War time defences in Collesie and Fife

On Wednesday 15th May 2013, Steve Liscoe from Fife Archaeological Unit presented a talk on wartime defences in and around Collessie and Fife at Collessie Village Hall.

Steve very kindly gave them permission to reproduce his talk so that anyone unable to come along to the talk is able to enjoy the fascinating facts and events in Fife that Steve talked about.

[Steve’s talk discusses the Fife Stop-Line. See Gordon Barclay’s Paper for more details on this topic.]

“The Enterprise and Protective Services department, including Douglas Spears and myself, are employed to help to ensure that the archaeology of Fife is protected. We consult on planning applications which may have an effect on archaeological remains which may already be in place, or which potentially could be in place, so that the archaeology of Fife is protected as much as possible and preserved at least by record, if not physically.

The Archaeological Unit maintains the Fife Sites and Monuments Record, which is a register or index, and is a record of every known archaeological site in Fife, that we know about, comprising of around 13,000 individual entries.

We refer to this record to determine what remains may be at a particular site, or potentially what may be at a site, that we need to consider. A condition can be placed on the developer, for example, asking them to consider what may be there as they develop a site.

This information has now been digitised, so that we can interrogate the information, and use it as necessary, and update it as new sites are identified.

We all know the comedy series ‘Dad’s Army’ and this series portrayed the threat to the south of Great Britain from the continent, but there was just as much of a threat to Fife. The whole of the continent was occupied by our enemies, from the low countries to Scandinavia, which is a lot closer to us that you might think. If it weren’t for the curvature of the earth, I could probably see Denmark from my home on a clear night!

Fife’s geography lent itself very nicely to a sea-born amphibious invasion. If you think of Normandy with its long, flat beaches, here in Fife we have a lot of the same beaches, so it was a real threat, and a hostile force landing in Fife would be able to go from East to West very easily, and would be able to cut Britain in two, something that nobody wanted to happen. So that was why we had such a serious concerted effort to defend Fife.

The Germans knew that as well as we did, and they had made reconnaissance of our defences long before the war started, and aerial reconnaissance pictures exist of the bridges crossing the Forth. The pictures show notes, highlighting the military targets of interest, vessels involved in maritime defence of the Forth, and a coastal defence battery at Carlingnose, with twin 6” pieces of coastal artillery.

The pictures show the wartime splinter camouflage painted onto the concrete gun decks, which served two purposes – It broke up the look of the decks, so that it couldn’t be picked out so easily in aerial reconnaissance, and also gave the garrison something to do to keep them busy!

This small coastal battery was equipped with facilities for the garrison that manned the guns, instruments, and a whole host of support facilities for what seemed a relatively small defence structure. This battery at Carlingnose is very well preserved, and is actually a scheduled monument, which means it is protected in law against anyone interfering with it.

Carlingnose Battery

Carlingnose Battery

Unfortunately we are unable to ‘preserve’ sites such as this because that is proactive, whereas our role is that of preventing damage, and protecting development of these sites.

The outlook from one of these gun placements is a very clear line of sight down the Forth. It was built in 1905 because at that time any invasion would have come from the sea with a naval assault and an amphibious landing. So coastal artillery was the primary deterrent for anything like that, and if a warship of a belligerent nation were to try to sail up the Forth, a ring of these defences would be able to defend us as soon as they got within range.

What were they defending, apart from stopping an invading force? The dockyard at Rosyth was built at the same time, which was commissioned and completed in 1915, which made it a primary strategic importance, being a large naval base. Control of the seas at that time was a crucial factor in defending our shores, and the Luftwaffe were very interesting in seeing our bases and our defences – what were they up against if, or when, they attacked our defences.

But the defences of the Forth and the dockyards started a long way out to the East, at the Isle of May. There were no guns on the Isle of May, just a naval detachment and a naval establishment which was a crucial part of the defence of the Forth. The building on the Isle of May, was a war signalling station, and contained staff with sharp eyes and ears watching all maritime movement, observing all shipping movement, recording details and sending information, first of all by semaphore and then by wireless, back to the mainland to report on the activities they had seen.

The building had stood there for around a century and was re-used as an observation station by the RSPB, but the building burnt down and was demolished. But the other defence system that superseded this signalling station defence system was a series of underwater hydrophones, or underwater microphones, which were laid on the sea bed between the island and the coast near Crail.

