Submarine Mines deployed in anger

| < 1906 – The end of the Submarine Mining Service | Δ Index | Electrical Control of a Mine > |

In all the years of the service from 1863 to 1906, the ability to deploy defensive minefields was a powerful deterrent.

Only once, in 1885, was the threat of war (with Russia) sufficient to trigger the readiness of mine defences.

In Singapore, the mines were loaded with gun-cotton, primed and made ready for immediate deployment.

In the Australian ports, the mine defences were actually laid out. This was the only recorded instance of this being done in any British port.

Mines deployed by the Royal Navy during WWI

Although the submarine mining service was disbanded in 1906, that was not the end of submarine mining. The Navy took over the activity again in 1914, and deployed controlled minefields in both WWI and WWII.

During World War I, the Navy deployed electrically-controlled defensive minefields at Scapa Flow, the Tay and in the Forth.

Controlled Mining in WWI

From “The Fortification of the Firth of Forth 1880 – 1977” by Gordon Barclay and Ron Morris- p57

“When, towards the end of 1914, it was realised that shipping was at severe risk from attack by submarines or raiders, the Admiralty proposed to revive the former system of controlled minefields, but this time under naval control. A new unit was raised within the Royal Marines, based on a cadre of retired former Royal Engineer Submarine Miners. The Royal Marine Submarine Miners came into existence on February 1915, with HQ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.”

The introduction of hydrophones – 1915

One of the reasons for the withdrawal of the submarine mining service in 1906 was the growing threat of submarines, which could slip undetected through the “friendly channel” in a controlled minefield. Various experiments were carried out to detect submerge submarines, including the use of aircraft.

Experiments were conducted from Carlingnose Royal Naval Air Station in 1913 which proved that a submerged submarine could be detected from an aeroplane by the wake which it created on the surface.

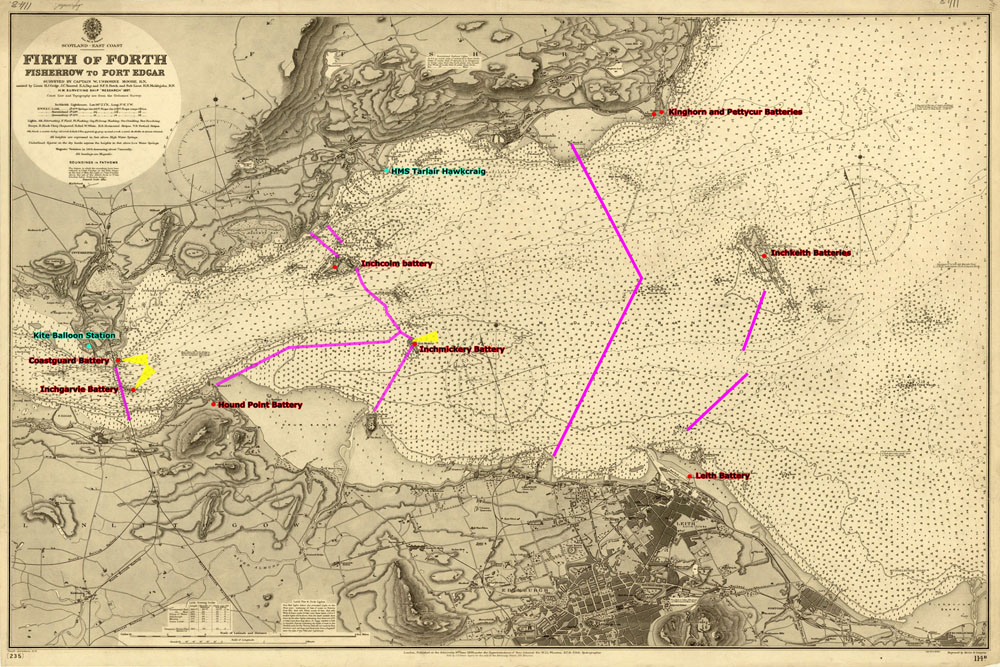

Further downstream at Aberdour, an anti-submarine experimental station was created at H.M.S. Tarlair. It focussed on detecting submarines using hydrophones – underwater microphones to detect the sound of a passing submarine. Hydrophone stations were established on Oxcars, Inchcolm and at Elieness in early 1915. However they were withdrawn later that year as they gave too many false alarms.

