Progression of Naval Warfare

Naval tradition

As an island nation, Britain has always had a powerful navy for defense, and later as the means to build an empire. By the start of the 19th century, the Royal Navy was the largest in the world.

“Hearts of Oak” wooden sailing ships, cannon, and perhaps a degree of complacency after their victory at Trafalgar in 1805 over the combined fleets of France and Spain.

The Industrial Revolution

In 1859 that complacency was shaken when France launched La Gloire – an iron-clad ship with sails and steam. Britain responded by building HMS Warrior in 1860 – the industrial revolution had taken to the waves, triggering an arms race.

Mines and torpedoes

Naval battles during the American Civil War 1861 to 1865 proved the worth of ironclads over wooden hulls, and also the potential of mines, torpedoes and submarines. Navies around the world took note.

In Britain, the Government conducted experiments into the potential of electrically-controlled mines to defend harbours, and by 1870 the Submarine Mining Division of the Royal Engineers was created. Their mission was to be able to deploy defensive minefields in time of war across the mouths of the main Royal Navy harbours of The Medway, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Pembroke and Cork.

In 1871, the Royal Navy bought manufacturing rights, and started producing the Whitehead torpedo at the Royal Laboratories at Woolwich, England.

Torpedo boats

Another spin-off from the American Civil War was the torpedo boat. Britain’s first purpose-built torpedo boat was HMS Lightning in 1876. A small nimble torpedo boat armed with the Whitehead torpedo, could attack a large battle-ship. It was fast and small, so presented a very difficult target for the big guns on a battleship, which conversely presented a large target for the torpedo.

Destroyers

To counter the threat from torpedo boats, navies around the world added smaller, quicker-firing guns to existing ships. They then developed custom gunboats designed with the explicit purpose of hunting and destroying torpedo boats. By the 1890s these had evolved into the much faster Torpedo Boat Destroyers, eventually known simply as destroyers.

The first Royal Navy destroyers were HMS Daring and HMS Decoy. They were armed with one 12-pounder gun and three 6-pounder guns, one fixed 18-in torpedo tube in the bow and two more torpedo tubes on a revolving mount at the stern. They had a top speed of 27 knots, giving the range and speed to travel effectively with a battle fleet and provide a protective screen.

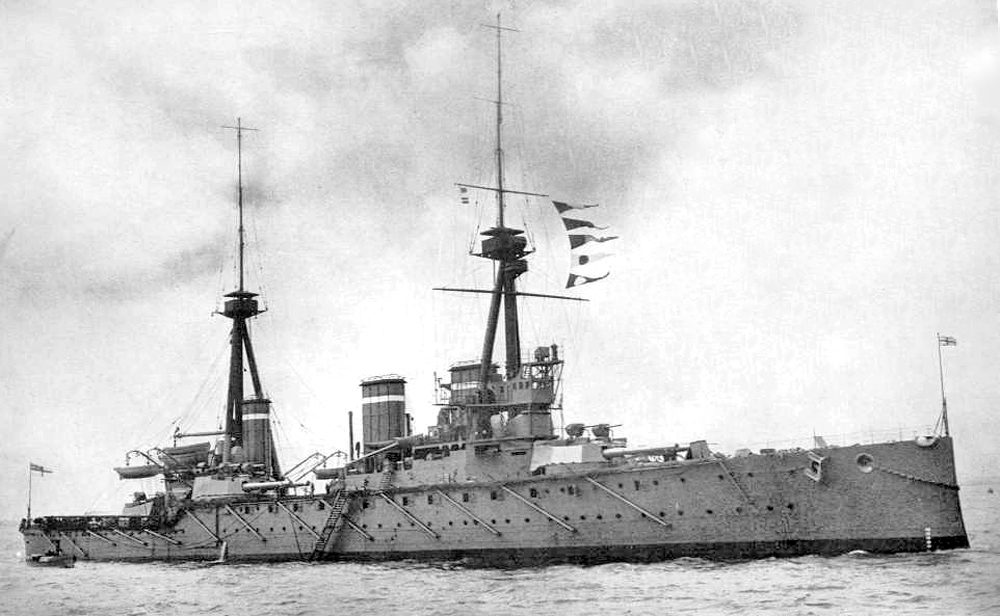

Pre-dreadnought battle ships

By the 1890s new all-steel battleships protected by hardened steel armour, with heavy guns in barbettes (open gun-houses) were introduced. These “pre-dreadnought” battleships were powered by coal-fuelled triple-expansion steam engines. The ironclads were now obsolete.

H.M.S. Hood – a typical pre-dreadnought battleship.