On the island were a set of highly skilled staff who listened to sounds on these microphones, and they could distinguish between a seal, a whale, shoals of herring and all manner of underwater sounds, including submerged U-boats, which was the main threat. Surface vessels could be easily spotted, but U-boats needed sophisticated technology to track them.

It was a very intense job and the staff only worked in 2 hours shifts because the concentration needed was such that after 2 hours they would be exhausted and needed a 4 hour break. In the Second World War, technology had moved on, and the defence system used was not microphones on the sea bed but large loops of copper wire that had an electric current running through them that created a magnetic field in the water. Any large object or steel object, or a U-boat, would cause an effect on the instruments which could be reported. If it wasn’t on the list of friendly shipping movements for that day, you could assume that it may be hostile, and boats would go and intercept it and deal with it accordingly.

During the second world war, the emphasis changed, and while amphibious assault was still a prime concern,

airborne assault was considered more of a threat, and we were at mercy of an attack from the skies, and a new commander went out to the Isle of May, and he assessed all the systems in place such as the microphones on the sea bed and decided that it would only take an aircraft strafing the building or even an indirect hit from an aerial bomb to destroy this defence, so he brought out building materials to the Island, and built a blast wall around the wooden shed to protect it from attack. It wouldn’t protect it from a direct aircraft hit but it would protect the men and building from machine gun fire from an aircraft and aerial bombardment. Simple, but very effective, and so simple that the new structure only needed 3 sides as the back of it was against rocks, so already protected on the fourth side!

Unfortunately, it is not there today as SMH who run the Island, demolished the building on health & safety grounds, and turned it into hard core for pathways on the island.

Isle of May Loop Building

Isle of May Loop Building

But what you can see out there today is interlocking iron collars, a kind of ball and socket cast iron collar, which houses the cable where it came ashore, which protected it from the harsh elements as it ran up the beach to the induction loop monitoring station.

Where that system came ashore, at West Ness which is just west of Crail, there is a building which is all that’s left of the end part of this system as it came ashore.

One of the most important islands in the defence system was Inchkeith, which was covered in buildings and trenches and features which showed it was a highly important military defence centre.

Inchkeith Maritime Command Building

Inchkeith Maritime Command Building

One of its most important features, apart from the lighthouse which is still there and now functions automatically, is a very plain brick building and has large areas of just plain concrete plinths. The building was the command centre for the whole maritime defence system on the Forth, and this is where all the intelligence gathered around the area by guys with binoculars, radar stations, induction loops, and anybody who had any intelligence information, was analysed and actions taken.

Now, what is so important about the concrete?

During the war, the garrison on that Island could be up to 900 people. Most chaps liked cups of tea, which needs water, and there were only 3 springs of fresh water on the Island, so if the water bowser didn’t get out to the Island because of bad weather, to replenish their water supply regularly, they could run out of water very quickly. So what these concrete plinths did was act as a water catchment system so that when it rained, the rainwater was captured and channelled into underground and above ground rainwater storage tanks so that they had enough water on the Island to keep them happy.

The command Centre building is now, unfortunately, derelict, but the whole of the Island is actually a Scheduled Monument, a fact that was probably overlooked by Tom FARMER, from Kwik Fit, who planned to turn the island into a corporate entertainment facility, but obviously this was not allowed to happen because Historic Scotland holds it in protected status.

At the north and south end of the island are 6” gun batteries, virtually the same as those at CARLINGNOSE, but over the back of the ones on this island, there is a 1940’s defence against aerial attack. The gun was protected by a cover at the back by a simple brick apron and roof built around the back of the gun placement which could give a good defence against aerial assault.

Inchkeith

Inchkeith

Along the spine of the island, the larger guns in bigger buildings housed 9.2” guns with a range of 22 miles, which were extremely effective as a deterrent as they could engage any amphibious force 22 miles before they got to their target.

Because the Germans were so good at aerial assaults, measures were put in place to repel any forces landing on the island, but these guns were defensible in their own right, by the gun loops in the blast wall. The rest of the island could be over-run but the guns could still operate very effectively in isolation.

Not only does the concrete and steel remain on the island, but on the inside of one of the buildings, there are coloured coded images of bombs, which would remind the soldiers as to which bomb should be used in the event of an attack.