Experiments continued, technology advance, and by 1916, hydrophone stations were deployed on Inchkeith and Fidra and at Elieness, Crail and Seacliff.

Detector Loops

Another experiment conducted in 1915 at H.M.S. Tarlair detected submarines when their magnetized steel hulls passed over a submerged loop of cable. This proved to be very successful, but a report from HMS Tarlair was mis-understood, and it was not until 1917 that detector loops were deployed in anger.

The combination of a detector loop and a controlled minefield led to the sinking of a German Submarine off Scapa Flow in 1918.

Scapa Flow

From “Shield of Empire – The Royal Navy and Scotland” by Brian Lavery – pp212

“The first minefield in the base [Scapa Flow] was laid off Croo Taing, off South Ronaldsay, at the end of 1914, and it was intended to help close Water Sound to the east in conjunction with the sunken ships to seaward. It was made up of five rows comprising 166 electro-contact or EC mines. These could be detonated by a ship striking a mine, but could be made safe by electrical means from a watch-hut on shore.

The Cantick Field was laid the following month, across the passage between Hoy and the island of Switha. It had four rows, each of 18 EC mines.

Both these fields proved to be very difficult to maintain, because of strong tides. The electrical cables to the mines were constantly chafed as they went slack in falling tides, while on one occasion more than half of the Croo Taing field was accidentally detonated by strong currents.

A third EC minefield was laid at Roan Head in September 1916, at the northern end of the main entrance to the harbour.

The Houston Head field was laid out in the middle of 1915, across the eastern entrance to the Flow. It too was electrically controlled, but on a different principle. A hydrophone was used to detect submarines by the noise of their propellers and engines. An observer on shore would then press a button to detonate a group of the mines.

It had nine lines arranged in two rows. Each line had six mines and could be detonated separately.

A third row was laid across Houton in February 1916.

The second Observation minefield of this type was laid in December 1915, across Hoxa Sound, the main entrance for the battleships and cruisers. It was the most complex of the fields with three sections entitled X, Y and Z|, each with three rows which could be fired separately. Each row consisted of eight or nine lines of six mines, making a total of 156. It was the only one to see any action during the war. At midnight on 12-13 April 1917 the hydrophone station at Stanger Head reported a submarine, which was also heard at 2.30 am from Hoxa. At 9.20 next morning it was reported that the intruder was passing through the barrier and six mines of Y2 line were detonated; but no wreckage was ever found and no submarine was lost by the Germans.

At 10.21 in the evening of 28 October 1918 the Stanger Head hydrophones had another contact. Hydrophones suffered from the difficulty of being non-directional, so that the operator could not tell exactly where the submarine was; but in this case six operators in different stations worked as a team, comparing the intensity of sound that they heard. At 11.32 line X1 was fired and afterwards the wreck of UB-116 was found. This was the only concrete success by any British [electrically-] controlled minefield during the war, though there is no doubt that they acted as a deterrent to the enemy and gave reassurance to the ships anchored behind them.”

[Lavery cites his source as “Lockhart Leith, compiler, History of British Minefields 1914-1918, London c. 1920 ]

The Tay

From “Shield of Empire – The Royal Navy and Scotland” by Brian Lavery – pp250

“a controlled field of eighteen mines, which could be made live by an operator on shore, was laid across the relatively narrow entrance to the Tay at Broughty Ferry. It was done in too much of a hurry and they had to be raised in March 1915, and twenty-four larger mines were laid in their place in five lines.”