Cruisers

About the same time the armoured cruiser was introduced. It was designed to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast enough to outrun any battleship it encountered. It used the same guns as a battleship, but had lighter armour. This made it fast and agile so it could escape any encounter with a battleship. H.M.S. Cressy was built in 1898.

Submarines

In 1902 the first British submarine was launched, HMS Holland, using a design purchased from the Holland Torpedo Boat Company of the USA, but with an untested improved version of the original Holland design using a new 180 hp petrol engine. She was armed with the Whitehead torpedo.

HMS Holland

The Admiralty viewed submarine warfare, in the words of Rear Admiral Wilson, as ‘underhand, unfair, and damned un-English’. But the submarine gained a champion in Admiral ‘Jacky’ Fisher. Having watched the five Hollands ‘sink’ four warships in an exercise to defend Portsmouth Harbour, Fisher realised that naval warfare had changed.

1904 – Jackie Fisher became First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty. Having previously introduced the Torpedo Boat Destroyer to the Royal Navy, he now overhauled the entire fleet, and controversially diverted 5% of the Navy’s shipbuilding budget to the construction of submarines.

The submarine continued to develop from the Hollands through A to D classes. The D-class, with its decking and deck gun, represented a major change from the porpoise shape of earlier submarines, and introduced the form that would become familiar through two world wars.

At the start of World War One, the Royal Navy had the world’s largest submarine service by a considerable margin, with 74 boats of the B, C and D classes, of which 15 were oceangoing, with the rest capable of coastal patrols. The D-class, built 1907-1910, were propelled by diesel motors on the surface to avoid the problems with petrol engines experienced with the A class. These boats were designed for foreign service with an endurance of 2500 nautical miles at 10 knots on the surface and much improved living conditions for a larger crew. They were the first submarines to be equipped with deck guns forward of the conning tower. Armament included three 18 inch torpedo tubes They were so innovative that the prototype D1 was built in a securely guarded building shed.

The Germans were slower to recognise the importance of the submarine. A cancelled order by the Imperial Russian Navy from the Kiel shipyard in 1904 was modified and improved, then commissioned into the Imperial German Navy in 1906 as its first U-boat, U-1.

It had a double hull, was powered by a kerosene engine and armed with a single torpedo tube. The fifty percent larger U-2 launched in 1908 had two torpedo tubes. A diesel engine was not installed in a German navy boat until the U-19 class of 1912–13 which had the range (5,000 miles) and speed (eight knots) to operate effectively around the entire British coast. At the start of World War I, Germany had about 30 submarines in service with 18 more under construction.

Dreadnoughts

Fisher also overhauled the surface fleet and introduced the battleship HMS Dreadnought.

HMS Dreadnought

She was completed in a year and a day, and her combination of speed, guns and armour made all previous battleships obsolete.

Navies around the world all wanted dreadnoughts – the US, Japan, Italy Turkey, Brazil, Chile, Russia and of course Germany, who realized that if a dreadnought could be built in a year, they had a chance to reach 60% of the size of the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy pressed on with maintaining a 2:1 advantage over any other navy – we had coal, steel and money from the empire.

Battle Cruisers

Fisher also revolutionised the design of battle cruisers, with the Invincible class introduced in 1906. The were 40 feet (12.2 m) longer than a Dreadnought to accommodate additional boilers and more powerful turbines to propel them at 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph). The The new ships could maintain this speed for days. They were armed with with eight 12-inch guns, compared to ten on Dreadnought, and carried 6–7 inches (152–178 mm) of armour (Dreadnought’s armour, by comparison, was 11–12 inches (279–305 mm) at its thickest.)

The Invincibles were intended to give the Royal Navy an edge in defending the empire against the then-expected enemies such as France and Russia, who both had large fleets of armoured cruisers.

Naval Aviation

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was constituted by Royal Warrant on 13 April 1912. It consisted of two wings: the Military Wing making up the Army element and Naval Wing, under Commander C. R. Samson.

On 1 July 1914, the Naval Wing became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

In August 1914, the RNAS had 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons and 727 personnel. The Navy maintained twelve airship stations around the coast of Britain from Longside, Aberdeenshire in the northeast to Anglesey in the west. The RFC had several hundred airfields around the country.

Before techniques were developed for taking off and landing on ships, the RNAS had to use seaplanes in order to operate at sea. Beginning with experiments on the old cruiser HMS Hermes, special Seaplane Carriers were developed to support these aircraft. It was from these ships that a raid on Zeppelin bases bases at Cuxhaven, Nordholz Airbase and Wilhelmshaven was launched on Christmas Day of 1914. This was the first attack by British ship-borne aircraft.