In the heat of firing the gun, confusion can cause mistakes to be made, so having a visual image to check by the gun was very useful.

With 900 soldiers and personnel out there, the island was a community in its own right, and was, in effect, a small town, with a whole gambit with things like canteens, barbers, doctors, infirmaries, doctors, billets, dormitories, etc. All this remains out there on the island.

But those defences again are not just Second World War defences, or even First World War defences. They date back to 1880, and the original guns out there were Victorian, as can be seen on the inscription on a building that shows V 1880 R. But on the east side of the island, there is a strange angle in the wall below the lighthouse. You can see a gun loop which is 16th Century, and there was a 16th century fort built on the high ground on the island, so the strategic importance of Inchkeith dates back several centuries.

In the 16th Century, the fort was garrisoned by the English, and kept the Scots subjugated, so the Scots brought French mercenaries over, who landed on the island and killed the English troops on the island, and were told to demolish the Fort. Luckily the French mercenaries were not very good at demolition, so substantial parts of the Fort still remain today for us to see.

The Forth has got a number of islands conveniently placed to give an artillery barrier across the Forth to defend the dockyards at Rosyth and Leith, and other important ports.

Inchcolm has 6” gun emplacements; Inchgarvie had anti-aircraft guns and searchlight emplacements. Others had anti-aircraft defences for the bridge and the dockyards. The searchlights worked in support of the guns, so that if there was an amphibious assault at night, there was nowhere to hide.

The huge carbon-arc lights would light up the whole width of the Forth because of the position of the lights on the north and south sides as well as the islands.

Seahaven Fort 6″ Coastal Gun

Seahaven Fort 6″ Coastal Gun

On the Fife side at Charles Hill, there is a 6” gun pit and search light batteries which operated in conjunction with each other.

Coastal Artillery Searchlight – Charleshill

Coastal Artillery Searchlight – Charleshill

Other underwater defences during the war were minefields, floating booms and submarine nets lying on the sea beds. The submarine nets were hung in the water like curtains, so that if submarines tried to come through unseen, they would be prevented from sailing up the Forth. During the war, two main navigable channels on the Forth were kept open, and they could be controlled and monitored and shipping was allowed through if authorised.

Mines were fixed, and consisted of explosive charges laid where an assault could be anticipated, and in times of warfare, you need to be able to land troops at a port. Ports were defended by fixed explosive mines on the seabed, and if an invading force tried to come in, a switch could be flicked and the sea bed would explode underneath them.

Between Anstruther and St Andrews you pass buildings in the corner of the field. The buildings are radar stations, and formed the first radio station in the UK to be integrated as part of the UK air defence system. Information from this radar station would be fed back to the Maritime Commander at Inchkeith. It’s on high ground just north of Anstruther.

But it wasn’t looking for aircraft. These radar buildings were aligned so that it looked at the approaches to the Forth and the North Sea. It was looking at shipping and picked up surface targets and again if they didn’t correspond to known shipping movements, it was assumed they were hostile and action could be taken and they would be intercepted. A prime target to look for would be a surface U-boat.

So this was a naval radar station. A story from one of these particular buildings goes that from the moment the farmer had notice his fields were going to be requisitioned as part of the war effort to the moment the radar went live, it only took 2 weeks to build the radar station building.

The only things that went wrong was that the man who commissioned the boiler in the canteen put the flue in the wrong way round, and nearly asphyxiated everyone in the canteen the first time it was lit.

But what were they defending?

Fife was an extremely important area in the UK as it had a lot of industry that provided materials for the war effort. For example, Nairn’s (who everybody knows as a lino manufacturer) and any manufacturing industry at the time geared itself up towards producing goods for the war effort.

Fife made munitions, more than we could ever imagine – aircraft components, aircraft sub-assemblies, aircraft fuel tanks, merchant ships, warships, small patrol vessels, and a lot of military research going on in Fife with experimental stations, bases in Fife for training and operations, and it was very important to protect it.

Turning home-grown industries in Fife was therefore very important, and an important supplier was Nairn’s.

Nairn’s Factory

Nairn’s Factory

Nairn’s made grand-slam and tall-boy bombs, which were massive, weighing in at 6 tons and 12 tons a-piece. These were formidable weapons at the time, their purpose was to not just create a huge explosion – they would penetrate reinforced concrete to some depth and would then penetrate the ground to some depth before they exploded.

