Naval Air Power in WWI

A Brief History of British Naval Aviation

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was constituted by Royal Warrant on 13 April 1912. It consisted of two wings: the Military Wing making up the Army element and the Naval Wing, under Commander C. R. Samson.

On 1 July 1914, the Naval Wing became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

By the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the RNAS had 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons and 727 personnel. The Navy maintained twelve airship stations around the coast of Britain from Longside, Aberdeenshire in the northeast to Anglesey in the west. The RFC had several hundred airfields around the country.

Before techniques were developed for taking off and landing on ships, the RNAS had to use seaplanes in order to operate at sea. Beginning with experiments on the old cruiser HMS Hermes, special seaplane tenders were developed to support these aircraft. It was from these ships that a raid on Zeppelin bases at Cuxhaven, Nordholz Airbase and Wilhelmshaven was launched on Christmas Day of 1914. This was the first attack by British ship-borne aircraft.

On 1 August 1915 the Royal Naval Air Service officially came under the control of the Royal Navy.

On 1 April 1918, the RNAS was merged with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) to form the Royal Air Force.

At the time of the merger, the Navy’s air service had 55,066 officers and men, 2,949 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 coastal stations.

The RNAS squadrons became the Fleet Air Arm of the new structure, individual squadrons receiving new squadron numbers by effectively adding 200 to the number so No. 1 Squadron RNAS (a famous fighter squadron) became No. 201 Squadron RAF.

The Royal Navy regained its own air service in 1937, when the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Air Force (covering carrier borne aircraft, but not the seaplanes and maritime reconnaissance aircraft of Coastal Command) was returned to Admiralty control and renamed the Naval Air Branch.

In 1952, the service returned to its pre-1937 name of the Fleet Air Arm.

Aviation Pioneers

On December 17th 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, sustained, powered heavier-than-air flight, on a beach four miles south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

That flight lasted 12 seconds, and covered 37 metres. The fourth flight later that day covered 260 metres in 59 seconds.

On October 16th 1908, Samuel Franklin Copy made the first sustained aeroplane flight in Britain, at Laffans Plain, Farnborough. He built his own plane in 1907 at the Army Balloon factory in Farnborough – “The British Army Aeroplane No 1” or “Cody 1.”

The flight was of 464 metres, and ended in a crash – a wingtip touched the ground as Cody attempted to turn and avoid a tree.

On July 25th 1909, Louis Bleriot made the first powered flight across the English Channel, from Calais to Dover.

The flight lasted 36 minutes and 30 seconds.

Although the range of a flight had now been extended, manoeuvring was still a major issue. Even turning an aeroplane was a very difficult exercise. Bleriot crash landed at Dover.

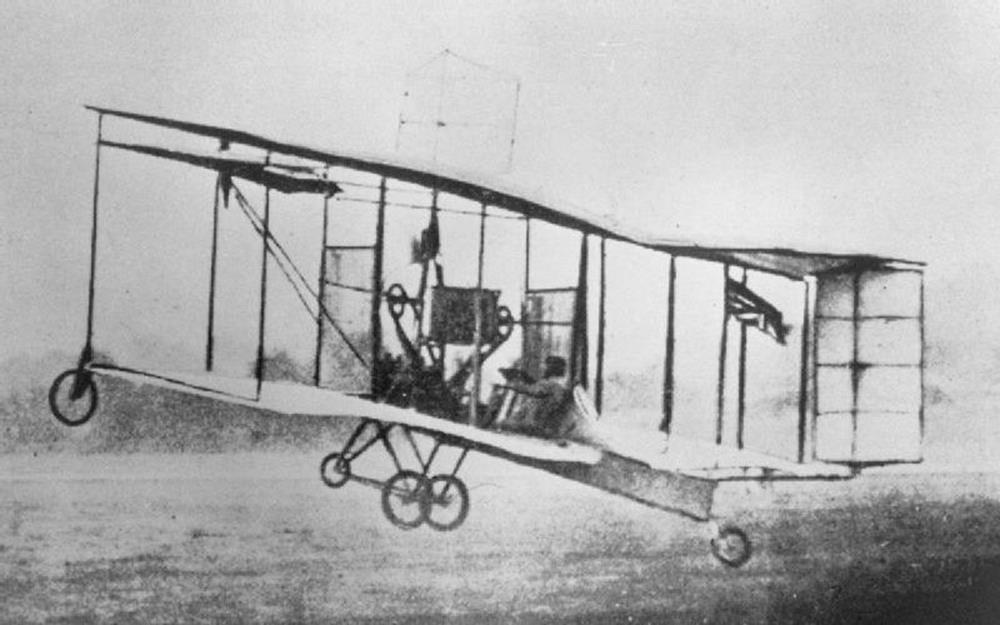

1911 – Scottish aviator W.H. Ewen flew across the Forth from Edinburgh, turned, flew back and landed safely!

Ewen’s flight over the Forth demonstrated that aircraft had become much more manoeuvrable, he was able to fly across the river turn, fly downstream, turn back and then circle to identify a suitable landing field.

The Birth of British Naval Aviation

In 1908, the British government recognised that the use of aircraft for military and naval purposes should be investigated.

On 21 June 1910, Lt. George Cyril Colmore became the first qualified pilot in the Royal Navy, after paying for training out of his own pocket.

In November 1910, the Royal Aero Club, offered the Royal Navy two aircraft with which to train its first pilots. The Club also offered its members as instructors and the use of its airfield at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey. The airfield became the Naval Flying School, Eastchurch.

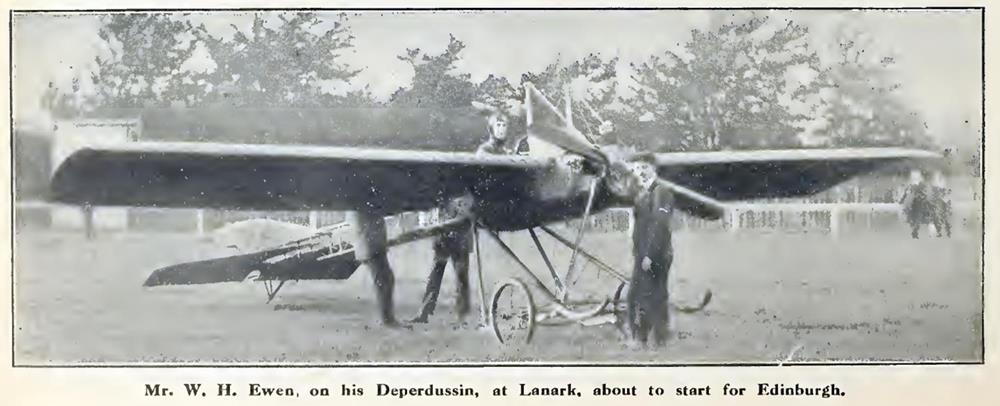

Two hundred applications were received, and four were accepted:

Lieutenant C. R. Samson,

Lieutenant A. M. Longmore,

Lieutenant A. Gregory and

Captain E. L. Gerrard, RMLI. [Royal Marine Light Infantry]

These four pilots were the genesis of what became the Royal Navy Air Service and later the Fleet Air Arm.

