Military Sites around North Queensferry

Introduction and background

Early History

For centuries, there have been Military Sites along the Forth. In the 1600’s the local defences included, “a battery of 16 cannon on Inchgarvie island plus the defences of North Queensferry itself – 12 cannon on the Ferry Hills, 5 cannon in the Fort, and an armed guard-ship in the sheltered waters of St Margaret’s Hope.”

The 12 cannon on the Ferry Hills were probably close to the site of Carlingnose Battery, with a commanding view of the Queensferry Crossing, and an overlapping field of fire with the battery on Inchgarvie.

Several cannon were captured by Oliver Cromwell’s sea-borne invasion forces which landed around the peninsula on Wednesday 16th July 1651. Some of the guns were dragged to Gallow Bank, to protect Cromwell’s troops from the Scots Army approaching from the direction of Dunfermline. Cromwell’s troops dug-in on the Ferry Hills as more reinforcements arrived.

The Battle of Inverkeithing was fought on Sunday 20th July 1651 between Cromwell’s troops on the North side of the Ferry Hills and the Scots on the slopes of Muckle Hill and Whinney Hill. The initial engagements took place around Ferrytoll. The Scots were forced to withdraw to the north, resulting is a trail of slaughter all the way to Pitreavie.

There is an explanatory panel on the wall of the waiting room at Ferrytoll Park and Ride.

It is recorded that Cromwell’s troops damaged some of the properties in the village, most notably St James’s Chapel. There are no visible remains from the time of battle but the whole peninsula can be considered as a military site from that time.

The Ness Batteries

In the aftermath of the incursion by John Paul Jones’s squadron into the Forth in 1779, the battery was reinstated on the point of the East Ness and a second battery was built on top of Castle Hill (later Battery Hill). There were about 20 guns in total – all 20 pounders – between the two batteries.

The lower battery, known as ‘Ness Battery’ was located just above sea level, at the point itself and appears to have been the main battery.

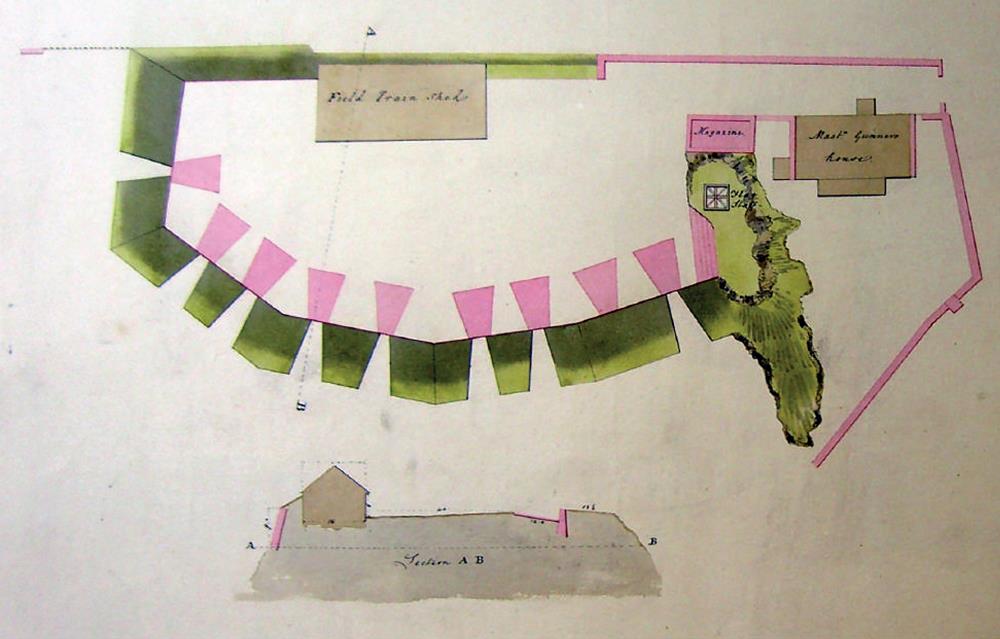

A plan of the Ness Battery in 1812 shows embrasures for nine guns, Field Train Shed, Flag Staff and Master Gunner’s house.

Great Britain eventually recognize U.S. independence in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, however a war with France now seemed likely, so the batteries were retained with repair work carried out in 1793, 1795 and 1798.

On 3 March 1797, 32 boatmen and other inhabitants of North Queensferry wrote to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, that, having been informed of the threat of a foreign invasion, they offered themselves in defence of the King, country and constitution, for service at the North Ferry Battery, Inchgarvie, or Inchcolm.

Their letter was forwarded to Lord Adam Gordon, Commander of the Forces, who duly wrote back accepting their offer which did ‘them much credit and will accordingly be acknowledged in the newspapers.’ Impressed by the selflessness of these men, Sir Walter Scott wrote to them, thanking them for their patriotic action in coming forward as volunteers for the defence of their country.

The Queensferry Volunteers were disbanded in 1802, after the Treaty of Amiens. However they reformed when war broke out again in 1803. Captain Ross received his commission on 25 June 1803 and formed the Royal Queensferry Artillery Volunteers to re-man the batteries at Battery Hill, Inchgarvie and Inchcolm. They were still active in 1812, and further repairs were carried out in 1814.

In 1817 the Board of Ordnance ordered that the batteries should be dismantled, although the guns remained on skids, and the battery grounds were retained with further repairs in 1823.

The property was eventually advertised to let in 1835 with the proviso that the government could re-occupy it: ‘The ordnance property of North Queensferry Battery consisting of a house and some pasture land, with a range of wooden sheds, which are not to be taken down, and will be let … on the understanding that the premises may be resumed at any time by government when required for the public service.’

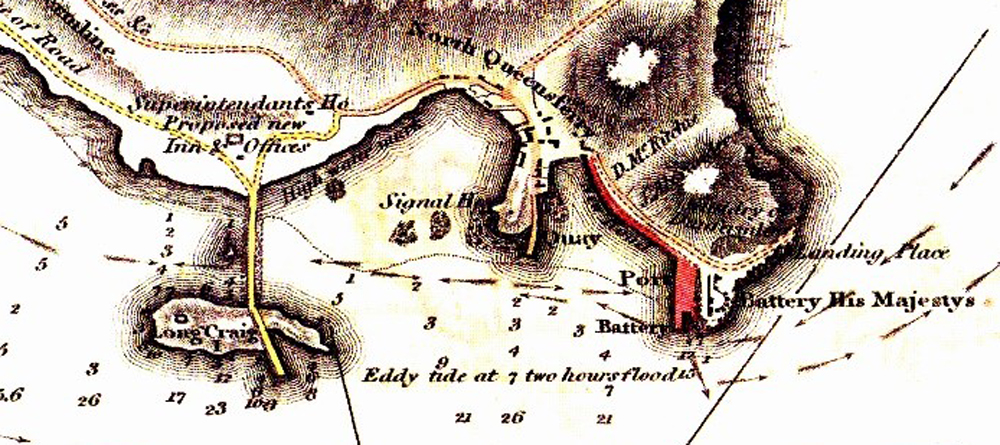

The Fort is shown in Rennie’s map of 1811 shows “Battery His Majestys” at the site of the future Forth Bridge foundations.

Extract from John Rennie’s map of 1811

Today, the caissons of the north section of the Forth Rail Bridge lie on the site, although some of the walling in the area may date from the battery’s life.

19th and 20th Century defences of the Forth

At the end of the 19th century, there was growing concern in Britain about the threat of war and the danger of attacks from invasion or raiding forces. The commercial ports in the Firth of Forth were considered to be potential targets which needed to be protected.

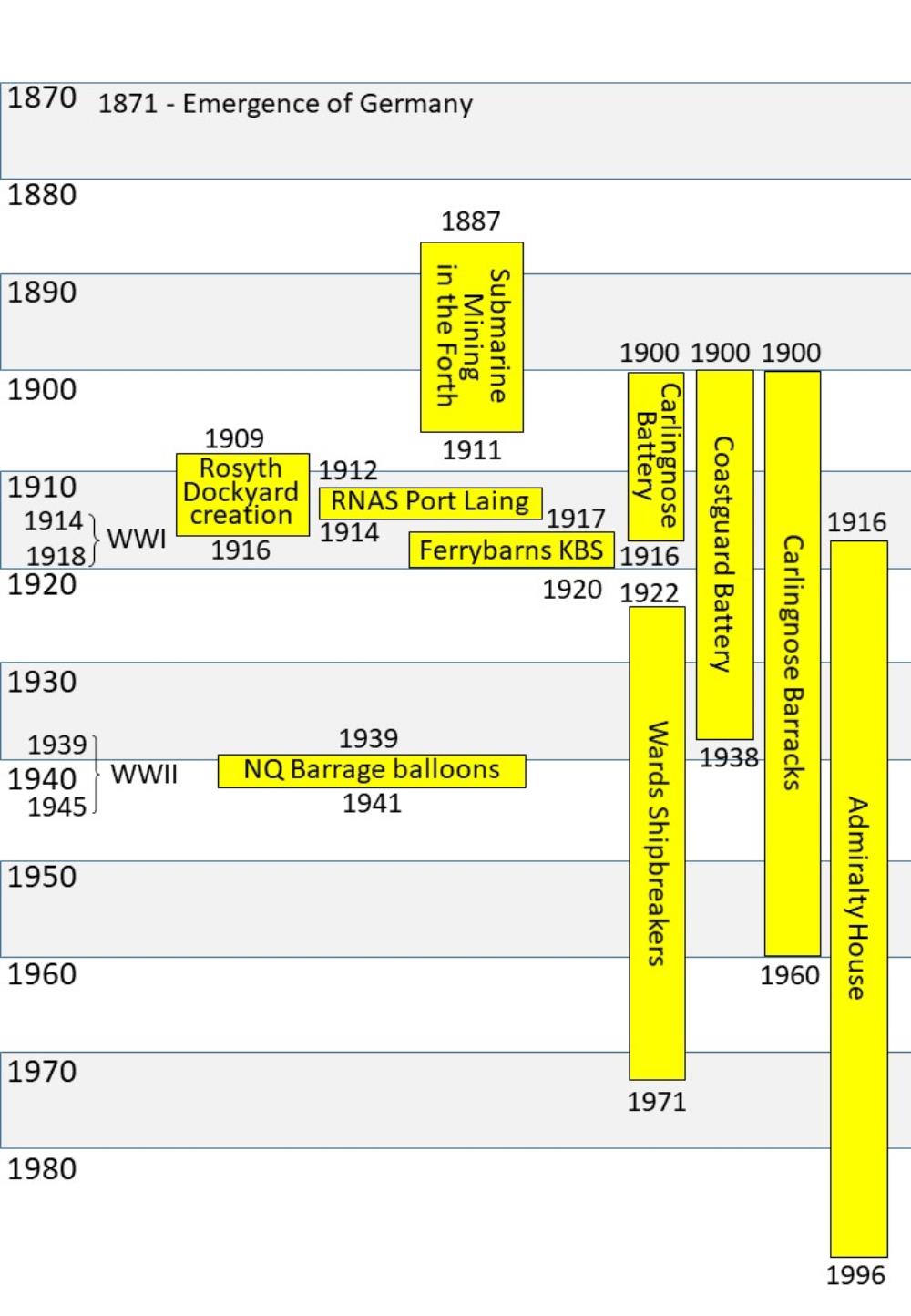

19th and 20th Century Military Sites Timeline

19th and 20th Century Military Sites Timeline

1887 – Submarine Mining in the Forth

The first step was the creation of a Submarine Mining Service in the Forth in 1887, initially based at Leith Fort with mines deployed from Inchkeith.