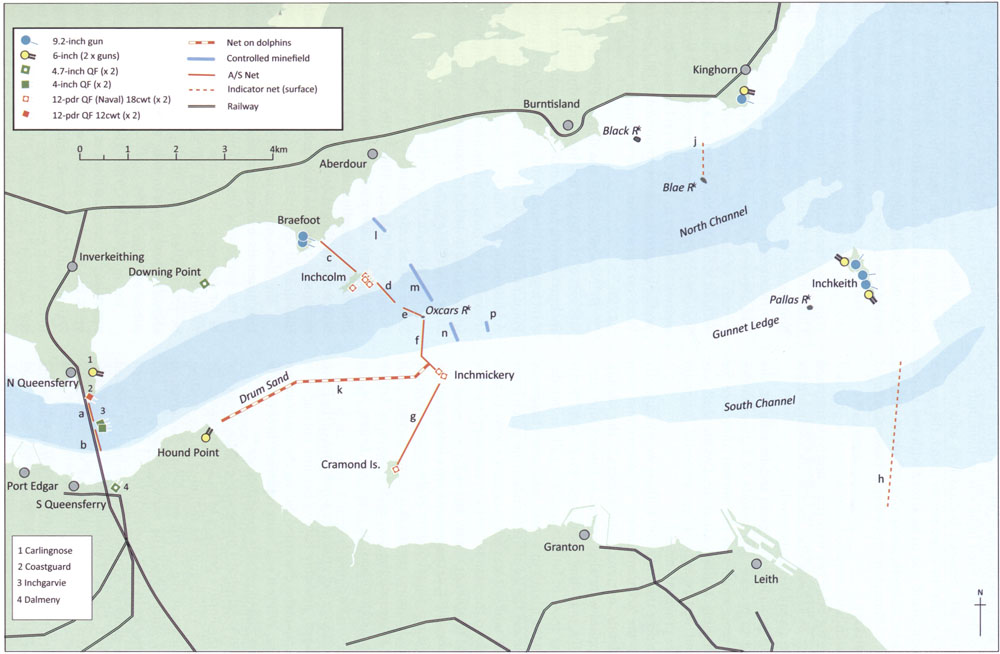

Firth of Forth

From “The Fortification of the Firth of Forth 1880 – 1977” by Gordon Barclay and Ron Morris- p54

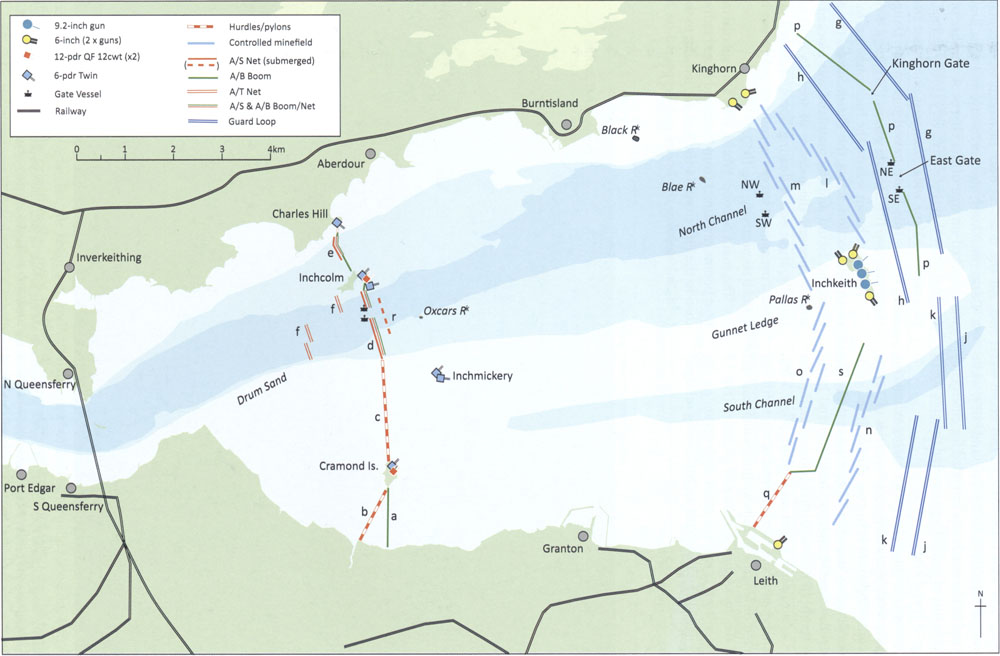

Three, or possible four, controlled minefields were established in the Forth controlled from Inchcolm and Inchmickery.