First British take off from a ship

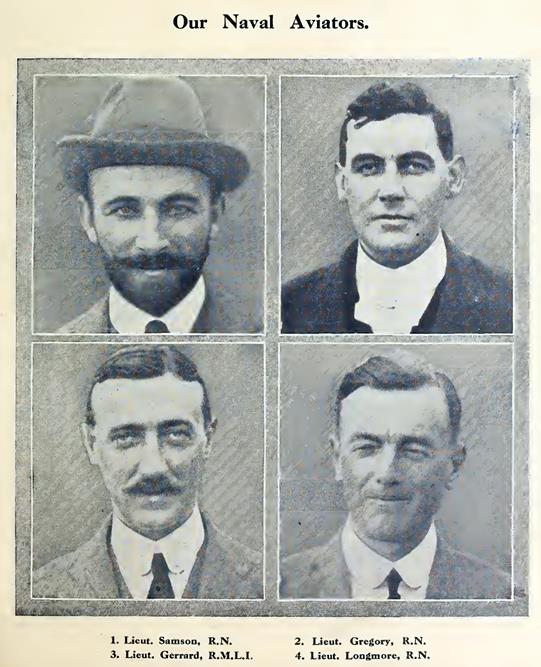

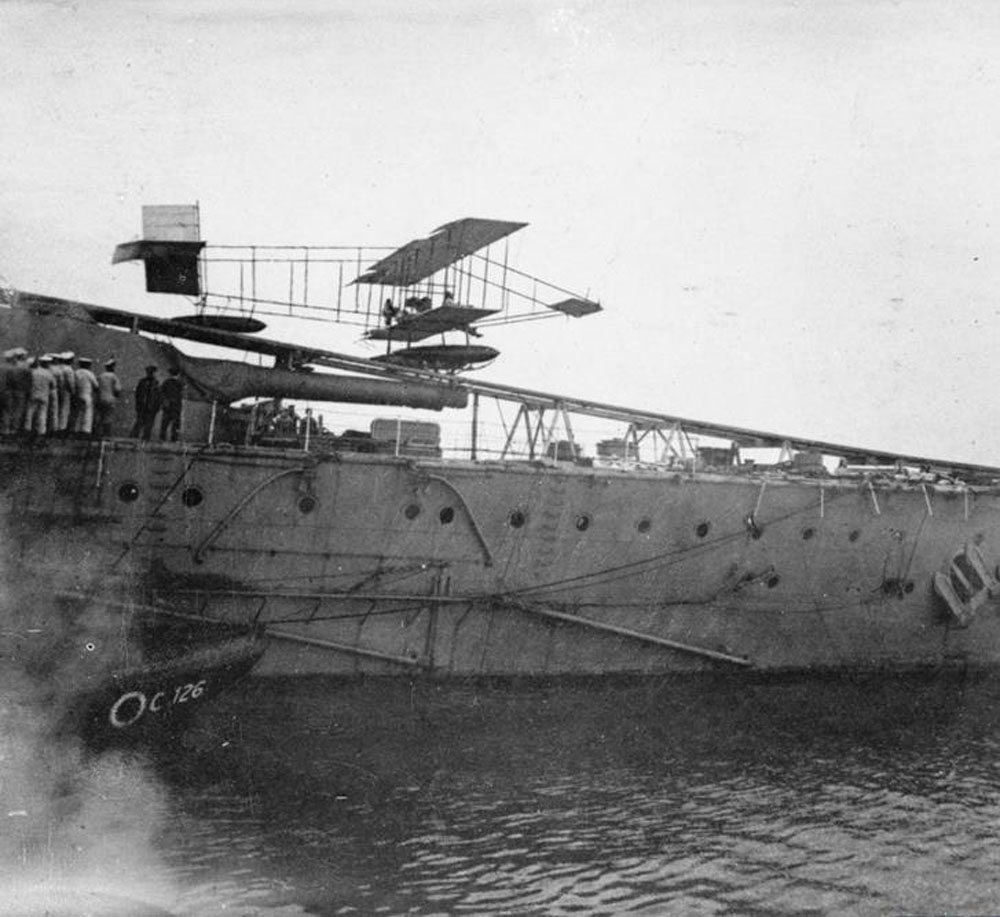

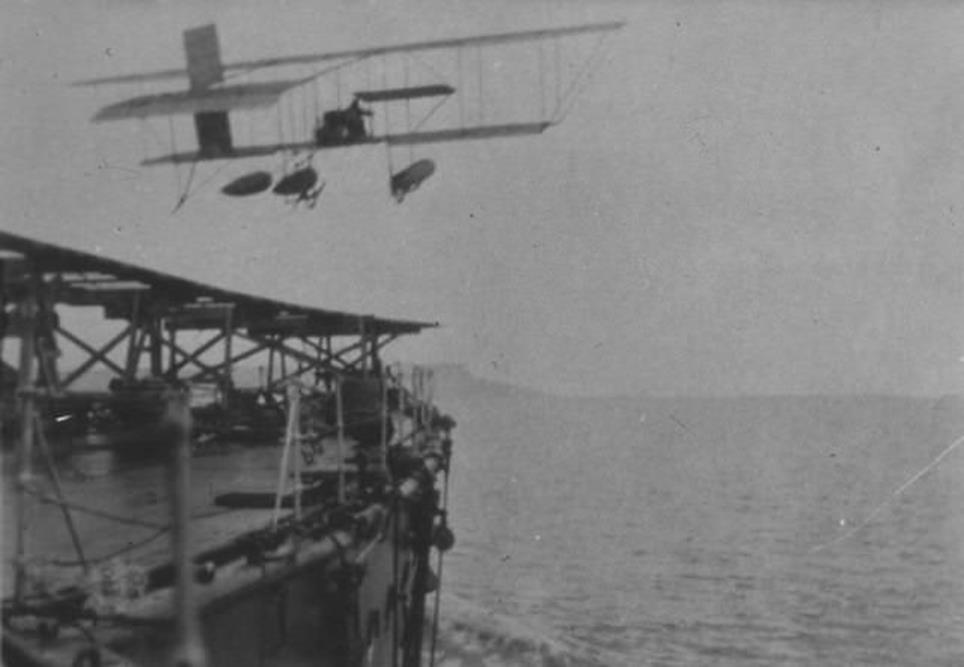

On 10th January 1912, Samson made the first British take-off of a plane from a ship. He flew a Short S.38 from a special ramp erected on the fore-deck of HMS Africa, moored off the Isle of Grain in the mouth of the Thames. It would be some time before a landing was attempted.