1900 – Submarine Mining at Port Laing

The service moved to a new permanent location at Port Laing in North Queensferry in 1900.

1902- Gun Batteries and Barracks in North Queensferry

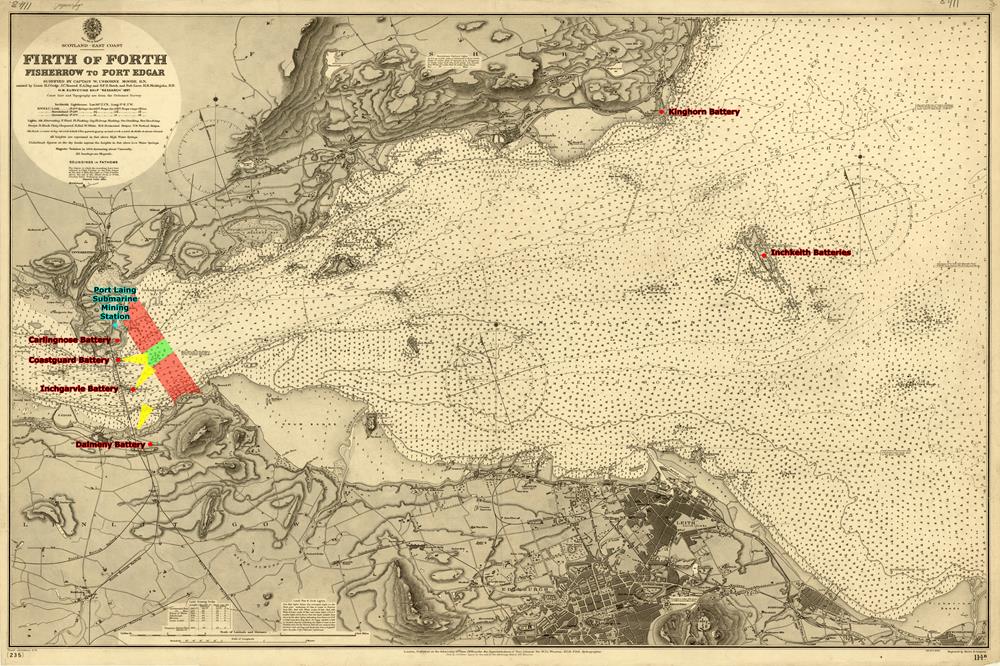

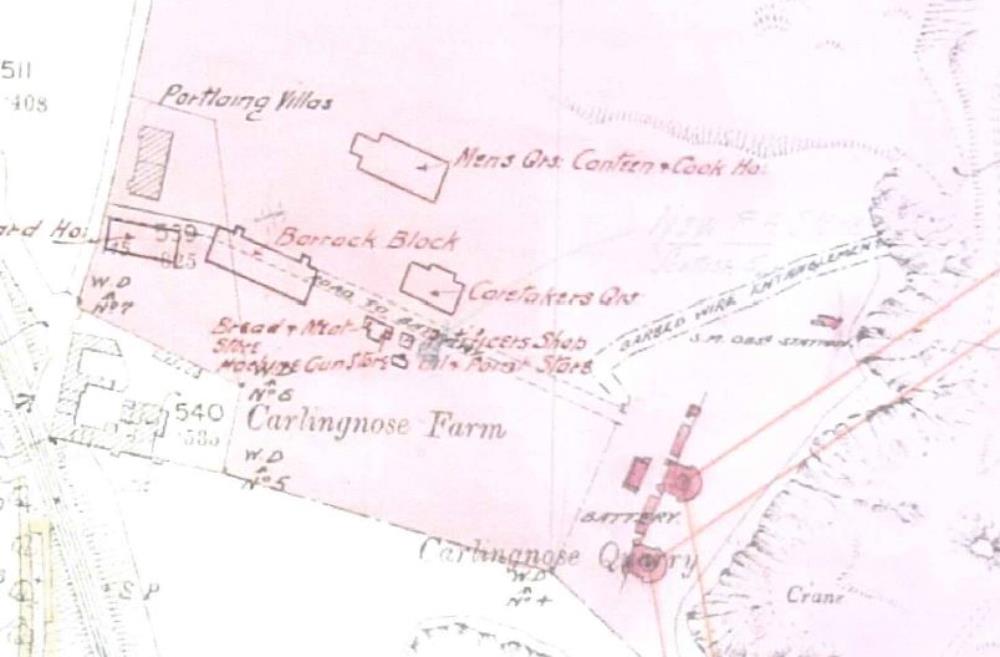

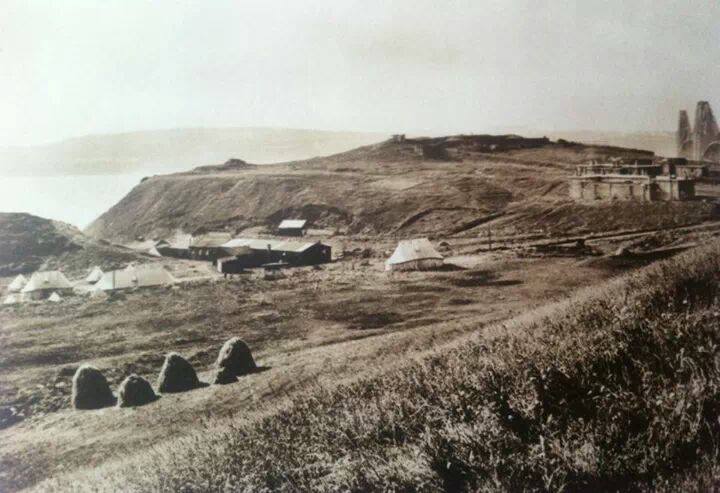

All Submarine Mining Stations were combined with associated gun batteries and searchlights. These were installed at Carlingnose and the Coastguard Station, on Inchgarvie and at Dalmeny in 1902.

Royal Engineers and Royal Garrison Artillery men and officers responsible for the guns and lights were housed at Carlingnose Barracks in North Queensferry.

Downstream, new batteries were built on Inchkeith, on top of the 19th century fortifications and at Kinghorn.

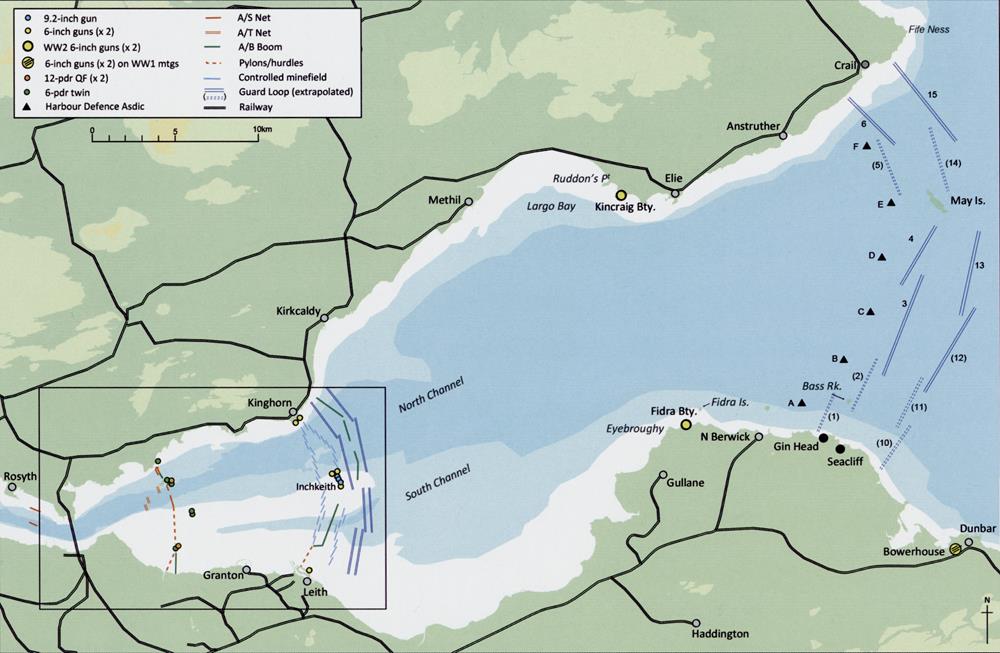

Forth Defences – 1901

Forth Defences – 1901

1903 – The announcement of Rosyth Dockyard.

The plan for the development of a Naval Dockyard at Rosyth was announced in 1903. The site was chosen to provide a North Sea base to counter the growing German High Seas Fleet based in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. Existing Royal Navy bases were on the south coast of England.

Political wrangling delayed the start of construction until 1909 with a planned completion date of 1916.

March 1905 – End of the Submarine Mining Service

The Committee of Imperial Defence, announced on 1 March 1905, that Submarine Mining would no longer form part of the Empire’s coast defences.

Rivalry between Royal Engineers and Royal Navy over who should provide Coastal Defences probably played a part in this decisions. A further factor in the decision was the increasing capability of submarines, which could slip unobserved through a friendly channel to wreak havoc in a seemingly protected haven.