The outbreak of war

By the outbreak of war in 1914, both the Royal Navy and the German Kreigsmarine had very similar capabilities, in terms of technology, though not of numbers. They both had modern battle ships, battle cruisers, destroyers and submarines. The submarines proved to be the disruptive element which overturned the traditional naval strategy. The Royal Navy’s traditional action in time of war was to dispatch a powerful fleet to sit outside an enemy harbour and run a blockade. This could be tricky in Nelson’s time as ships were to subject to the vagaries of wind and tide. But the weather was of no concern to modern dreadnoughts. However a static fleet sitting on an enemy’s doorstep was an ideal target to submarines.

(Ships deployed anti-torpedo nets slung from wooden booms to protect against submarine attack. These provided some protection while a ship was at anchor, but they could not be deployed while under way at any speed, because they caused so much drag.)

As a consequence, the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet were both forced into a waiting game. If either fleet put to sea, the other could respond, relying on speed to avoid submarine attacks. One tactic used by the High Seas Fleet was to launch hit and run raids against English coastal targets. The aim was to entice the Grand Fleet into action, then the High Seas Fleet could retreat, sowing a minefield behind them as they went.

Minefields and countermeasures

Mines were cheap to deploy and expensive to remove. They were deployed across shipping channels to disrupt merchant and naval shipping. Trawlers were pressed into service to remove mines before specialist mine-sweepers were developed.

Anti-mine Paravanes were first devised in 1914 and developed through 1916. They are underwater gliders towed from a cable attached to each side of a ship’s bow. The paravanes pull the cable taut like a kite string. It the cable snags the mooring cable for a mine, the mine is diverted away from the ship and will explode harmlessly on contact with the paravane.

In an attempt to seal up the northern exits of the North Sea, the Allies developed the North Sea Mine Barrage. During a period of five months from June 1918 almost 70,000 mines were laid spanning the North Sea’s northern exits. The total number of mines laid in the North Sea, the British East Coast, Straits of Dover, and Heligoland Bight is estimated at 190,000 and the total number during the whole of WWI was 235,000 sea mines. Clearing the barrage after the war took 82 ships and five months, working around the clock. used to

The depth charge

In 1914, Admiral Jellicoe sponsored the design of an anti-submarine device. A standard anti-shipping mine was fitted with a thermostatic trigger which would cause the mine to explode at a depth of 45 feet (14 metres.) This mine was dropped from the stern of a ship, which had to be moving quickly to avoid being damaged in the subsequent explosion, “hoist by its own petard.”

By 1916 this device had evolved into the modern depth charge. It could be set to explode at depths varying from 50 to 200 feet (15 to 60 metres.) Production could not keep up with demand, so anti-submarine vessels initially carried only two depth charges, to be released from a chute at the stern of the ship. The first success was the sinking of U-68 off Kerry, Ireland, on 22 March 1916.

Monthly use of depth charges increased from 100 to 300 per month during 1917 to an average of 1745 per month during the last six months of World War I. By the end of the, 74,441 depth charges had been issued by the Royal Navy, 16,451 were fired, scoring 38 kills, and aiding in 140 more.

Coastal Motor Boats

In 1915 three junior officers of the Harwich destroyer force suggested that small motor boats carrying a torpedo might be capable of travelling over the protective minefields and attacking ships of the Imperial German Navy at anchor in their North Sea bases. Their suggestion resulted in the Coastal Motor Boat.

They were armed in a variety of ways, with torpedoes, depth charges or for laying mines, and carried light machine guns for protection. Designed by Thornycroft, they used adapted aircraft engines from firms such as Sunbeam and Napier. A total of 39 such vessels were built.

In 1917 Thornycroft produced an enlarged 60-foot (18 m) overall version. This allowed a heavier payload, and now two torpedoes or a single torpedo and four depth charges could be carried, the depth charges released from individual cradles over the sides, rather than a stern ramp. Speeds from 35–41 knots were possible, depending on the various engines fitted.

Aircraft Carriers

As well as sea-plane tenders, the Navy also worked on the development of aircraft carriers, the first was HMS Furious in 1917.

Originally laid down in 1915 as a large light cruiser mounting two 18 inch (457mm) guns, the largest on any Royal Navy warship.

In February 1917 her forward gun was replaced with a flying off deck.

In a remarkable event on 2 August 1917 Squadron Commander E.H. Dunning landed his Sopwith Pup on Furious’ flying off deck, the first aircraft to land on a ship. A few days later Dunning tried again but was killed when his aircraft went over the side.

As a result of Dunning’s accident a landing-on deck was built on the stern in late 1917.

The limitations of HMS Furious led to the introduction in 1918 of the first flat-top carrier with a full-length flight deck – HMS Argus.

top of page