Later that year he repeated the feat, this time from a moving ship.

For the 1912 Royal Fleet Review at Weymouth, HMS Hibernia was fitted with a similar flying off platform. On the 2 May 1912 Lieutenant Samson, flying a Short-Sommer pusher biplane S.38, No. T.2, made the first ever take-off from a moving ship, The Hibernia steaming at 10.5 knots. Samson took off when the Hibernia was three miles off Portland Harbour. He rose to 45ft and then landed at the eastern end of Lodmoor.

Naval Aviation comes to North Queensferry

In 1912, the Royal Flying Corps was established, with a Military and a Naval Wing.

The Government announced the creation of a series of Air Stations, associated with the new east Coast Naval bases.

The first naval air station in Scotland was at Port Laing, just along from the old Submarine Mining Station.

First Flights from Port Laing

Scotsman – Thursday 3rd October 1912

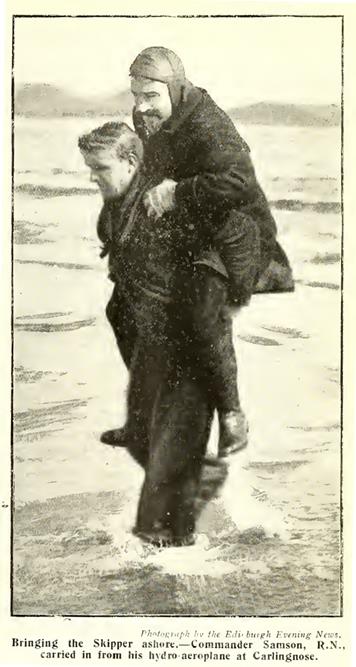

Yesterday forenoon the new hydroplane station established at Port Laing, near North Queensferry, was opened by two flights being carried out by Commander Samson and Captain Gordon. Three machines have been placed in the hangars, and would have operated previously, but the very stormy weather experienced at the beginning of the week precluded all possibility of any attempt at flying being made, more especially as the wind has been persistently from the east and north-east.

With the improvement which has set in in the weather during the night, it became known that flying would be engaged in yesterday morning and at a comparatively early hour people were seen concentrating on Port Laing form the surrounding district. When the hangar of No. 10 hydroplane was thrown open Commander Samson, having made a preliminary examination directed its removal to the sandy beach whence it was launched by a strong force of bluejackets. The carrying wheels however, lodged in the soft sand at high water mark, and the services of some fifty navvies on strike from Rosyth Naval Base were called to the aid of the launching party, and the machine was soon dragged again to solid ground.

Their mission was to spot submarines underwater, by observing the wake and eddies left by their passage.

The Sphere – April 1913, page 65

Some interesting experiments have been made in the course of the flying week at Rosyth to test the visibility of a submarine when viewed from above. The experiments were of a similar nature to those made by “The Sphere” in the English Channel last year. The recent Forth experiments showed that the water of the Forth is sometimes too muddy to enable the hydroplanes to see the submarine even when viewed directly from above. Yet the hydroplane could always “spot” its submerged enemy: the swirl of bubbles and foam which rode in the wake of the submarine was an infallible index to its position. The experiments confirmed the expected use of the hydroplane in this direction. The machine shown here is the 70 hp Short biplane converted into a hydro aeroplane by the addition of floats.

Looking after the pilot!

1913 – The Royal Flying Corps Military Air station at Montrose

While flying continued around the Forth during 1913, the newspapers became interested in activities further north, where the Military Wing of the RFC announced the establishment of their new Air Station in January 1913.

The Aeroplane. January 16, 1913 – The First Scottish Military Station.

One learns that the first of the Military aviation stations to be established at any considerable distance from headquarters is to be opened during the next few days at Montrose in Scotland. This will presumably be the chief military aviation station in Northern Britain, and situated as it is on a comparatively flat coast almost midway between Dundee and Aberdeen, it should be an excellent point for patrolling that portion of the east coast. The second squadron of the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps is to be stationed there, and it is very probable that a Naval station will be formed at the same place.

If the two stations are to be combined some interesting problems of Service precedence are likely to arise owing to the temporary rank of Army officers possibly making them academically senior to Naval officers who are not only their senior in rank but are actually their seniors in the Royal Flying Corps. However, it is hoped that no serious friction will arise between the Services.

The Aeroplane. February 13, 1913.

The Montrose station of the Royal Flying Corps has been established on 62 acres of land at Upper Dysart, 3½ miles south of the town and quite a mile from the coast. Its height above sea level is 300 ft. Though probably a permanent station, the land has only been taken on a five years’ lease.

Twelve canvas hangars are erected at present.

The Aeroplane. February 20, 1913.

On Thursday afternoon last [13th February 1913], five biplanes, three Maurice Farmans and two B.E.’s, all Renault-engined, set off from Farnborough on the first stage of the Montrose adventure. Captain Longcroft led the way at 2.30 p.m. on a B.E., after him at short intervals came Lieut. P. W. L. Herbert, Sherwood Foresters ; Capt. G. W. P. Dawes, Royal Berks ; Lieut. F. F. Waldron, 19th Hussars, and Capt. J. H. W. Becke, Sherwood Foresters, who is in charge of the flight. All are first-class pilots. Towcester was the first objective, the original route being altered on account of fog in the Thames valley.

The pilots were unaccompanied by passengers. A fleet of cars and motor lorries followed by road equipped with tools, spares, and stores. This was under the charge of Lieut. H. P. Atkinson, R.A. The landing places proposed are Towcester, Newark, York, Newcastle, and Edinburgh.

Three machines came down at Reading; the others returned to Farnborough, owing to fog.

This migration of a squadron to Scotland is part of the system according to which the R.F.C. is being developed.

From their preliminary training at the Central Flying School, at Upavon, it is intended that the military pilots shall pass to Farnborough, where their training is carried further, and the squadrons formed. As each squadron completes its training, it is to be despatched by air to its permanent post; Montrose being the first of these stations to be formed away from headquarters.

The flight of No. 2 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, was continued on February 17th, despite a very high wind. Captains Becke and Dawes and Lieutenant Herbert left Reading about 9 a.m., and Captain Longcroft and Lieutenant Waldron left Farnborough some two hours later. Captain Becke arrived at Towcester at 2 p.m., after one stop for petrol at Blakesley. One other pilot landed at Moreton-in-the-Marsh, one at Aylesbury, and Captain Longcroft and Lieutenant Waldron at Oxford.

The men and planes eventually arrived safely in Montrose.