They were called the ‘earthquake’ bomb and if they went off underneath, for example, a building, they would liquefy the ground with the explosion and anything on top of it would be destroyed. They had a huge destructive potential.

Conventional bombs dropped on U-boats caused little damage – a few paint chips here and there, but a tall-boy could penetrate 25 feet of reinforced concrete. A huge factory and launch site in Northern France was destroyed by a tall-boy. Aerial attacks tried to sink huge warships unsuccessfully, but the tall boy would hit them and destroy them very effectively.

The importance of that particular weapon was huge, and the casings for those bombs were made here in Fife.

Incidentally, the air-crews in charge of these tall-boys were told that if they were unable to drop the tall-boys, they were to bring them back again so that they could be taken out again another time. This was different to a normal load of bombs, where the advice was always to drop the bombs, even if the original target couldn’t be identified or was missed.

Landing an aeroplane with a bomb on-board was not accepted practice, but the huge cost of manufacturing the tall-boys made them too valuable to use up on ordinary targets which could be hit with normal bombs.

We still have a number of airfields in Fife and one was not a combat airfield, it was a training airfield, and was a naval station known as HMS Jackdaw.

Anyone who had anything to do with flying aircraft off naval carriers were trained how to do the role here. The aircrews, the ground crews, the fitters and support personnel were all brought here to train. The airfield control tower is a scheduled monument, and uniquely the control tower had four storeys.

RNAS Control Tower

RNAS Control Tower

Another important building on the airfield was a corrugate-roofed, which inside looked like an open doughnut, and was in fact a 1940’s s flight simulator. It was the only one in the world, and was called a Torpedo-Attack Trainer.

It had a seascape painted on the inside which looked very realistic, and had a series of projectors in the roof at the centre which projected images of ships and aircraft onto the walls to simulate real-life warfare, to enable staff to train in what they may have to experience during a real attack.

In the centre of room, there were be a member of staff in a link trainer, which was a flight simulator, and he would be trained to attack moving ships with a torpedo.

Torpedo Attack Trainer at HMS Jackdaw

Torpedo Attack Trainer at HMS Jackdaw

It was a unique training tool, and when America entered the war in 1941, their fliers came to Crail to learn tips on how to carry out effective naval flights, and when they saw the simulator, they were so impressed they took away all the drawings to Pensacola where they did their training, and built one of the simulators to do the same job for their navy pilots, and they called it the ‘Crail Trainer’.

Another airfield was called HMS Jackdaw 2, which was a satellite airfield for the Crail airfield, which had a smaller control tower and had a grass runway, and hangers are still there which are used by the farmers for storing farm machinery.

Nissen huts were flat-packed (well, with a curvy top) and were delivered flat-packed and assembled quickly and easily on-site. The original purpose of some of these were as radio stations, with masts, listening to U-boat transmissions in the north sea and any other enemy surface transmissions – Enigma-coded transmissions, which were recorded and sent down to Bletchley Park where the decrypting station there deciphered and de-coded the messages so that we knew exactly what the enemy was talking about.

The intelligence war also started here in Fife – up at Tentsmuir at Leuchars, a series of decoy buildings were constructed and named a Q site, or decoy site, which were used to confuse aerial attackers who were looking to bomb the Leuchars airfield.

A couple of miles north of Leuchars so that if a bombing raid was coming over from Norway and it looked likely that Leuchars could be the target, Leuchars would go quiet and stop all unnecessary activity, everything was blacked out and meanwhile a few staff would go into the decoy buildings, start the generators and they would start a series of lights across the flat moorland to the south of Tentsmuir, which simulated aircraft moving down runways, aircraft moving down runways, doors opening and all the sort of activities which a German aircraft would expect to see from an airfield.

But the real target was a couple of miles away and the enemy aircraft would drop bombs two miles away from their real targets, and these decoy sites were very effective in preventing attacks at our military bases and strategic targets.

Up at Tentsmuir there was a big flat beach, giving a prime site for an invading force, so it was heavily fortified against enemy invasion and amphibious landing. During the war, Poland had been over-run by Germany and the Soviet Union, but a lot of Polish nationals had escaped to Britain, and had lost their country so were willing to fight to take it back.