Controlled mines would now become the responsibility of the Navy, who acquired all of the mines and equipment. The Royal Artillery took over the buildings at Port Laing.

1909 – Work begins at Rosyth, Carlingnose announced as artillery HQ to replace Leith Fort

In 1909, construction work on Rosyth Dockyard finally started. Progress on surveying the site and awarding construction contracts had been delayed by debates in Parliament. Work was expected to take seven years – i.e. completion was scheduled for 1916.

The construction would involve hundreds of labourers, on what was an uninhabited tract of land. Accommodation was urgently required. The problem was partly resolved when the Naval Base Mansions were built at Jamestown in 1909, with capacity for 600 labourers.

Several of the civil engineers from Easton Gibb & Son were housed in some of the larger houses in North Queensferry.

It was also announced that Carlingnose would replace Leith Fort as the headquarters of the artillery in Scotland. Accommodation was needed for two companies of the Royal Garrison Artillery (180 men) who would transfer from Leith. The site would also become a training ground for the Territorial Army.

1910 – Military Camp and exercises at Carlingnose

There were training activities across Fife and throughout Scotland in 1910, with the following at Carlingnose at various times during the year:

Royal Highlanders 6th Battalion

City of Edinburgh Fortress Company

Forth Company Royal Garrison Artillery

Black Watch (Territorial Army)

No 5 Company North Scottish Royal Garrison Artillery

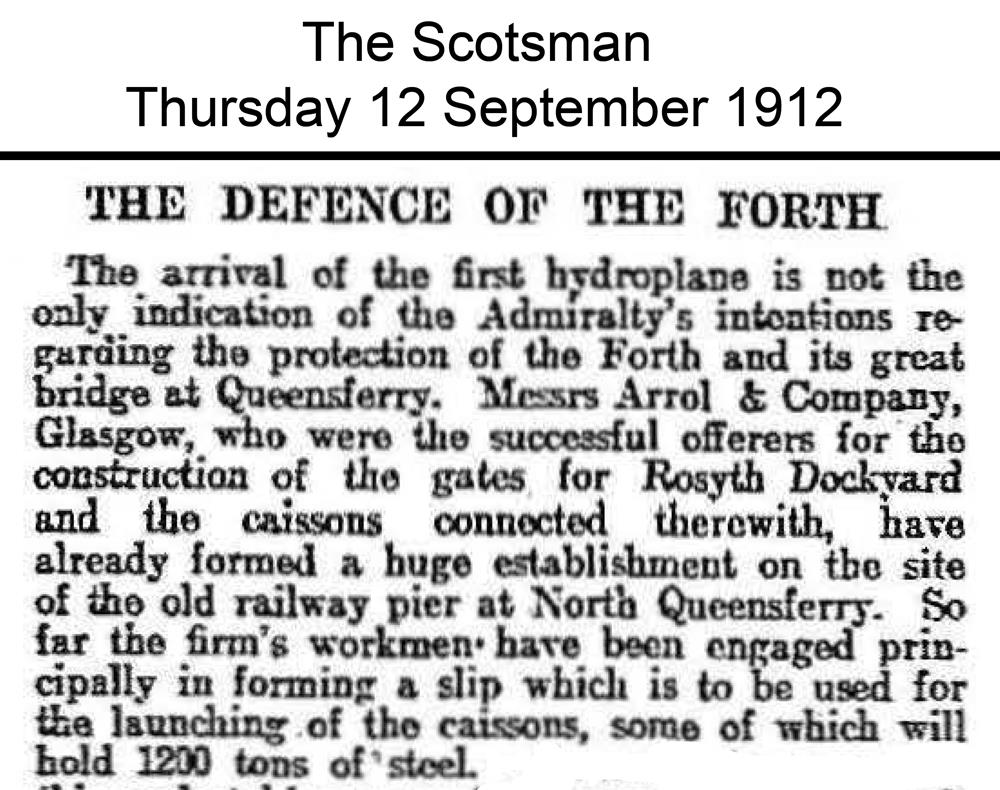

1911 – Rosyth Caissons constructed at the Railway Pier, North Queensferry

William Arrol and Co. of Forth Bridge fame were awarded the contract to supply the caissons (lock gates) and the basin sluices (water valves) for the Dockyard. There was limited construction space available at Rosyth – the entire site was submerged at high tide – so four of the massive caissons (they each weighed more than 900 tons) were built on slipways next to the Railway Pier, then launched and towed upstream to Rosyth.

These Caissons were manufactured on the Railway Pier before being launched and towed upstream to Rosyth.

Meantime training exercises continued at Carlingnose with No. 1 Company North Scottish Royal Garrison Artillery.

1912 – Compulsory purchase of houses at Carlingnose

The Scotsman reported:

“Houses in close proximity to the forts, constructed a number of years ago by the War Office authorities on a promontory at North Queensferry, have been acquired on behalf of the Government, and the occupiers have been compelled to remove forthwith. This is accepted in the neighbourhood as an indication to transfer the artillery from Leith Forts to North Queensferry earlier than was originally contemplated. On North Queensferry becoming the headquarters of the Forth Garrisons, about 200 men will be stationed there, and all the ports in the Forth will supervised from that point.”

These houses were probably Port Laing Villas.

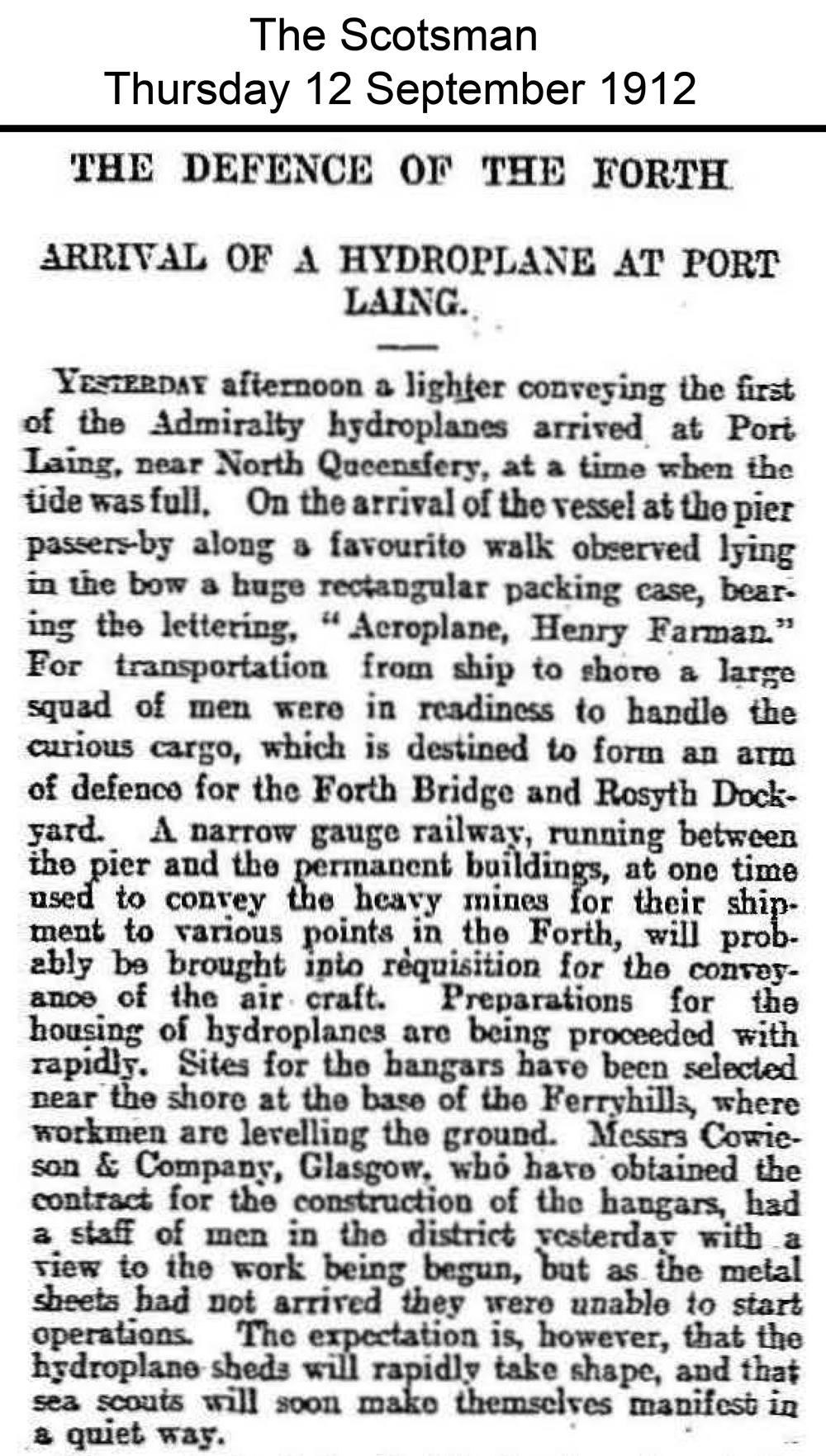

1912 – Military Aviation arrives in North Queensferry

On Thursday 12th September 1912 The Scotsman announced the creation of the first Military Air Station in Scotland – at Port Laing.

It was hoped that aerial observers could detect the wake of a submarine travelling underwater.

1913 – Completion of Castlandhill Radio Station; Land Defences at North Queensferry

Castlandhill radio station created to complement Rosyth Dockyard. It had a nominal range of 200 miles and was part of a national network of ship-to-shore stations.

Castlandhill radio station created to complement Rosyth Dockyard. It had a nominal range of 200 miles and was part of a national network of ship-to-shore stations.

The defences at North Queensferry were now an integral part of a wider set of defences protecting Rosyth Naval Base and Castlandhill Radio Station.

Anti-Submarine Nets were slung from the Forth Bridge and a comprehensive set of local defences – trenches, barbed wire entanglements, machine-gun posts and blockhouses – were installed, linked by a communications network of telephone landlines.