1914 – The move from Port Laing to Dundee

The navy planes and pilots were based at Port Laing until January 1914, when they moved to Dundee. They were at Dundee until war broke out later that year.

The combination of winds around the cliffs, and the sticky sand were not ideal at Port Laing.

In addition, the artist Charles Martin Hardie was the owner of the land and he wanted to increase the rent substantially!

Finally, the MP for Dundee, was very keen on ships and planes – one Winston Spencer Churchill.

March 1914 – military manoeuvres at Leven

While work continued at the new base at Carolina Port in Dundee, the naval aviators took their planes to Leven, on the Forth to take part in some military manoeuvres in March and April 2014.

1st July 2014 – Formation of the Royal Naval Air Service

The big news of July 1914, apart from the belligerent rumblings from Europe, was the announcement of the creation of the Royal Naval Air Service as part of the Royal Navy, with the Royal Flying Corps focussing entirely on Army aviation.

This was to some extent a formal announcement of what had become the practical split between the Military and Naval Wings pf the RFC.

It would allow the Navy to concentrate on the development of seaplanes, and aircraft carriers both of which would have a role to play in the coming war.

28 July 1914 – World War I began

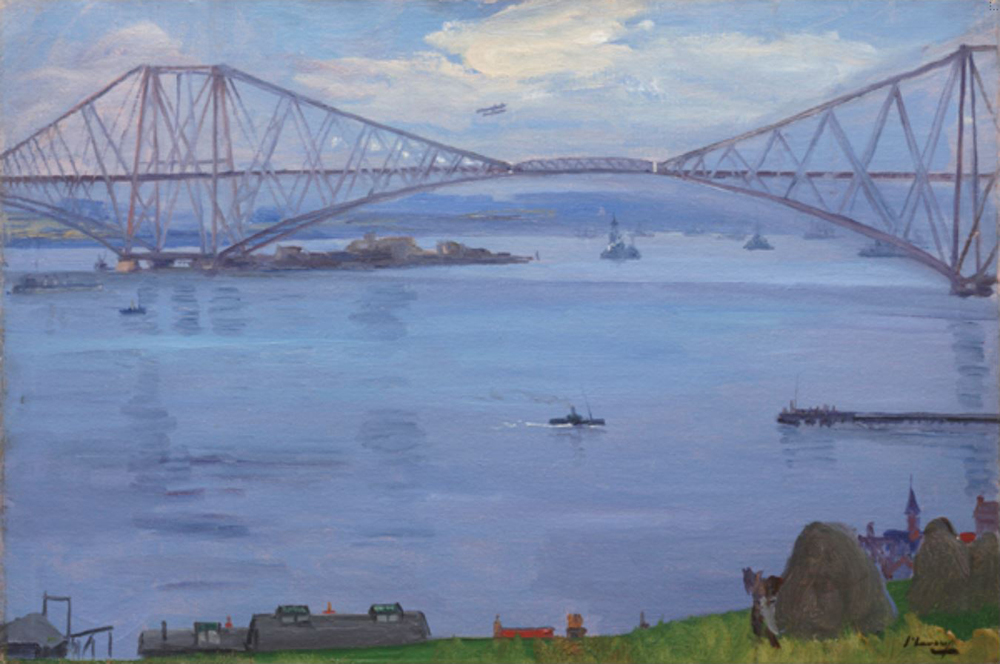

The Forth Bridge, – Sir John Lavery

This view was probably painted in September 1914, in the knowledge that war had recently been declared and that this tranquil scene would soon be transformed.

(Note the aeroplane just clearing the Forth Bridge, so perhaps it was painted, or sketched, at an earlier date.)

Military Aviation during WWI

At the outbreak of war, many of the men and machines from both Montrose and Dundee were mobilised and head south. The Royal Flying Corps supported the British Expeditionary forces in France, flying reconnaissance missions, while the Royal Navy Air Service provided air support for several detachments of marines in Belgium. Major Gordon, R.M.L.I., remained in Scotland, commanding the Northern Section of the R.N.A.S. Coast Defence System.

Reconnaissance aircraft.

At the start of the war, there was some debate over the usefulness of aircraft in warfare. However air reconnaissance played a critical role in the “war of movement” of 1914, especially in helping the Allies halt the German invasion of France. On 22 August 1914, British aircraft reported that a German was preparing to surround the British Expeditionary Force, contradicting all other intelligence. The British High Command took note of the report and withdrew toward Mons, saving the lives of 100,000 soldiers. Later, during the First Battle of the Marne, observation aircraft discovered weak points and exposed flanks in the German lines, allowing the allies to take advantage of them.

By the end of 1914 the line between the Germans and the Allies stretched from the North Sea to the Alps. The initial “war of movement” largely ceased, and the front became static, the focus for aeroplanes shifted to artillery spotting. By March 1915, a two-seater on “artillery observation” duties was typically equipped with a primitive radio transmitter transmitting using Morse code, but had no receiver. The artillery battery signalled to the aircraft by laying strips of white cloth on the ground in prearranged patterns.

Observation balloons

As the ground war settled into stalemate, manned observation balloons floating high above the trenches were used as stationary reconnaissance points on the front lines, reporting enemy troop positions and directing artillery fire. Balloons commonly had a crew of two equipped with parachutes: upon an enemy air attack on the flammable balloon, the crew would parachute to safety. Recognized for their value as observer platforms, observation balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by large concentrations of antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft.

Fighter aircraft – introduction and evolution

The success of reconnaissance and artillery spotting led to an arms race to develop single-seater fighter aircraft, with forward firing machine guns that could attack reconnaissance scouts. By late1915 the German Fokkers had achieved air superiority, rendering Allied access to the vital intelligence derived from continual aerial reconnaissance more dangerous to acquire.

Great Britain had “started late” in aircraft development and initially relied largely on the French aircraft industry, especially for aircraft engines. Fortunately, two new British fighters that were a match for the Fokker, the two-seat F.E.2b and the single-seat D.H.2, reached the front in September 1915, and February 1916 respectively. These and the new French Nieuport 11, proved more than a match for the Fokkers and allowed the Allies to re-establish air superiority in time for the Battle of the Somme, (July to November 1916.)

But reconnaissance flying, like all kinds, remained a hazardous business. In April 1917, the worst month for the entire war for the RFC, the average life expectancy of a British pilot on the Western Front was 69 flying hours.

The allied success in 1916 prompted the Germans to completely restructure their air force creating specialist fighter squadrons, strategic bombing squadrons, and ground-support squadrons (that attacked infantry in a land battle with machine guns and light bombs.

At this time, counter fire from the ground was far less effective than it became later, when the necessary techniques of deflection shooting had been mastered.