A lot of Polish people were recruited into our armed services, trained and prepared to go back to help to liberate and re-occupy their own country again when the time was right. Tens of thousands of Polish people built most of the concrete obstacles and fixed defences that were such an important part of our defence system against invasion.

Their contribution was so important that General Sikorski, the leader of the Polish Forces in exile, made an inspection of the sites with the King and Queen.

At many, many places around the coastline you will see the concrete tank obstacles, weighing at around 3 ½ tons each, along with pill boxes, and they created a very effective obstruction to vehicles wishing to drive up on the beach.

Earlsferry Blocks

Earlsferry Blocks

But also up at Tentsmuir, you get very strange remnants of defences, such as what looks like a sand pit, still there and recognisable 70 years after it was created.

Down at Pettycur Sands, at Burntisland, there was a lovely, flat open beach when the tide was out, great as a beach for enemy aircraft to land on. So defences were needed to safeguard the beach, and especially against very effective glider assault. To defend against this type of assault, pieces of telegraph pole were sunk into lumps of concrete on the beach, giving a very effective deterrent to gliders, which would be broken up on impact with these poles.

Polish Troops constructing beach defences

Polish Troops constructing beach defences

Discreet defences were dotted around the coast, such as machine gun embrasures in sea walls and piers, which could easily pick off any invading forces coming from the sea. The sea front wall at St Andrews has a machine gun embrasure in the sea wall, looking straight down the West sands.

And again, in the ground behind it, there’s a pillbox. But even with all these coastal defences, if the Germans had wanted to invade us from the coast, they could have done it. Our coastal defences would have been a nuisance to them and would have delayed them, but wouldn’t have prevented an invasion as it was not an impenetrable defensive system.