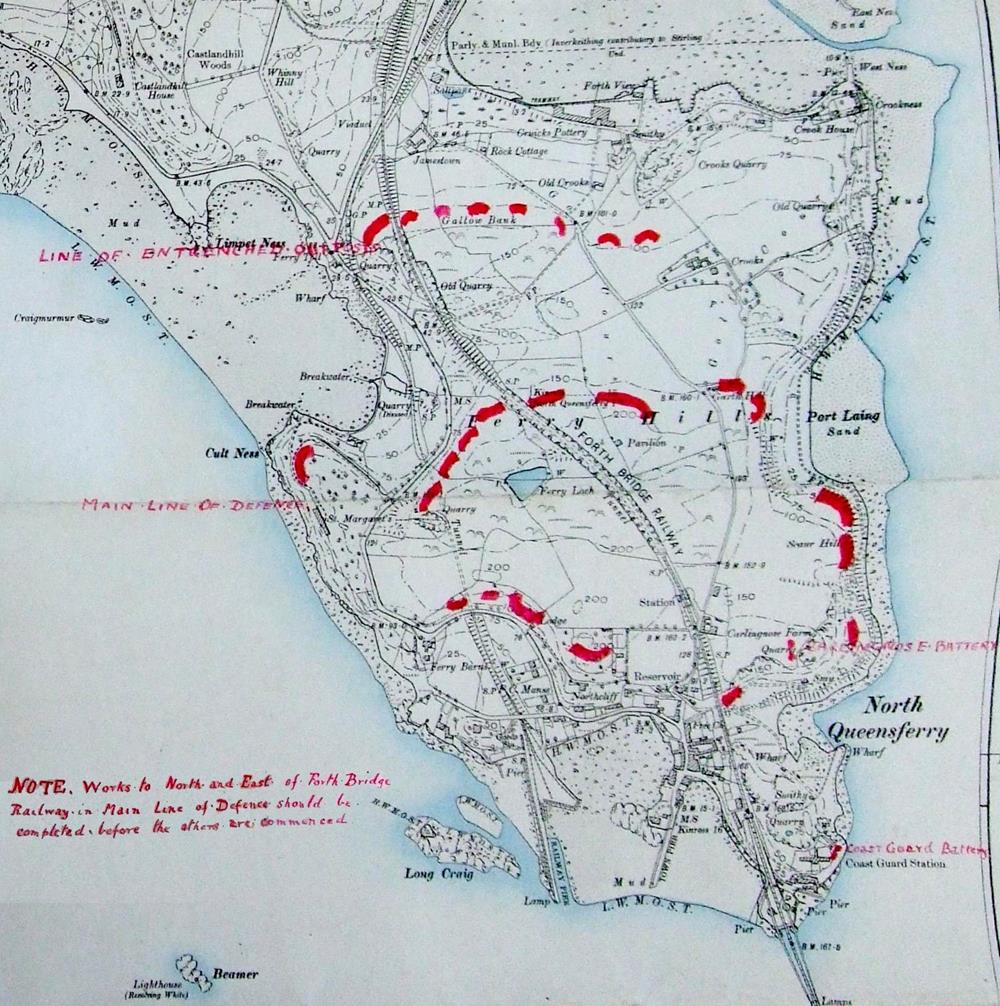

Map, dated 1916, showing the complex defences of the northern approaches to the Forth Bridge, integrated with those of the Castlandhill Naval Wireless Station.

Map, dated 1916, showing the complex defences of the northern approaches to the Forth Bridge, integrated with those of the Castlandhill Naval Wireless Station.

(Note “Arrols Huts” at the head of the Railway Pier – the site of Rosyth caisson construction.)

Trench lines round the village

This map shows where trenches were dug to impede any invaders. Some of them were dug across the golf course.

This map shows where trenches were dug to impede any invaders. Some of them were dug across the golf course.

1914 – Training exercises continued at Carlingnose

No. 6 Company Forth Royal Garrison Artillery

6th Black Watch Company

Nos. 1 & 4 (Edinburgh) Company Forth Royal Garrison Artillery

“The City of Edinburgh (Works) Company were engaged in the construction of various types of fire trenched with overhead cover, gun pits, barrel piers etc., and in practising demolitions and fougasses [land mines in which the charge is overlaid by stones or other missiles so placed as to be hurled in the desired direction] while a suspension bridge to carry infantry in file was erected over a valley 250 feet wide by 60 feet deep. . .they then proceeded to Inchkeith where they are engaged in constructing special works on the defences. Meantime the City of Edinburgh (Electric Light) Company practised on the searchlights at Carlingnose and Dalmeny.”

March 1914 – The Airstation at Port Laing moved to Dundee

While Port Laing was very close to the Grand Fleet at Rosyth, the conditions at Port Laing were not ideal. The foreshore proved to be sticky, making it difficult to recover planes after they had landed on the water, and the steep cliffs behind the beach would have cause lots of wind-shear, violent up-draughts and down-draughts, that would have affected the handling of the primitive aircraft.

A new Naval Airstation was under development at Carolina Port in Dundee, and in February 1914 orders were received to move from Port Laing to Dundee.

Another factor was the affection for flying displayed by Winston Churchill. He had flown in all types of military aircraft, taking control on several occasions. As he was the M.P. for Dundee, there is little doubt that he was influential in the move from the Forth to the Tay.

The final factor was the artist Charles Martin Hardie, the owner of Garth Hill in North Queensferry, who having leased the land at Port Laing to the Admiralty later tried to negotiate a steep increase in the rent.

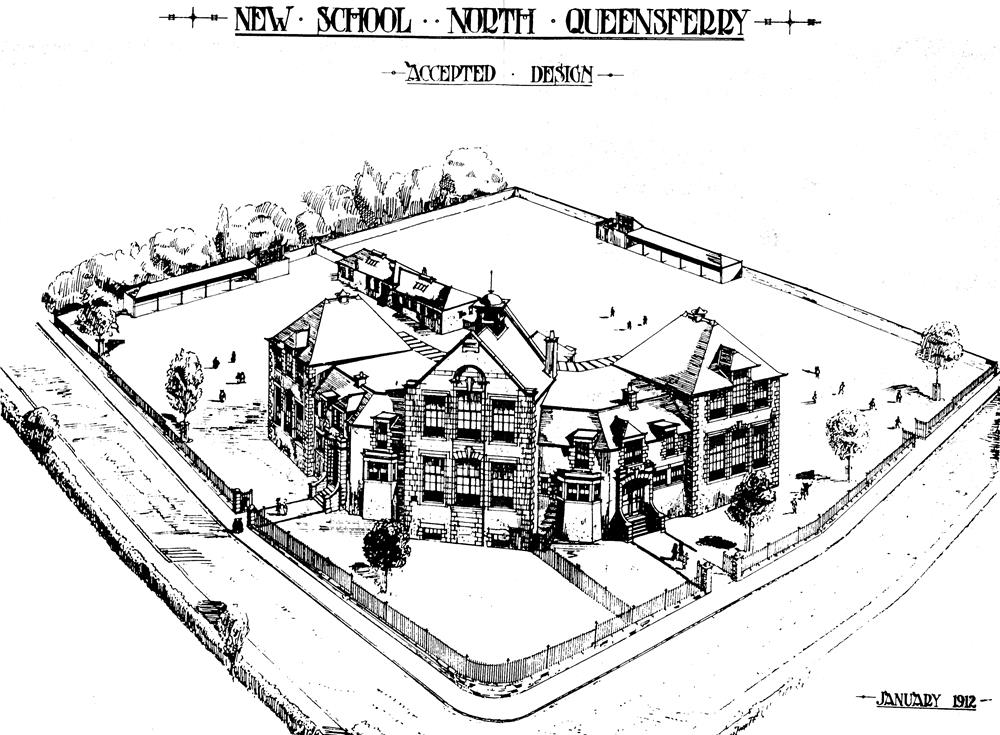

April 11th 1914 – The “new school” was formally opened.

The old school on the Brae was bursting at the seams with the growth in population following the construction of the Forth Bridge and then Rosyth Dockyard. A new school was approved in 1912.

Although the new school was formally opened in April 1914, it was not ready until 1st June 1914. It was only used for a few weeks before the summer vacation began on July 10th. 1914. A few weeks later, the country was at war.

1914 – August 1st – Germany declared war on Russia

1914 – August 3rd – Germany declared war on France.

German Troops implemented the Schlieffen Plan by marching into Belgium. Britain demanded that Germany withdrew from Belgium.

1914 – August 4th – Britain declared war on Germany.

The school summer vacation was extended until 31st August, and then for a further 2 weeks to clean the school and repair the damage caused by the school having been occupied by 6th (Perthshire) Battalion Royal Highlanders (Black Watch) during the holidays. School resumed on September 14th 1914.

Here is the full story of North Queensferry School – the war years – World War I

1914 – Rosyth Dockyard progress

The outbreak of war forced a change of plan in the construction of Rosyth Dockyard. The work was on schedule but nothing was usable, so work was reorganized to bring as many facilities into use as soon as possible. The submarine basin was completed almost immediately providing a basin and jetties for small craft from September 25th 1914.

1914 September – the sinking of HMS Pathfinder

At the beginning of September 1914, the German submarine U-21, ventured into the Firth of Forth, as far as the Carlingnose Battery. At one point the periscope was spotted and the battery opened fire but without success. Overnight the U-boat left the Forth. On the morning of 5 September, it spotted HMS Pathfinder on patrol near the Isle of May.

U-21 fired a torpedo, and despite evasive action from HMS Pathfinder, the torpedo struck the ship beneath the bridge. Pathfinder sank, dragging most of her crew down with her.

Loss of HMS PATHFINDER, September 5th 1914 by W. L. Wyllie 1920 © IWM ART 5721

Loss of HMS PATHFINDER, September 5th 1914 by W. L. Wyllie 1920 © IWM ART 5721

Later that month a German U-boat attacked and sank three obsolete Royal Navy cruisers, manned mainly by reservists. Approximately 1,450 sailors were killed and there was a public outcry in Britain at the losses. The sinking damaged the reputation of the Royal Navy, at a time when many countries were considering which side to support in the war.