The new organization and the new Albatros D.III aeroplane swung air superiority back to Germany in first half of 1917 and the much larger RFC suffered significantly higher casualties than their opponents. While new Allied fighters such as the Sopwith Pup, Sopwith Triplane, and SPAD S.VII were coming into service, at this stage their numbers were small, and suffered from inferior firepower: all three were armed with just a single synchronised Vickers machine gun. Meanwhile, most RFC two-seater squadrons still flew the BE.2e, which was fundamentally unsuited to air-to-air combat.

This culminated in the rout of April 1917, known as “Bloody April” when the Royal Flying Corps suffered particularly severe losses.

During the last half of 1917, the British Sopwith Camel and S.E.5a and the French SPAD S.XIII, became available in numbers. On the other hand, the latest Albatros, the D.V, and the Fokker Dr.I proved to be disappointments. By the end of 2017 the air superiority pendulum had swung once more in the Allies’ favour.

The surrender of the Russians in March 1918, released German of troops from the Eastern Front and gave them a “last chance” of winning the war before the Americans could become involved. The resulting “Spring Offensive”, opened on 21 March 1918. The main attack fell on the British front and resulted in deeper penetration than had been achieved since 1914. Many British airfields had to be abandoned to the advancing Germans in a new war of movement. Losses of aircraft and their crew were very heavy on both sides – especially to light anti-aircraft fire.

In the midst of this campaign, the separate British RFC and RNAS air services were consolidated into the Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918, the first independent air arm not subordinate to its national army or navy.

By the end of April 1918, the great offensive had largely stalled. The promised new German fighters, notably the Fokker D.VII, had still not arrived, and the Allied blockade of Germany was causing an increasing shortage of lubricating oil and spare parts – these were often salvaged from captured allied aircraft.

The second half of 1918 saw the increasing involvement of the United States, with all-American squadrons growing in numbers and experience, and being supplied with improved aircraft the twin-gun SPAD XIII, Sopwith Camel and S.E. 5a. By the war’s end, the Americans came to hold their own in the air; although casualties were heavy, as indeed were those of the French and British, in the last desperate fighting of the war. By September 2018 casualties in the RFC had reached the highest level since “Bloody April” – and the Allies were maintaining air superiority by weight of numbers rather than technical superiority.

Bombers

Before WWI, Britain had been concerned about Germany’s lead in airship development. (Britain’s first rigid airship – the Mayfly – broke in two in 1911 when it was mishandled on the ground and the development programme was more or less abandoned.) Concerns were raised that Zeppelins could be used as long-range bombers.

These concerns proved to be well-founded. In the opening weeks of the war Zeppelins bombed Liege, Antwerp and Warsaw, and other cities including Paris and Bucharest were targeted. And in January 1915 the Germans began a bombing campaign against Britain that was to last until 1918.

Gradually British air defences improved. In 1917 and 1918 there were only eleven Zeppelin raids against England, and the final raid occurred on 5 August 1918. By the end of the war, 54 airship raids had been undertaken, in which 557 people were killed and 1,358 injured.

By 1917, both Britain and Germany had developed similar types of bomber aeroplanes.

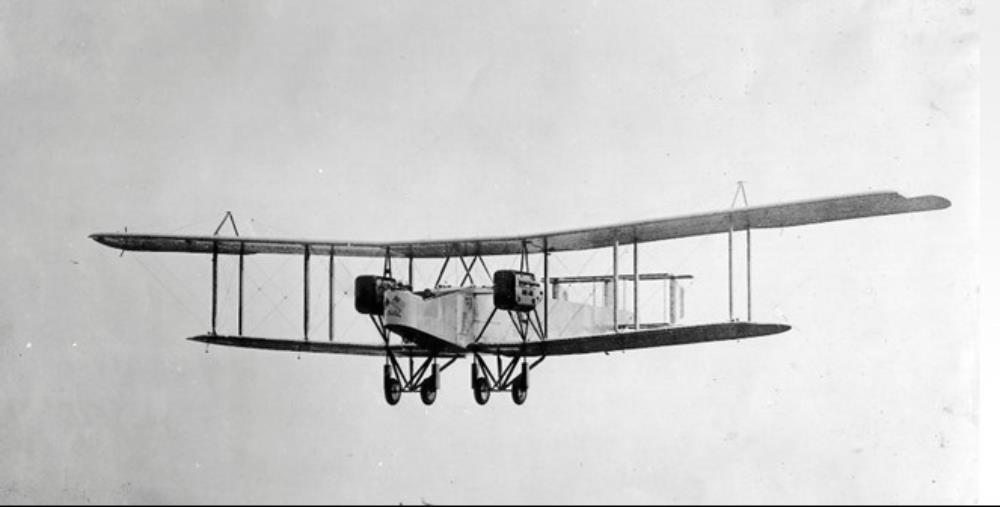

British Handley-Page 0/400 bomber

British Handley-Page 0/400 bomber

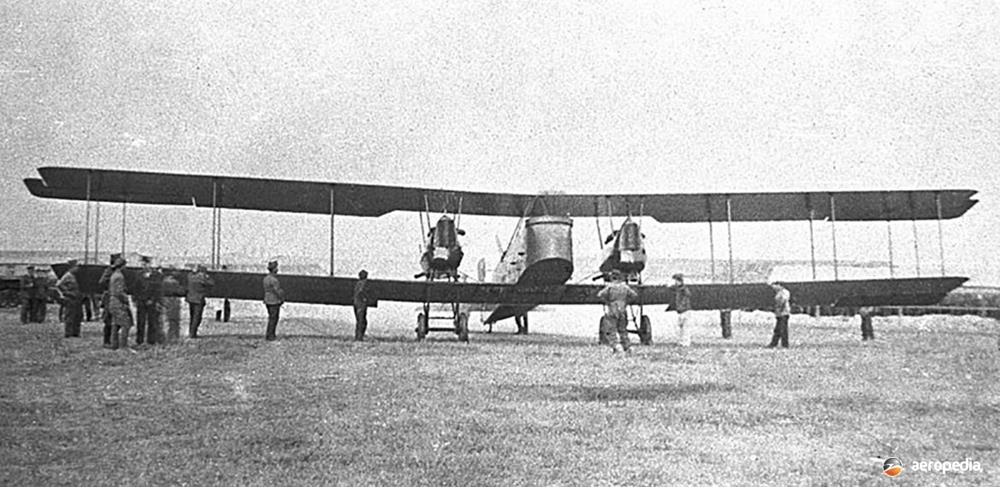

German Gotha G.V bomber

German Gotha G.V bomber

From September 1917 to May 1918, the Zeppelin raids were complemented by the Gotha G bombers and five Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI “giant” four engine bombers from late September 1917 through to mid-May 1918. Twenty-eight Gotha twin-engine bombers were lost on the raids over England, with no losses for the Zeppelin-Staaken giants.