From “Shield of Empire – The Royal Navy and Scotland” by Brian Lavery – pp267

Clearing the minefields

“The observation fields were no problem, for they could be detonated by pushing a button, and the lines of mines at Houton Head, Hoxa, Mortimer Deep and Inchmickery were detonated for experimental purposes during February 1919, though two mines at Inchmickery failed to explode.”

The minefields at Inchmickery and Mortimer Deep were probably associated with the hydrophone station at Hawkcraig, Aberdour.

[Lavery cites his source for all three articles as “Lockhart Leith, compiler, History of British Minefields 1914-1918, London c. 1920 ]

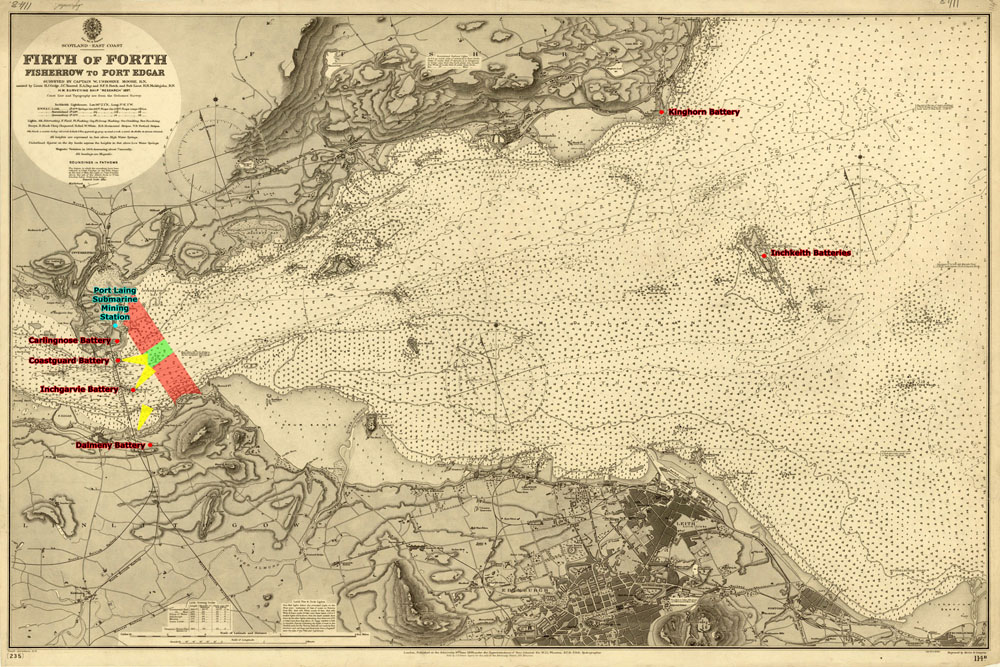

The evolution of the Forth Defences

The Forth defences evolved into a multi-layered set of anti-submarine defences, with anti-submarine nets strung across the river at several locations, and gun batteries further downstream.

Forth Defences in 1901

Anti-Submarine nets were hung from the spans of the Forth Bridge, and strung across lines of dolphins further downstream. Gates in the net could be opened by armed trawlers.

The battery on Carlingnose Point was built between May 1899 and July 1901 at a cost of £7856 1s 9d. Two 6-inch guns were mounted in 1902 and remained in place until 1916. Following a large scale revision of the defences of the Forth it was decided that the two 6-inch guns should be moved to the new battery at Pettycur, Kinghorn, and the guns were transferred in November 1916.

Two Maxim .303 machine guns remained to defend the battery, which continued to be the site of the Fire Control Post of the Inner defences of the Forth.

The battery at Inchgarvie was built for two 12-pounder guns, between June 1900 and October 1901, at a cost of £2826. It took the form of a single block of buildings to the west, with the two guns on the same overall platform to the east. This was the armament of the island on the outbreak of war in 1914.

In April 1914 proposals had been approved to increase the armament of the battery to four 4-inch guns, with three defence Electric Lights – large searchlights to illuminate targets for the guns at night.

Two new gun emplacements were added to the east of the existing pair, and a new engine room was to be built at the west of the existing block of buildings. The two 12-pounders remained in position until the 4-inch guns were ready, and then they were replaced by two further 4-inch guns on special mountings to fit on the 12-pounder emplacements [The National Archives WO 192/108]. This was done by September 1915.