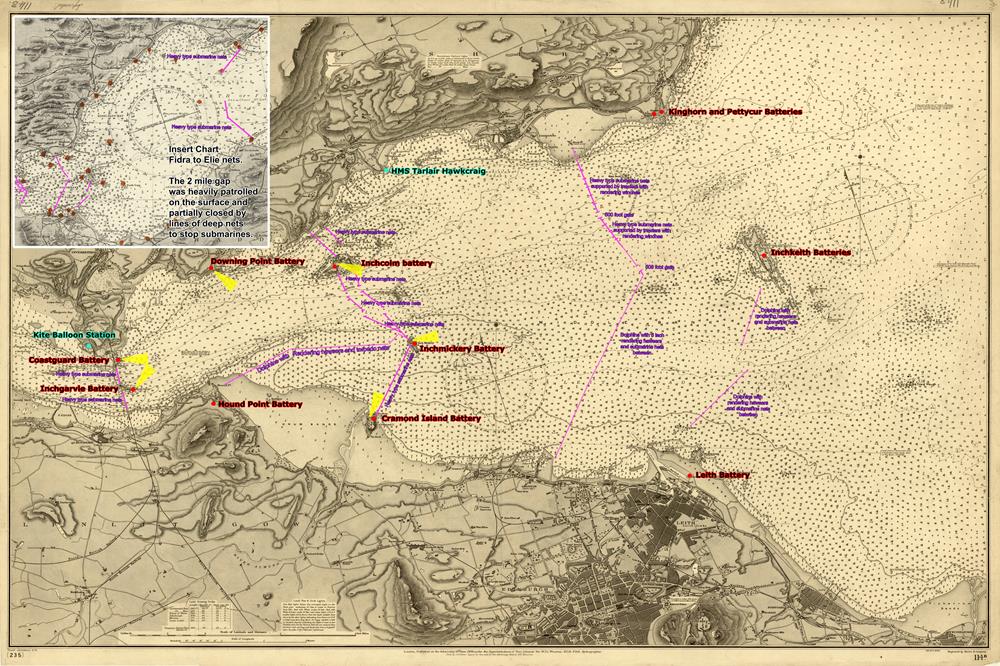

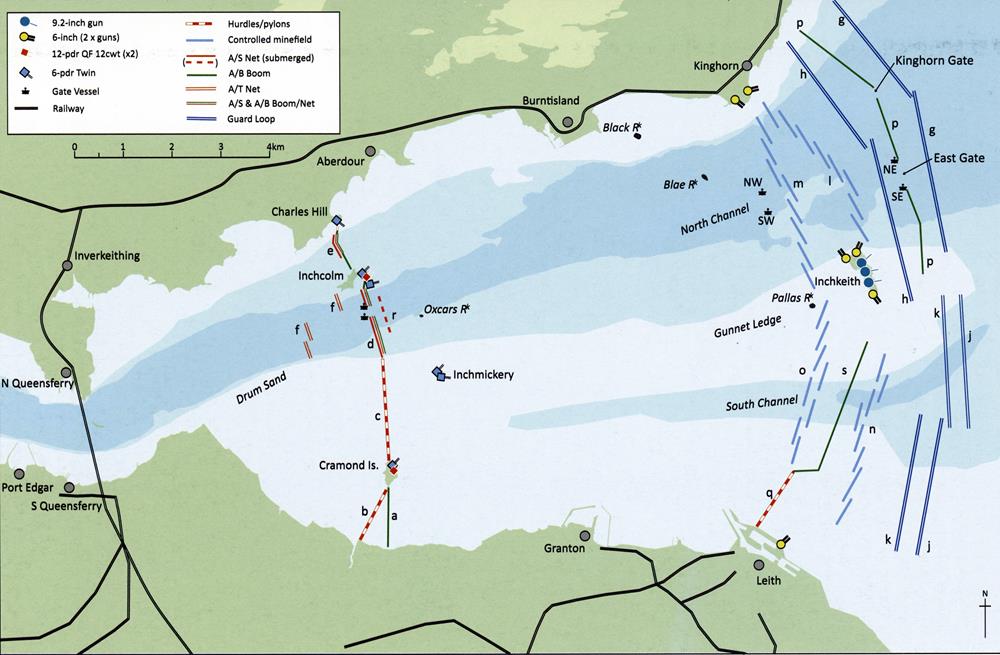

1914 October – Anti-submarine defences for the Forth

The 1908 proposals to provide gun batteries and anti-torpedo nets downstream of the Forth Bridge were revised at an October 1914 conference to discuss anti-submarine defences, and in late November, the Forth was closed to commercial traffic west of Oxcars to protect the anchorage and the Forth Bridge. The closure also prevented neutral shipping from entering to gather intelligence.

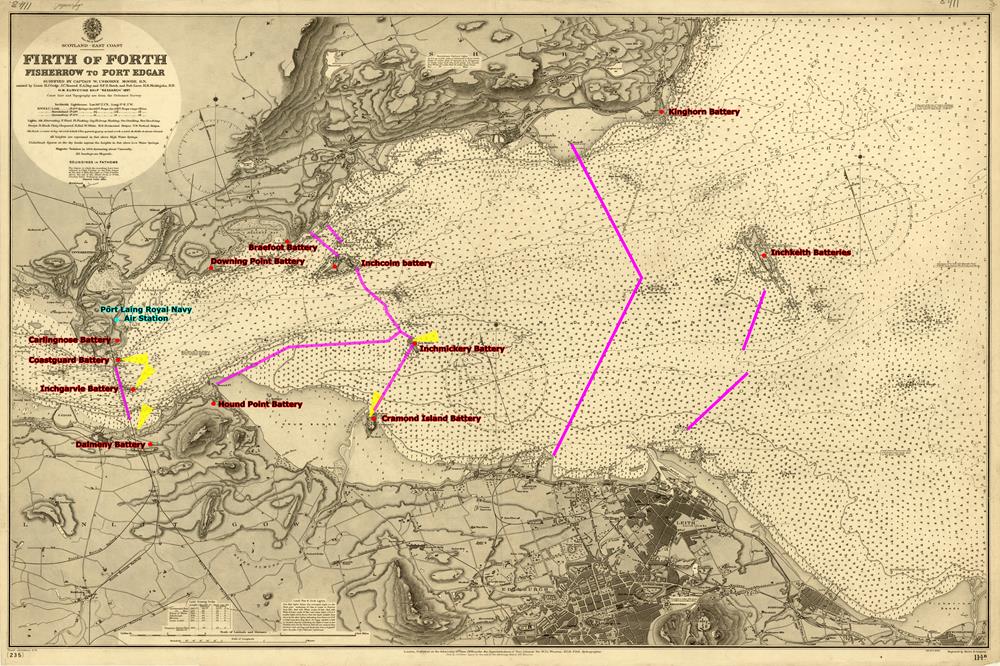

A Middle Line of defences at the line of islands, Cramond, Inchmickery and Inchcolm, was put in place, to supplement the existing Inner Defences, at the bridge, and the Outer Defences, on Inchkeith and at Kinghorn.

The Forth became the base for the Battle Cruisers of the Royal Navy; the Battleships remained at Scapa Flow.

Overall defences of the Forth in 1914

Overall defences of the Forth in 1914

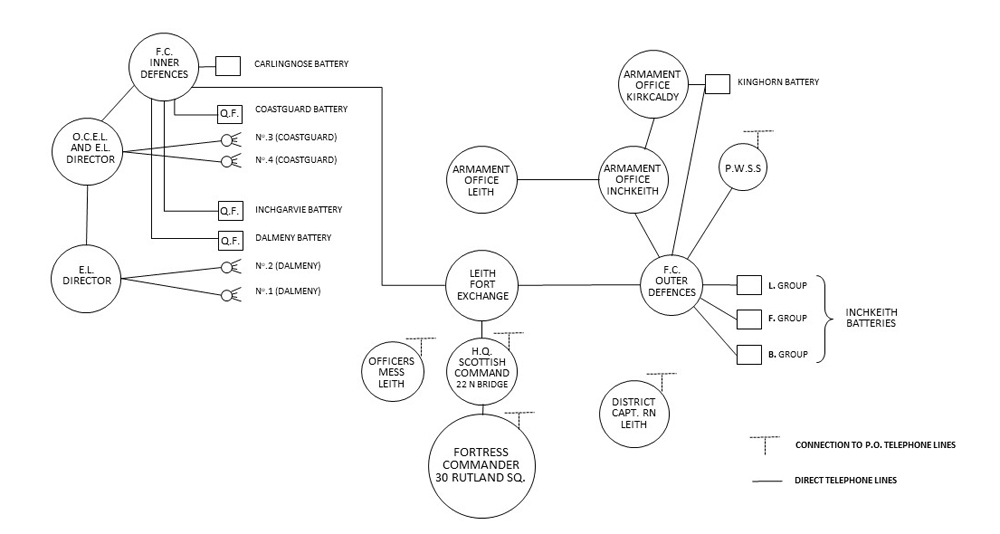

The gun batteries and electric light posts were linked by a combination of direct telephone lines and the public telephone network