Royal Navy Air Service in WWI

The RNAS pilots and aircraft were sent to Belgium and France to provide air support for regiments of marines, who conducted armoured car raids which severely disrupted German reconnaissance activities. Charles Samson’s squadron was heavily involved in this activity and also bombed the Zeppelin sheds at Düsseldorf and Cologne. By the end of 1914, when mobile warfare on the Western Front ended and trench warfare took its place, his squadron had been awarded four Distinguished Service Orders, among them his own, and he was given a special promotion and the rank of commander. He spent the next few months bombing gun positions, submarine depots, and seaplane sheds on the Belgian coast.

On November 21st, 1914, three RNAS aircraft flew from France and attacked the Zeppelin airship sheds and factory at Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance.

Seaplane Carriers

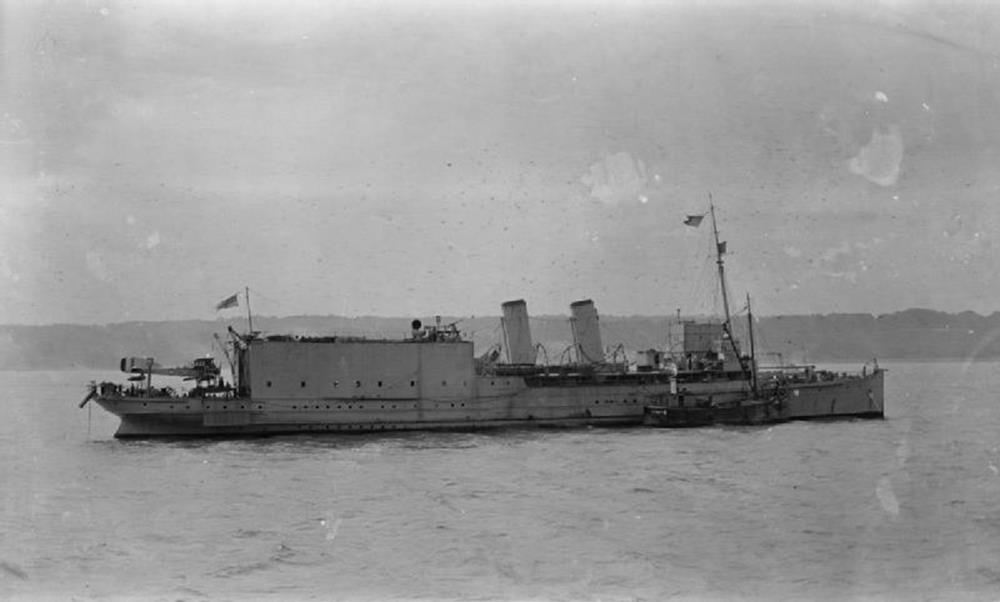

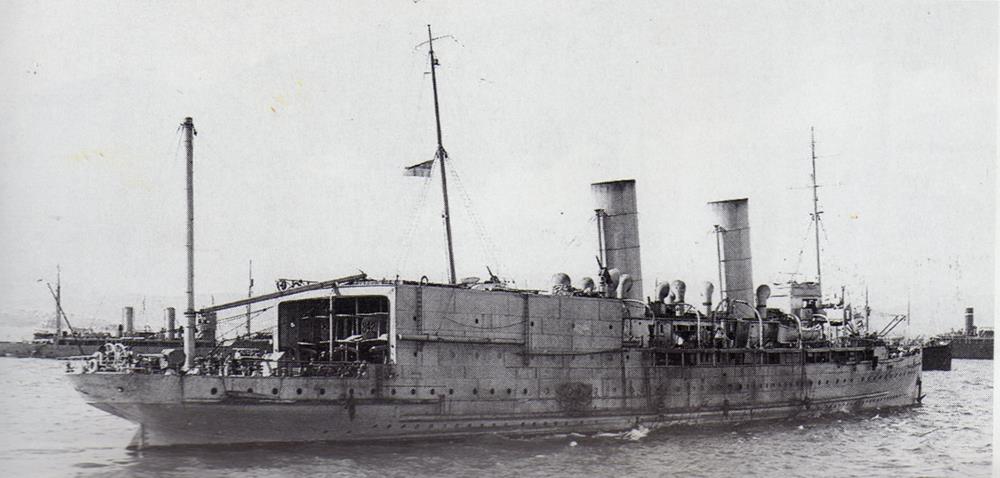

Samson’s success in flying off a moving ship in 1912, prompted the Royal Navy to develop aircraft carriers, of which the first was HMS Ark Royal, launched on 5th September 1914. Originally laid down as a merchant ship, she was converted on the building stocks to be a hybrid airplane/seaplane carrier with a launch platform.

HMS Ark Royal

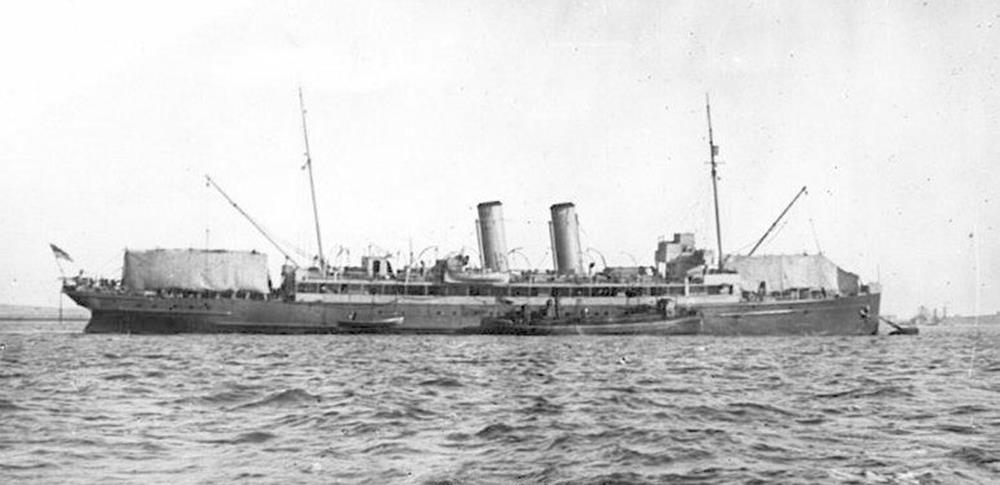

Another flyer from Carlingnose – Francis Hewlett – was involved in The Cuxhaven Raid on Christmas Day, 1914. Three cross-channel steamers converted into seaplane carriers, HMS Engadine, Riviera and Empress carried a total of twelve seaplanes from Harwich to the Heligoland Bight.

HMS Engadine

HMS Riviera

HMS Empress

In freezing conditions the planes were lowered onto the water.

A Short S64 “folder”

Two were unable to start, but seven all carrying three 20 lb (9.1kg) bombs) took off.