The two 12-pounders went to the Coast Guard battery.

In 1916, the 4-inch guns (Mk IIIs) were moved to Inchmickery and replaced by four 12-pdr Quick Firing (18cwt) guns. The fort had two .303 Maxim machine guns for close defence against enemy troops.

In the end (1917), the island was armed with four 12-pounders. It also finally had five Defence Electric Lights, although running more than four at once would overstrain the generating engines.

The guns were removed and returned to store in May 1920.

The battery had an establishment, on mobilisation, of 4 officers and 61 other ranks, which rose to about 90, with a detachment of 44 Royal Engineers for working the Defence Electric Lights and the telephone. Medical cover was provided by a RAMS Orderly from Edinburgh Castle.

Forth Defences in 1918

1919 – 1938 Development of Submarine Mining Technology

From “The Fortification of the Firth of Forth 1880 – 1977” by Gordon Barclay and Ron Morris- p69

In 1928 and again in 1932, the area between Canty Bay on the East Lothian coast and the Bass Rock was used to test new developments in controlled mining. NO controlled minefield or detector loop had been laid since the end of the war, and officers and ratings had little practical experience. . . By the end of 1931 these experiments showed that loops and mines laid by trained personnel could obtain a high level of detecting efficiency.

This led to the introduction of a “Controlled Mining Handbook” in 1938, which recommended that mines were laid in a “standard 16-mine-loop”, consisting of a string of mines laid within a detector loop.

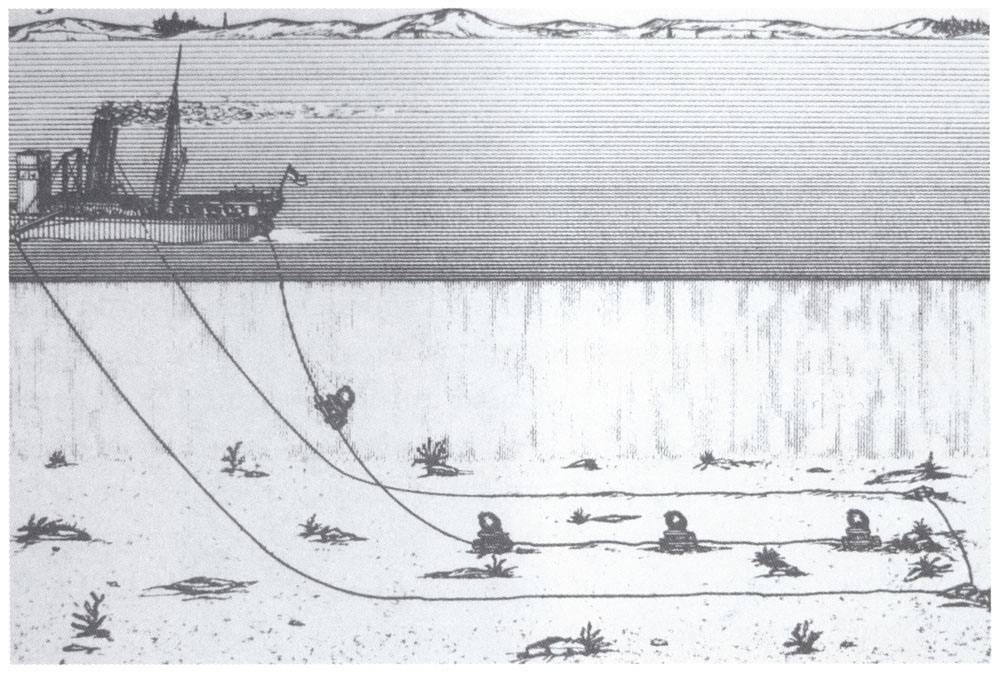

This diagram shows how the mines and detector loops were laid.

Many of these loops were deployed in the Forth by 1942

They were controlled from portable control stations consisting of a control hut, a power hut containing engines and batteries, and a telephone.

A rather different set-up to the pre-1906 station at Port Laing.

| < 1906 – The end of the Submarine Mining Service | Δ Index | Electrical Control of a Mine > |

top of page