Forth Defences – Skeleton Diagram of Command Communications – War Office 1909

1914 – Temporary Accommodation Huts at Carlingnose and on Inchgarvie

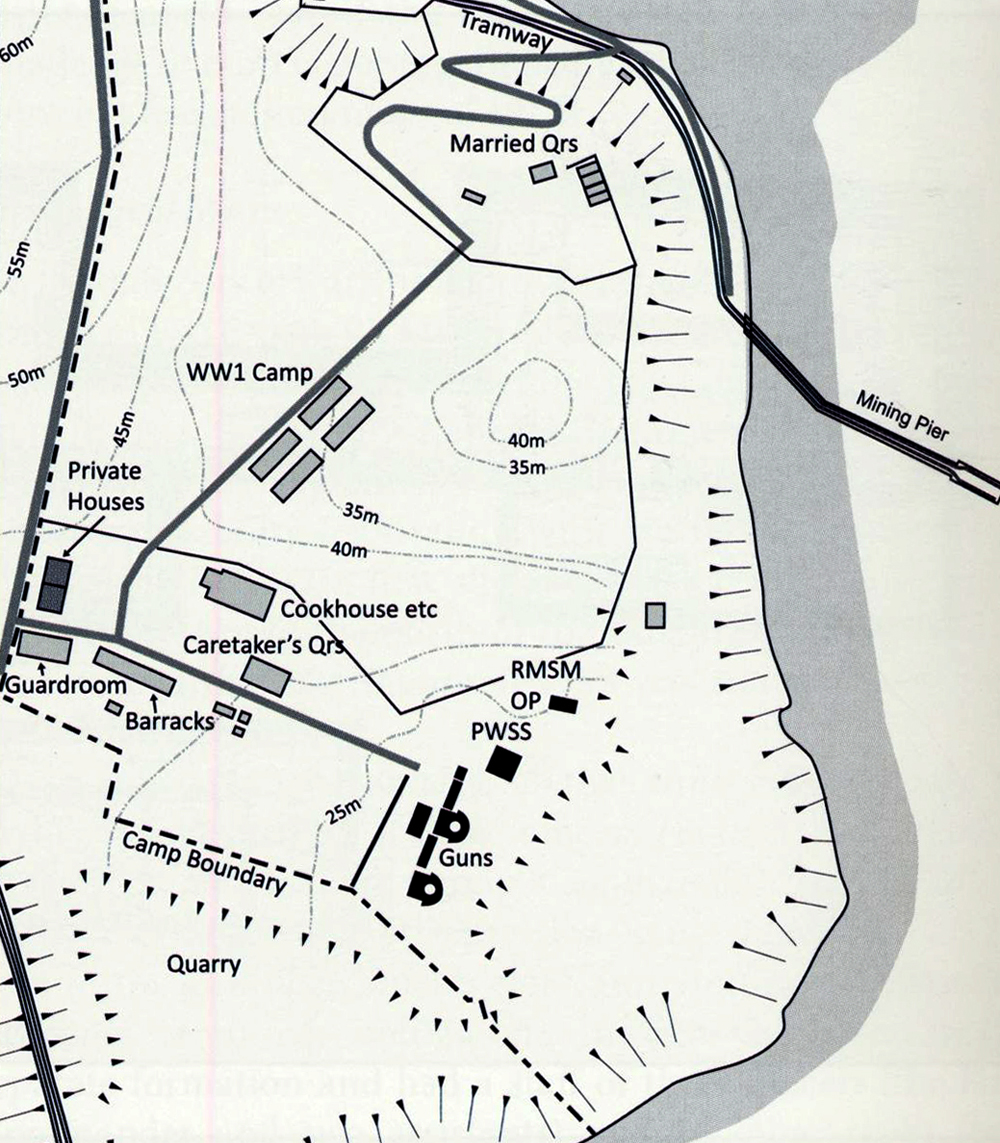

This map shows a WW1 camp of four huts at Carlingnose. These and a further twenty five huts were built to provide temporary accommodation during war-time.

Similar accommodation was also provided for the gunners on Inchgarvie.

The huts were sold in 1920.

1914 – Rosyth Dockyard progress

The outbreak of war forced a change of plan in the construction of Rosyth Dockyard. The work was on schedule but nothing was usable, so work was reorganized to bring as many facilities into use as soon as possible. The submarine basin was completed almost immediately providing a basin and jetties for small craft from September 25th 1914.

1915 – Hawkcraig experimental air station

A new experimental air station – HMS Tarlair opened at Hawkcraig in Aberdour in 1915. This used a seaplane to spot submarines and then to direct a radio-controlled unmanned motor boat filled with explosives to detonate above the submarine.

March 1916 – The completion of Rosyth Dockyard

By early 1916, the main basin was complete, the approach channel had been dredged and the emergency entrance and entrance lock were ready.

On the 27th March 1916 H.M.S. “Zealandia” passed through the emergency entrance and was subsequently docked in No. 1 dock.

In April 1916 H.M.S. “Dominion”, “Calliope”, “Constance”, “Tyne”, “Dreadnought” and “Invincible” entered the basin, and on the 27th April 1916 H.M.S. “New Zealand” was docked in No. 2 dock. The new establishment was thus, though far from complete, available from this time onwards for the use of the largest ships of H.M. Navy.

March 1916 – German Zeppelin Raids

The Germans were aware that the dockyard was nearing completion and tried to damage it. Three Zeppelins set off to raid Rosyth on the night of 5th / 6th March 1916, but were diverted by high winds

The Germans tried again on the night of 2nd / 3rd April 2016. Four airships set off to bomb the dockyard and the bridge. Two reached the Forth: L14 failed to find the intended targets and bombed Edinburgh and Leith; L22, having bombed empty fields near Berwick-upon Tweed, dropped its few remaining bombs on Edinburgh.

In response to this, the Royal Flying Corps formed 77 Squadron as a Scottish home defence unit, headquartered in Edinburgh. Detachments were formed at Turnhouse, and at Whiteburn (Grant’s House) and New Haggerston near Berwick-upon-Tweed.

RFC Aerodromes and Landing Grounds around the Forth in WWI

May 1916 – Battle of Jutland

In May 1916 Admiral Scheer tried again to lure the cruisers of the Grand Fleet into an engagement with the full force of the German High Seas Fleet at what became the Battle of Jutland on 31 May to 1 June 1916. Both sides claimed victory.

However although the British suffered higher losses, the Grand Fleet was able to resume action immediately, while the repairs to the High Seas Fleet put it out of commission for several months, and it remained effectively bottled up in port for the remainder of the war.

On the 1st June 2016 H.M.S. “Warspite” and on the following day H.M. ships “Princess Royal”, “Tiger”, and “Southampton” entered the main basin at Rosyth. All these ships had suffered considerable damage in the battle, and on the 5th June H.M.S. “Lion” arrived in a similar state. The necessary repairs and refit of these damaged ships were carried out in the docks and basin.

Nick Jellicoe, grandson of Admiral Jellicoe, has written a book about the battle and has created an excellent website about The Battle of Jutland which includes a video animation depicting the complex series of events.

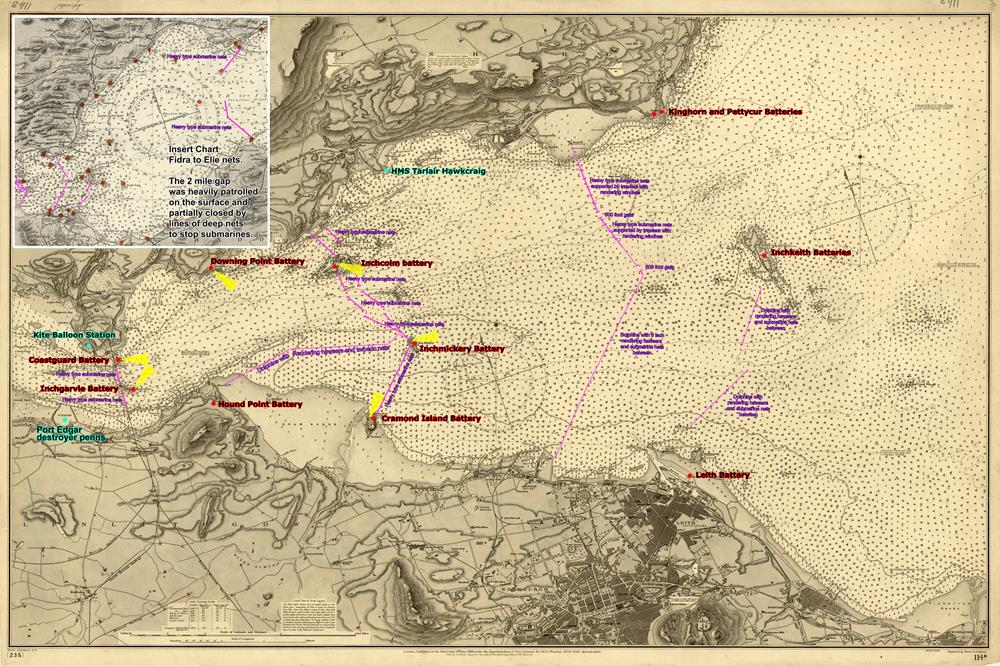

1916 – Expanding the Forth Defences and removal of Carlingnose guns

One of the aftermaths of the Battle of Jutland was the need to base the battleships of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet further south than Scapa Flow, so that they could engage the High Seas Fleet more rapidly. It was decided that the entire Grand Fleet should be based on the Forth. This necessitated a further improvement in defence with a new Outer Line, and a reduction in armament on the Inner Line.

The guns from Carlingnose Battery were removed and installed at the new battery at Pettycur on 5 and 12 November 1916.

1916 – Acquisition of Admiralty House

The official opening of Rosyth Dockyard and the intention to base the Grand Fleet in the Forth led to the acquisition on 13 July 1916 of St Margaret’s, including the furnishings, under provisions of the Defence of the Realm (Consolidation) Regulations 1914. It was renamed Admiralty House.

1917 – Ferrybarns Kite Balloon Station

In 1917 Ferrybarns Kite Balloon Station provided the Grand Fleet with long-range observation of enemy forces.

Overall defences of the Forth in 1918

Overall defences of the Forth in 1918

1917 Anti-aircraft guns in North Queensferry

The Zeppelin attacks of 1916 led to an increase in Anti-aircraft gun positions around the Forth.

In 1916, there were AA guns at eight sites around the Forth: Crombie, Hillock Point, Rosyth, lnverkeithing, lnchmickery, lnchkeith, Arthur’s Seat (east Edinburgh) and Corstorphine (south-west Edinburgh)

By 1917 there were twenty sites: Crombie, Culross, Hillock Point, Rosyth, East Camps (near Dunfermline), Mastertown (near Rosyth, South Fod (near Rosyth, lnchcolm, lnchkeith, Leith, Arthur’s Seat (east Edinburgh), Corstorphine (south-west Edinburgh), Borrowstown (Bo’ness), Easter Dalmeny (south-east of Forth Bridge), Mannerston, Echline (south of Port Edgar), Ferry Hill (North Queensferry), Polmont (south of Grangemouth), Grangemouth, East Fortune Aerodrome- Sherriff Hall and East Fortune Aerodrome- East Linton.

The site at North Queensferry was manned by the 17th AA Company.

Interior of Barracks 17 AA Coy., North Queensferry” – a detective story

1918 – The Forth becomes the base for the entire Fleet

Once the Outer Line of defences was complete, the Battle Fleet sailed into the Forth to join the Battlecruisers on 12 April 1918. The Battle Fleet included the 6th Battle Squadron – USS Florida, USS Wyoming, USS New York, USS Delaware and USS Texas under Admiral Rodman USN – the United States Battleship Division Nine which the U.S. Navy sent In December 1917 to replace the British ships lost at Jutland. USS Arkansas replaced USS Delaware in July 1918.

By the end of the year the Grand Fleet comprised 246 ships:

the Battle Fleet of 30 battleships, three armoured cruisers, 15 light cruisers, and six aircraft carriers; the Battle Cruiser Squadron, of 11 battle cruisers, 19 light cruisers;

Destroyer Command comprising two light cruisers and 160 destroyers, divided into seven flotillas.