Fog, low cloud and anti-aircraft fire prevented the raid from being a complete success, although several sites were attacked including the Zeppelin sheds, aircraft hangers and several warships. According to a telegram dated 7 January 1915, held in the Churchill Archives Centre, an intercepted message from Hartvig, Kjobenhaven to the Daily Mail, reported that the raid had forced the German Admiralty to remove the greater part of the High Seas Fleet from Cuxhaven to various places on the Kiel Canal.

The crews of all seven aircraft survived the raid, having been airborne for over three hours.[6] Three, regained their tenders and were recovered; three others landed off the East Friesian island of Norderney and their crews were taken on board the submarine E11. The seventh aircraft, piloted by Flt. Lt. Francis E.T. Hewlett, ditched in the sea. Hewlett was picked up by a Dutch trawler and returned to the port of Ijmuiden in the Netherlands, from where he made his way back to Britain.

[Hewlett gained his pilot’s certificate in November 1911 having been taught to fly by his mother, Hilda Beatrice Hewlett (1864 – 1943) who was the first English aviatrix to earn a pilot’s license. A successful early aviation entrepreneur, she created and ran the first flying school in England, and also created and managed a successful aircraft manufacturing business which produced more than 800 aeroplanes and employed up to 700 people.

Hewlett earned a Distinguished Service Order in 1915 and rose to the rank of Group Captain RAF, and Air Commodore RNZAF.]

After the raid German seaplanes and airships set out to discover the position of the attacking force, and attacked it with bombs. No damage was done to the ship, seaplanes or airship. Further attacks on the retiring force were attempted by German submarines but were unsuccessful and the British force returned to home waters without loss or damage.

The raid demonstrated the feasibility of attack by ship-borne aircraft and showed the strategic importance of this new weapon.

The RNAS in the Dardanelles.

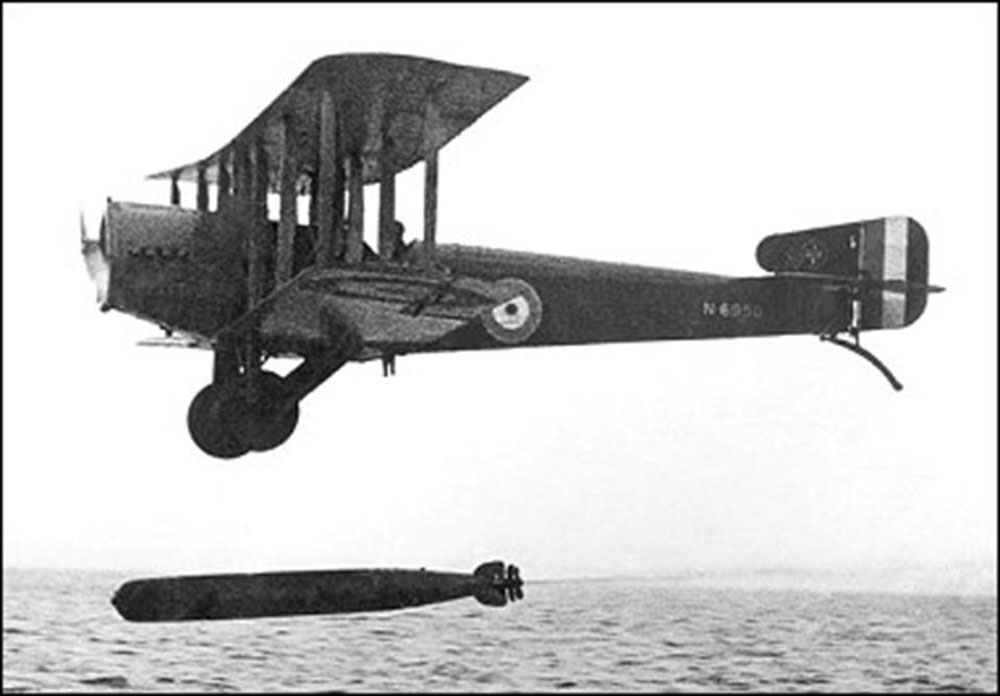

In March 1915 Samson was sent to the Dardanelles with No 3 Squadron and, together with seaplanes from HMS Ark Royal, initially provided the only Allied air cover. His squadron pioneered the use of radio in directing the fire of battleships and photo-reconnaissance. Samson flew many missions himself and became well known for waving cheerily to the Allied troops in the trenches below.

On 14 May 1916, Samson was given command of HMS Ben-my-Chree, a former Isle of Man passenger steamer which had been converted into a seaplane carrier.

HMS Ben-my-Chree

In almost continuous action through the rest of 1916, Samson received a signal from the Admiralty asking why Ben-my-Chree had used so much ammunition; he replied “that there was unfortunately a war on”. The Ben-My-Chree was eventually sunk on 11 January 1917 by Turkish gunfire.

From November 1917 until the end of the War, Samson was in command of an aircraft group at Great Yarmouth responsible for anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin operations over the North Sea

In 1919 he gave up his naval commission and received instead a permanent commission in the RAF with the rank of group captain. He went on to become Chief Staff Officer of the RAF’s Middle East Command. Retiring on account of ill health in 1929, he died in 1931.