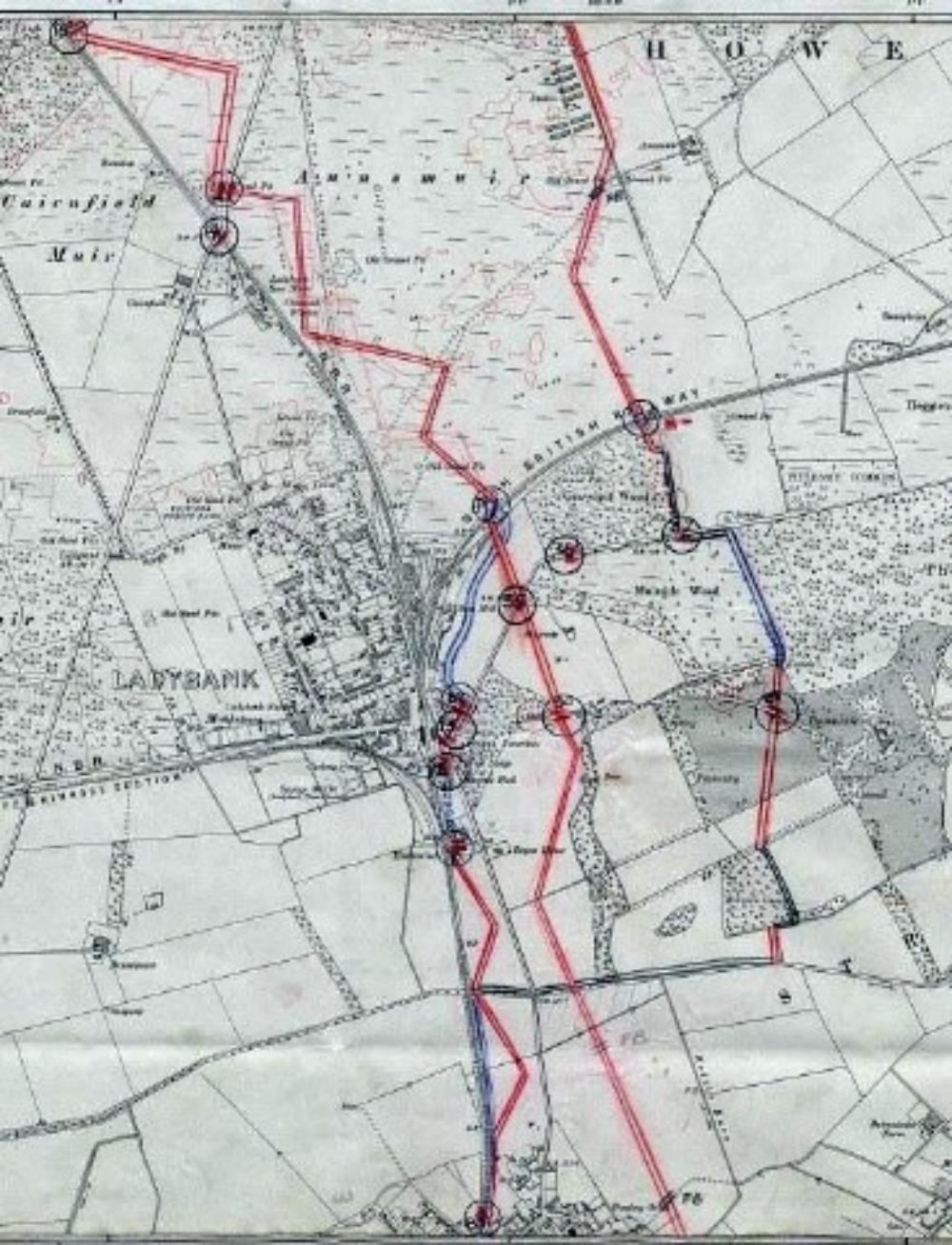

So, halfway down Fife we had the real defence – a very large complex of anti-tank measures – bunkers, pillboxes, minefields, search light emplacements, barbed wire entanglement, road blocks, rail blocks – the whole range of measures designed to halt any invasion.

And the most important part of it was what looked from the air to be an irrigation ditch. Looking at it closely, the beach is on one side, and coming along from this direction, there was a nice gentle slope leading down into the ditch. And then you come up out of it, and the slope on the opposite side is appreciably steeper.

In 1940, this was a very effective anti-tank, anti-vehicle defence. A vehicle and troops could get into it, but getting out of it was extremely difficult.

Kirkforthar at the ditch

Kirkforthar at the ditch

These ditches, sometimes two or three deep, ran from Newburgh down to Dysart, the whole width of Fife from north to south.

It was called a ‘Stop Line’ and its purpose was to stop the invading force once they had breached the coastal defences, and prevent them from going any further until you had time to muster your forces and bring them to bear and repel that invading force.

Fife Stop Line

Fife Stop Line

So this, again, was a stop-gap defensive measure while the main forces were massed and could be brought to Fife to deal with the invasion. This ‘stop line’ also continued upwards towards Perth and Kinross.

See Gordon Barclay’s Paper for more details about the stop line.

Natural features such as railways embankments provided natural obstacles to invading forces, which was a good anti-tank measure, road blocks and rail blocks were used and woodland was another natural barrier, so the stop lines used natural features of the land to enforce its effectiveness.

The stop lines were mainly cut across farmland, so when the hostilities were over and the land was returned back to agriculture and farming, the earth that had come out to create the ditches was put back in by the farmers, so the vast majority of the stop-line ditches have disappeared.

Collesie Stop-line features

Collesie Stop-line features

Because the geology wasn’t suited to digging ditches around Collessie, concrete “dragons teeth” were created across the fields around Collessie instead of creating ditches, and even though they look as though they are placed very regularly in the land, the distance between the “teeth” was very carefully calculated so that it prevented vehicles from being driven over the top of the “teeth”.

If vehicles did manage to drive over the top, they would possibly topple and break on impact, and it would break the tracks and suspension of the vehicles and just as importantly it would expose the underbelly of the vehicle so that guns in bunkers placed strategically through the area could pick off the invading forces.

Collessie Dragon’s Teeth

Collessie Dragon’s Teeth

So when you see a pillbox or feature in the middle of a field, it could well be part of the stop-line defences set up to defend Fife again hostile invasion.

Angle Park Type 24 structure

Angle Park Type 24 structure

Little remains of the stop lines, except for the solid concrete and brick structures, and occasionally you will see remains such as the surprise holes in a bridge wall, which housed soldiers with guns who were there to ambush hostile forces.

The Home Guard manned a lot of these defences, but they were only lightly armed. When the British Army had left Dunkirk, they left behind all their heavy artillery and anti-tank weapons, guns, etc. so we had lightweight artillery.

