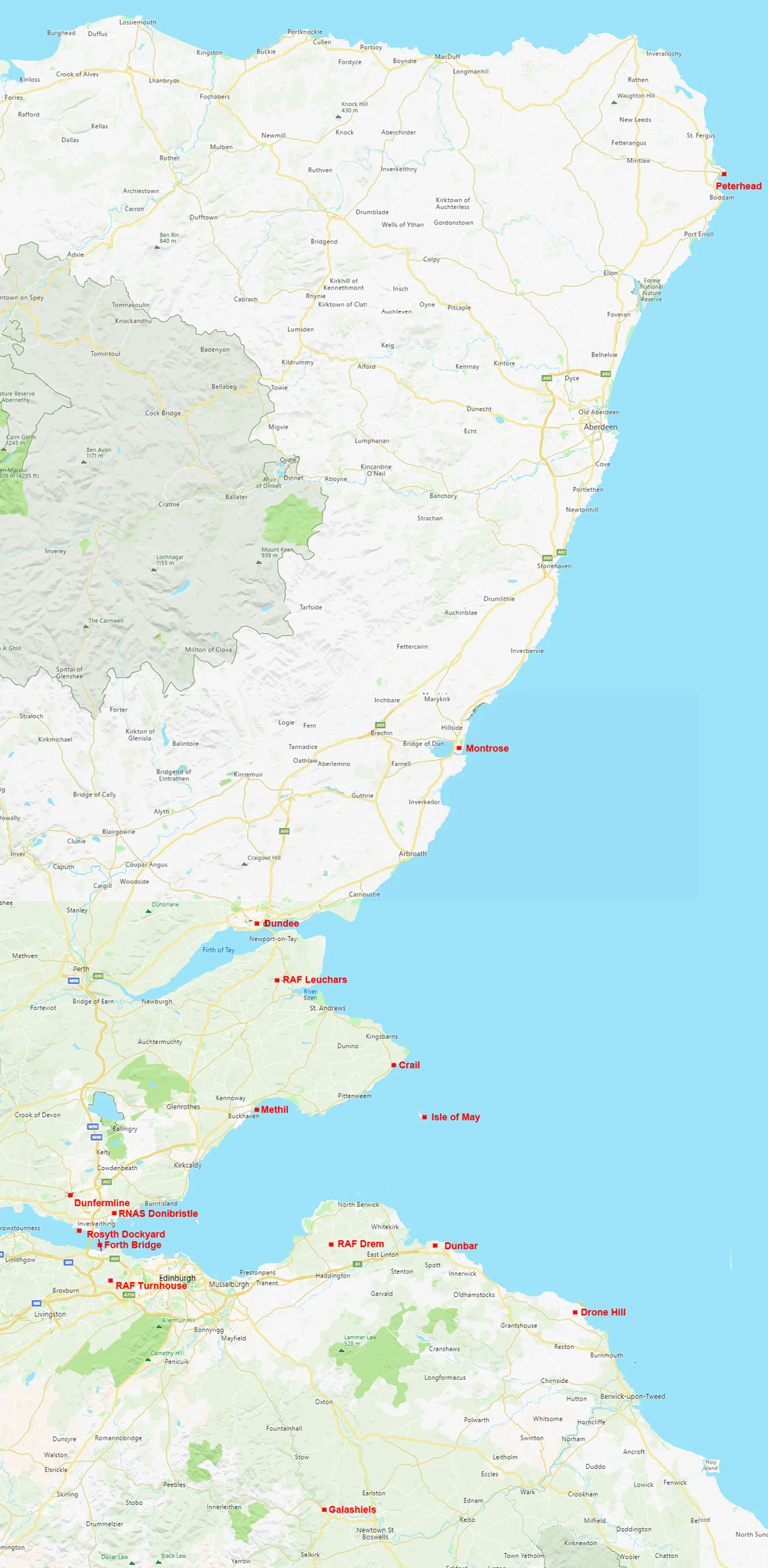

By this time they had drifted about 40 miles east of Peterhead and having been airborne for more than an hour and a half their fuel levels were critically low.

Sandy Johnstone recalled that ‘ … Drem was beyond our prudent endurance so I brought the boys into Leuchars to refuel, in spite of Drem being visible in the distance.’ At most they had 15 minutes flying time remaining and with little chance of making their own airfield, the Coastal Command airfield at Leuchars was a better option. On landing, the ground crews, used to working on Lockheed Hudsons, re-fuelled the Spitfires while Douglas Farquar telephoned Drem to report their whereabouts and to get permission to take lunch in the officers’ mess.

The morning’s activities continued when at 11.39 hours George Pinkerton led McKellar and Webb of Blue Section on another patrol from Drem. On this occasion they were ordered to patrol the airspace over St Abbs Head (near to Drone Hill RDF Station), a rocky outcrop of coastline just north of Eyemouth. The patrol landed back at Drem at 12.43 hours, the pilots having sighted no enemy aircraft.

The operations room at Turnhouse received regular reports of sightings throughout the morning of the 16th and 602 was called upon to intercept in favour of 603 because they were based at the airfield from which the earliest interception could be mounted and as a result they had at least one section airborne for most of this time. The Turnhouse controllers became increasingly concerned as reports of sightings of enemy aircraft came in not just from the Observer Corps but also the antiaircraft batteries whose aircraft recognition skills were not so reliable.

Airborne traffic in the Forth area also included a number of Sea Skuas from HMS Merlin carrying out training flights out of Royal Navy Air Station (RNAS) Donibristle. These plots made matters worse as they were often mistaken for enemy aircraft. After a while the number of reports of unidentified aircraft increased beyond the capability of the limited fighter resources which couldn’t possibly respond to them all.

| < 5 a 2nd Heinkel escapes | Δ Index | 7 The role of radar > |

top of page