Aircraft carriers

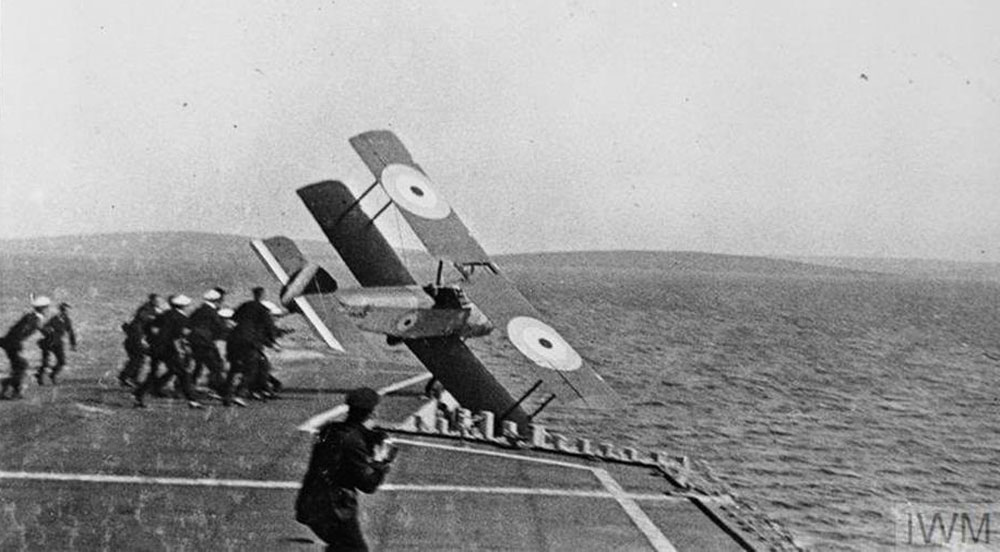

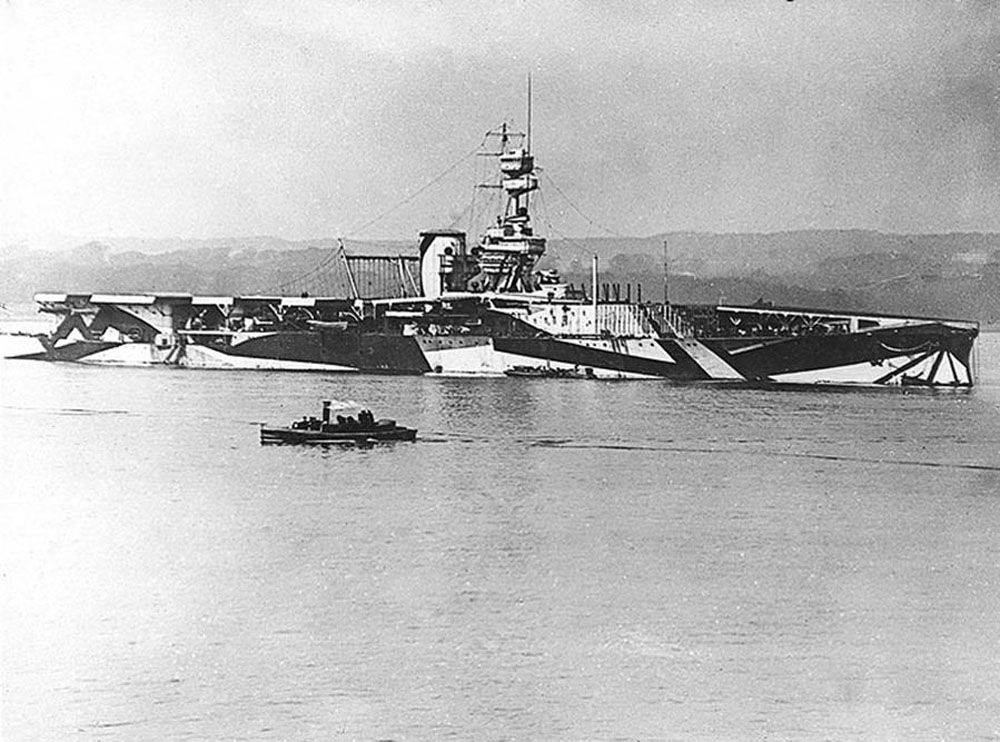

As well as sea-plane tenders, the Navy also worked on the development of aircraft carriers, the first was HMS Furious.

HMS Furious in 1917

Originally laid down in 1915 as a large light cruiser mounting two 18 inch (457mm) guns, the largest on any Royal Navy warship. In February 1917 her forward gun was replaced with a flying off deck. In a remarkable event on 2 August 1917 Squadron Commander E.H. Dunning landed his Sopwith Pup on Furious’ flying off deck, the first aircraft to land on a ship.

A few days later Dunning tried again but was killed when his aircraft went over the side.

As a result of Dunning’s accident a landing-on deck was built on the stern in late 1917.

HMS Furious in 1918

Furious launched the Tondern raid in July 1918 when seven Sopwith Camel aircraft attacked Zeppelin sheds destroying two airships, the first attack in history made by aircraft flying from a carrier flight deck.

The British conducted no other carrier raids during the war but other raids were being planned.

From 1917 onwards a raid on the German High Seas Fleet was mooted using the new torpedo-carrying Sopwith Cuckoo, but the Cuckoo was not available in sufficient numbers until early 1919 after the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet in November 1918.

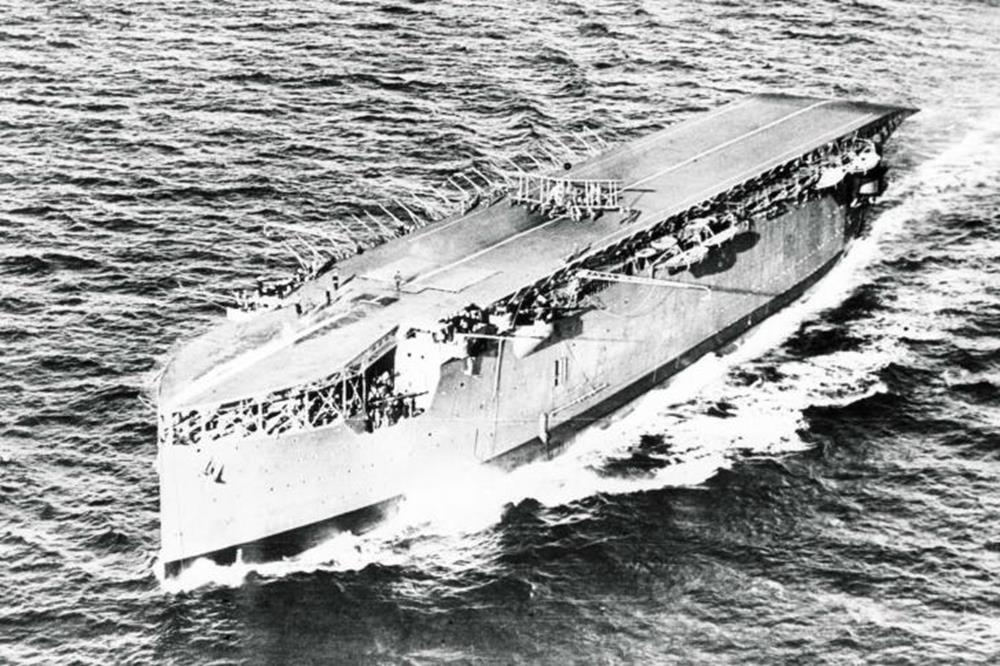

The limitations of HMS Furious led to the introduction in 1918 of the first flat-top carrier with a full-length flight deck – HMS Argus.

HMS Argus

In 1916 as the limitations of existing carriers became apparent, the Admiralty sought large, fast hulls suitable for conversion into an aircraft carrier. Construction of the Italian ocean liners Conte Rosso and Giulio Cesare had been suspended by William Beardmore and Company at the outbreak of the war, and both met the Admiralty’s criteria. Conte Rosso was purchased by the Admiralty on 20 September 1916, and Beardmore began work on converting the ship.

The design went through various iterations aimed at deleting turbulence above the flight deck. These led to the deletion of funnels (exhaust gases were ducted aft and exhausted underneath the aft end of the fully-flush flight deck.

She was introduced too late to see service in WWI but was used to test arrestor gear and then as a training ship, and saw active service in WWII.

top of page