All these ships could be accommodated behind the defences of the Forth. The Destroyers were based at Port Edgar.

The Forth defences by 1918 – new batteries at Pettycur and Leith created an Outer Line

The Forth defences by 1918 – new batteries at Pettycur and Leith created an Outer Line

The end of WWI

By late 1918, the leaders of the German Army had informed the Kaiser that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless, and that Germany should seek a negotiated peace with the Allies, on the basis of the “Fourteen Points” that had been publicized by President Wilson.

One of Wilson’s preconditions to beginning negotiation was the immediate cessation of Germany’s submarine warfare. Despite the objections of Admiral Scheer, the German Government made this concession on 20 October, and the U-boats at sea were recalled on 21 October.

In response on 22 October Scheer ordered Admiral Hipper to prepare for an attack on the British fleet utilizing the entire High Seas Fleet and the newly available U-boats. Hipper’s order was released on 24 October approved by Scheer on 27 October 1918 and the High Seas Fleet assembled off Wilhelmshaven on 29th October.

The evening of 29 October was marked by unrest and serious acts of indiscipline in the German Fleet, as the men became convinced their commanders were intent on sacrificing them, to sabotage the Armistice negotiations. Many stokers failed to return from shore leave, and mass insubordination occurred on most of the large ships in the fleet.

Admiral Hipper cancelled the operation on 30 October and ordered the fleet to disperse, in the hope of quelling the insurrection. However the mutiny gradually spread through the entire navy.

11th November 1918 – signing of the Armistice

After the naval mutiny, the peace negotiations resumed, and the Armistice was signed on 11th November 1918.

November 1918 – Surrender of the High Seas Fleet

At noon on November 13 1918, Admiral Beatty received a message that Admiral Meurer would act as negotiator for the German navy and would come to Rosyth in the light cruiser Koenigsberg. On the foggy evening of Friday 15th November 1918 Meurer arrived in the Forth and was escorted to the Queen Elizabeth, Beatty’s flagship. Three more meetings were held on Saturday 16th November 1918. Once agreement was reached, Meurer sailed back to Germany.

On Tuesday 19th November 1918 the first batch of twenty submarines arrived off Harwich, and were escorted by Admiral Tyrwhitt’s destroyers. They anchored off shore, were inspected and their crews transferred to a German cruiser for immediate repatriation. British crews then took the submarines into port.

On Thursday 21st November 1918 the High Seas Fleet was escorted into the Forth by the Grand Fleet. Beatty sent a signal to the German Admiral – “The German Flag is to be hauled down at 15:57 [sunset] today Thursday and is not to be hoisted again without permission”.

The German ships were inspected on 22nd November 2018 to verify that they had been completely disarmed, and arrangements were at once made for sending them on to Scapa Flow.

There they remained while efforts to reach a peace agreement were negotiated in Paris.

Here are more details of the Surrender

And here is a full account of the Surrender with supplementary material

June 2018 – Scuttling of the High Seas Fleet

In June 1919 Rear-Admiral von Reuter ordered his captains to scuttle the entire fleet to prevent the ships being seized by any other navy. 51 of the 74 ships sank; the remainder were beached or sank in shallow water. Eventually all but seven were raised and broken up for scrap.

June 1919 – Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. It came into effect on 10th January 1920.

1922 to 1971 – Shipbreaking at Inverkeithing

Thos. W. Ward Ltd of Sheffield was a steel, engineering and cement business which began life in 1878 as coal and coke merchants then expanded to recycling metal for Sheffield’s steel industry, engineering and the supply of machinery. In 1894 Ward’s moved into ship breaking at many different locations in the UK. They began work at Inverkeithing in 1922, on the site of the old brickworks.

1928 to 1937 Scuttled German ships broken at Rosyth

After WWI operations at Rosyth were wound down. Short-time working was introduced in 1921, and the dockyard closed in 1925.

In 1928 the SMS Moltke was raised from Scapa Flow and towed to Rosyth; the only dry dock in Scotland that could handle her.

Moltke was followed by Kaiser and Seydlitz in 1929, Hindenberg in 1930, Von der Tann in 1931, Prinzregent Luitpold in 1932, Bayern in 1934, König Albert in 1935, Kaiserin in 1936, Friedrich der Grosse in 1937, and Grosser Kürfurst in 1938.

Here are more details of Raising the scuttled German Fleet.

1939 – 1945 World War II

The threat of war with Germany led to the reopening of Rosyth Dockyard in 1938 as a Navy base.

World War II defences

By WWII the defensive lines had moved downstream, with the outer line from Crail to Dunbar.

The WWI middle line became the WWII inner line with no naval defences at Queensferry.

However, the biggest difference was the threat of air raids. In 1938 the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain placed Sir John Anderson in charge of Air Raid Precautions (A.R.P.) – gas masks, air-raid shelters and evacuation plans. These all had an impact on the civilian population and especially on the village school

North Queensferry School – pre WWII Air Raid Precautions

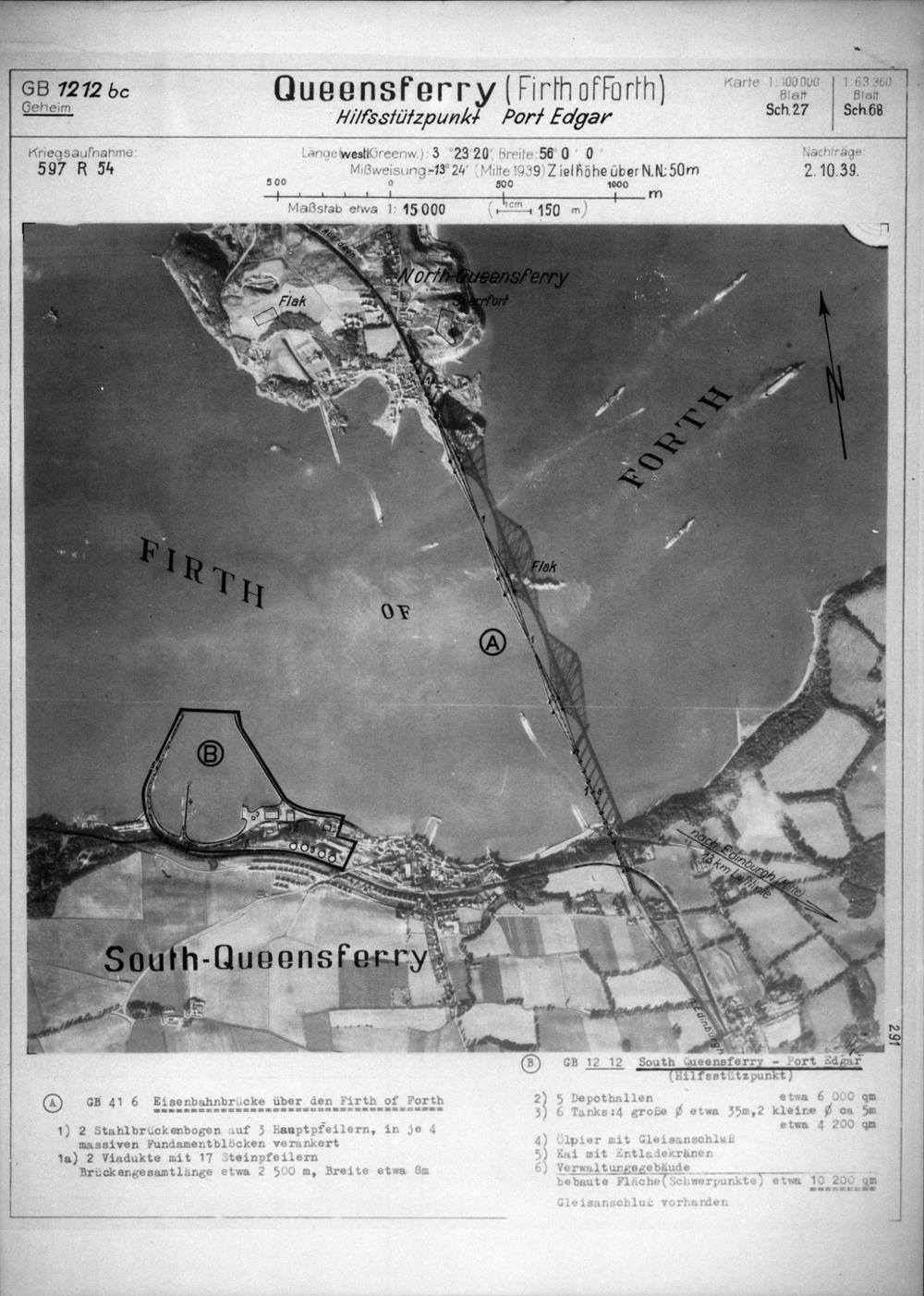

The Luftwaffe conducted many Reconnaisance Missions to photograph potential targets across Scotland.

Luftwaffe reconnaissance photograph with information added on 2nd October 1939.

Luftwaffe reconnaissance photograph with information added on 2nd October 1939.

The title of the photograph is: Queensferry (Firth of Forth), Hilfsstützpunkt [Auxiliary base] Port Edgar.

It is labelled: Nachträge 2.10 39. Nachträge translates as “supplements” so presumably the photograph was marked up on 2nd October 1939.

Here is a translation of the text beneath the photograph.

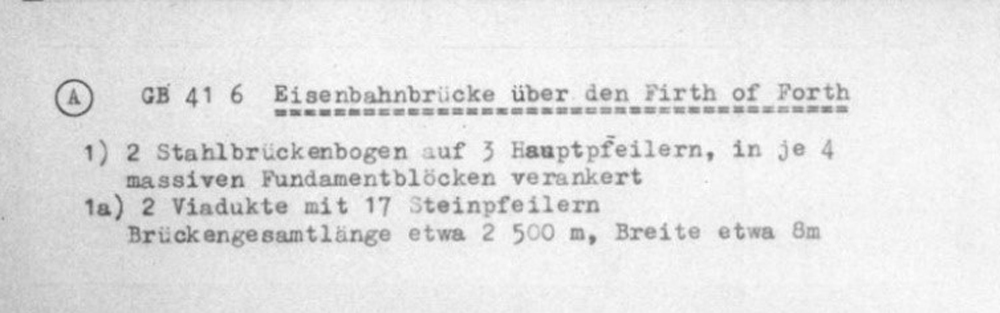

(A) GB 41 6 Railway Bridge over the Firth of Forth

1) 2 Steel bridge arch on 3 main pillars each anchored on 4 solid foundation blocks

1a) 2 Viaducts with 17 stone pillars

Bridges total length about 2,500, width about 8m

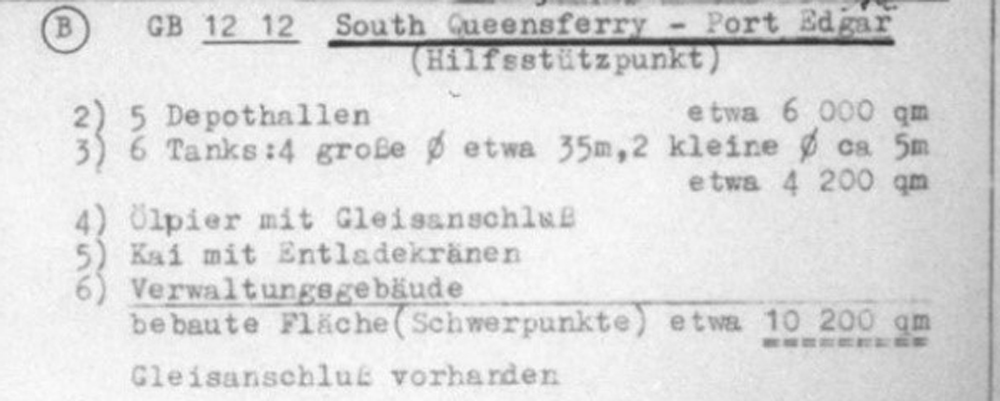

(B) GB 12 12 South Queensferry – Port Edgar

(Auxiliary Base)

2) 5 Depot halls about 6 000 sq m

3) 6 Tanks: 4 Large Dia about 35m, 2 small dia ca 5m about 4 200 sq m

4) Oil pier with track connection

5) Quay with unloading crane

6) Administrative office

———————————————————–

Built-up area (focal points) about 10,200 sq m

Track connection available

The gun-site in North Queensferry is labelled as Sperrfort, which translates as something like “defensive fort.” There are flak positions marked on Inchgarvie and on the site of the community centre in North Queensferry.

(In WWII, Germany’s main heavy anti-aircraft gun was the Flugabwehrkanone [aircraft defence cannon] 36 88mm multi-purpose gun, which was soon shortened to “flak”, which became the generic name for anti-aircraft fire.)

However these may be misinterpretations of the photographs because there is no mention of anti-aircraft guns at these sites engaging the enemy during accounts of the first air raid of the war two weeks later on 16th October 1939.

16 October 1939 – The First Air Raid of WWII

Following earlier reconnaissance missions, the Luftwaffe launched the First Air Raid of WWII against Royal Navy ships in the Firth of Forth on 16 October 1939.

That morning, two Heinkel 111 bombers probed the aerial defences and reported back on weather conditions and potential shipping targets in the Forth. In the afternoon twelve Junkers 88 bombers in four staggered groups of three, crossed the coast around Dunbar and headed towards the Forth Bridge. Each bomber had a crew of four. They dropped bombs on several ships, damaging the cruisers HMS Southampton and HMS Edinburgh which were berthed next to the Forth Bridge. A later wave caused severe damage to the destroyer HMS Mohawk which was off the coast at Elie, escorting a convoy from the Norway to Methil. The raiders met with anti-aircraft gunfire and were chased by Spitfires of 603 (City of Edinburgh) squadron from Turnhouse and 602 (City of Glasgow), squadron which was normally based at was based at Abbotsinch but had moved to on 13 October, to RAF Drem, in anticipation of German raiders from the east.

Two of the Junkers were shot down and ended in the Forth. One crashed off Prestonpans, three of the crew were rescued but the fourth had been killed and went down with the plane. The other ditched off Crail, two of the crew had been killed the other two were rescued but one died the following day. A third was damaged and made a forced landing in the Netherlands killing all four crew.

Sixteen Royal Navy sailors died and 44 were injured. Bombs landing near HMS Mohawk sprayed her with splinters killing 13 ratings and two officers. Commander Richard Frank Jolly was wounded in the stomach but refused to leave his post or to receive medical attention, with the words, “Leave me, go and look after the others.” He continued to direct the Mohawk for the 35 mile passage to Rosyth, which took eighty minutes. Although he was too weak for his orders to be heard they were repeated by his Navigating Officer who was also wounded. Five hours after he brought the ship into port he died aged 43. He was awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal posthumously. On 24 September 1940, this was exchanged by his family for the George Cross, upon the inauguration of the new medal.

October 1939 – Barrage balloons

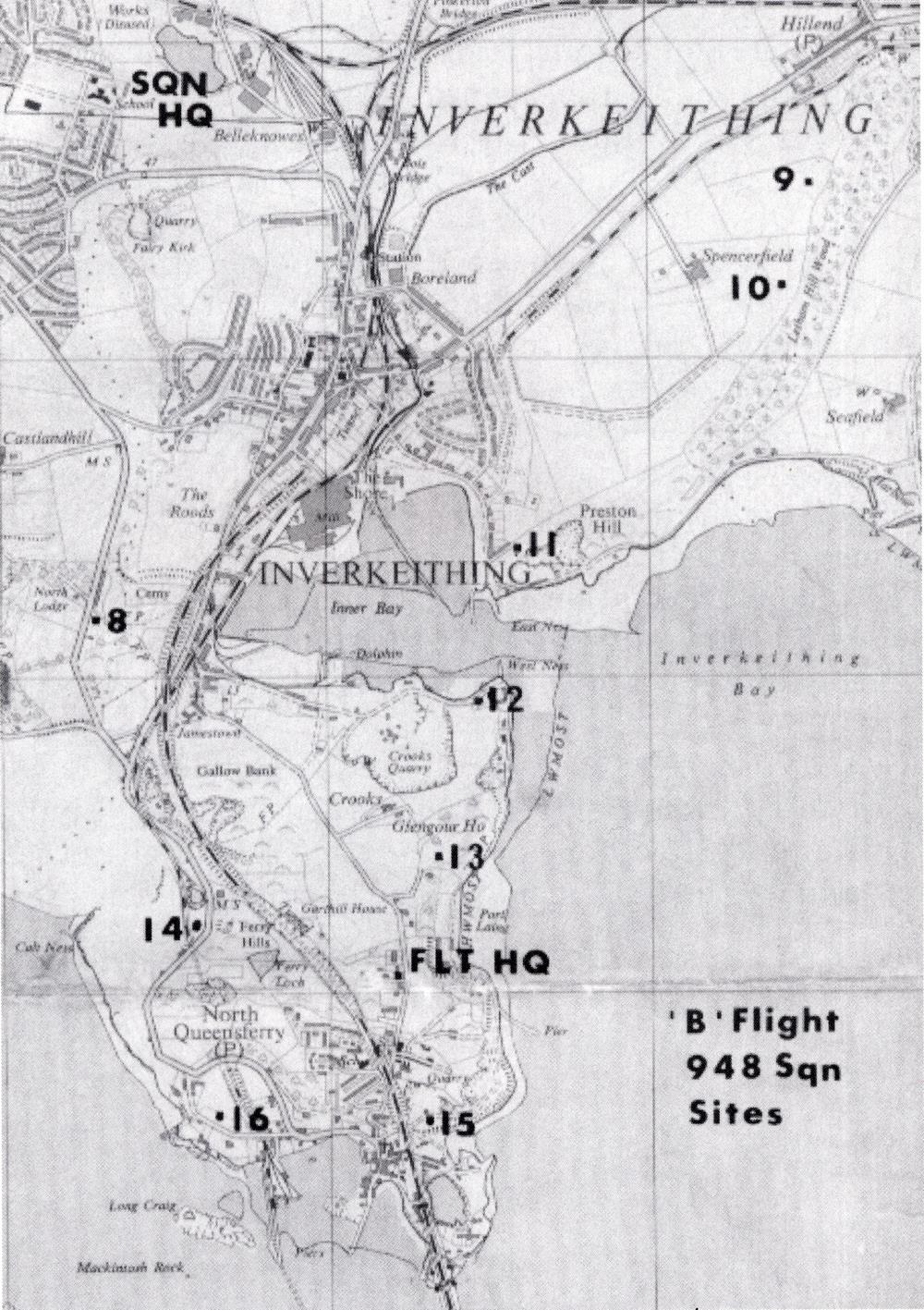

On 21st October 1939 a company of RAF auxiliary airmen from Middlesex who had been called up for service that August arrived by train at Inverkeithing. “B” Flight, 948 Squadron comprising a Flight Lieutenant, a Flying Officer and 114 other ranks had been allocated the area from North Queensferry to Belleknowes to set up nine anti-aircraft barrage balloon sites.

These gas-filled balloons were tethered with steel cables to create a defensive fence round potential air-raid targets.

One of the “other ranks” was Bob Cubin. In 1996, he published “No flight of fancy” about his war-time years in North Queensferry, where he came to live after the war.

Full details here – Barrage Balloon Sites round North Queensferry

1939 – Evacuation of schoolchildren

The other impact of the air raid was a request for evacuation, and 35 children travelled to Saline and Steelend on 30th October 1939. Even before war broke out, the school had been affected – it was occupied in August 1939 by a detachment of Cameron Highlanders. It had been occupied by the 6th (Perthshire) Battalion Royal Highlanders (Black Watch) during the summer holidays in 1914.

Full details here of North Queensferry School – the war years WWII Occupation and Evacuation and then North Queensferry School – the war years WWII returning to normality

c. 1980 – Thos Wards shipbreaking business closes at Inverkeithing

The Company was taken over by Forth Ports in 1986. They still owned the land and the berth but the facility is on long term lease to Robertson Metals, a local salvage company.

1996 – Admiralty House no longer used by the Admiralty

In 1996, the house was handed over to the Scottish Executive and then leased out to a private company, Universal Steels. It was acquired by Transport Scotland in the early 2000s as it is adjacent to the Queensferry Crossing.

Index to the sites

Here is an index to Twenty Military Sites around North Queensferry Peninsula

top of page