But we made do with what we had at the time, and there was nothing that couldn’t be commandeered into defending Fife. Road, rail and bridge sections were important routes to defend, so holes could be cut into dykes, pieces of telegraph poles or railway track were put it to support the masonry and there you have a secret spot to defend the bridge or roadway. Guns were mounted in cemetery walls, so nothing was sacred when it came to the war effort and defence of Fife.

Some road blocks were temporary as we couldn’t block off all major routes, so instant road blocks were created out of pieces of bent angle iron which were inserted into the road at one end and bent over to form an impenetrable and easily defended road block, which could be moved relatively easily if needed.

If the alarm was sounded, sandbags could go up, the angle iron road blocks could be used, rolling lumps of concrete into the road, etc. – things were made up as needed to defend areas with whatever materials came to hand.

And searchlights were used, not just against coastal artillery, but used on land. If there was assault at night you wanted to illuminate your target so that you could defend the area from your bunkers or pill boxes or road blocks. So part of the defensive line was search light emplacements.

And you would think that we would know where all these were located, wouldn’t you?

A short while ago we were excavating an iron-age farmstead on the top of a hill, and we kept coming across beer bottles and bits of metal and investigation showed pieces we found came from a barbed wire barricade from the 1940’s. We wondered what had been there until we came across a couple of carbon arc rods, which were from the two arc points that were used to generate the light in the searchlights, so what we had come across was a search light emplacement, right in the middle of this iron-age site that we had no idea existed there.

You do come across steel observation boxes & pillboxes up at Tentsmuir, and there are a number of these surrounding the airfield at HMS Jackdaw at Crail.

HMS Jackdaw II Control Tower

HMS Jackdaw II Control Tower

There are a number of strange looking structures in Fife, which were created as flat-pack structures, erected on site. One such structure looks like a dome with holes around it for guns to be fired from inside the structure. But it doesn’t look that strong, until you look closely, and you realise that the structure is double-skinned and inside the outside structure, you can see there is another dome, with a gap of 3 – 4″ between the two domes. That makes the structure bulletproof – all the energy of the projectile would be spent penetrating the outer skin and it would then be stopped by the inner skin, making it bulletproof to small arms’ fire, but I bet it would make your ears ring if you were inside it when bullets were fired at it!

Dome at Tentsmuir

Dome at Tentsmuir

You also see concrete block buildings which have a pin, or spigot, inside the centre. Anti-tank weapons had all been left in France, but this was built as a spigot mortar, and it fired projectiles which was particularly effective as an anti-tank weapon. It was effective at 100+ yards but you could create these very quickly, and they were a stop-gap weapon until the factories started producing proprietary anti-tank weapons.

Spigot Mortar

Spigot Mortar

Miles away from any targets of strategic importance as far as defending them goes, we have reservoirs such as the one north of Kennoway, now a nature reserve. Why would you possibly spend any effort defending the reservoir, miles away from any major town, in the middle of Fife?

Well, its water and you could land seaplanes or airplanes and gliders with floats on this stretch of water, and troops landing here were just as unwelcome as those landing on the coast.

The defence of these stretches of inland water was very simple. Two steel poles, usually railway lines with a toggle set into it were located either side of the water, and a wire was anchored between them, so anything landing on the water and hitting the lines would be severely damaged.

Making air assaults, you would want a large open area to land aircraft or gliders and land troops, and our airfields, while giving us somewhere to launch our planes and land our own troops, were also open to being used against us for air assaults. So they had to be defended and re-in forced concrete pillboxes were built on the periphery of the airfield.

But unlike normal defence structures outside of the airfields, they had gun embrasures which faced inwards, because the airfield had to be defended with guns facing inwards towards enemy troops landing in the middle of the runways.

We never had any aerial landings or assaults in Fife, but a lot of Germans did come to Fife, and stayed in a number of prison camps, and were captured from surface vessels, sunken U-boats aircrews captured when planes were shot down, Italians as well were there. A couple of the prison camps are still surviving today, one at Bonnytown south of St Andrews where you can see billet huts and plinths as well as latrine blocks.

These buildings were built around 1940, and are very well preserved considering how long ago they were built. Farmers have used them for storage over the years and it says a lot for the quality of workmanship that these buildings can still be seen today.

Prisoner of War Camp at Bonnytown

Prisoner of War Camp at Bonnytown

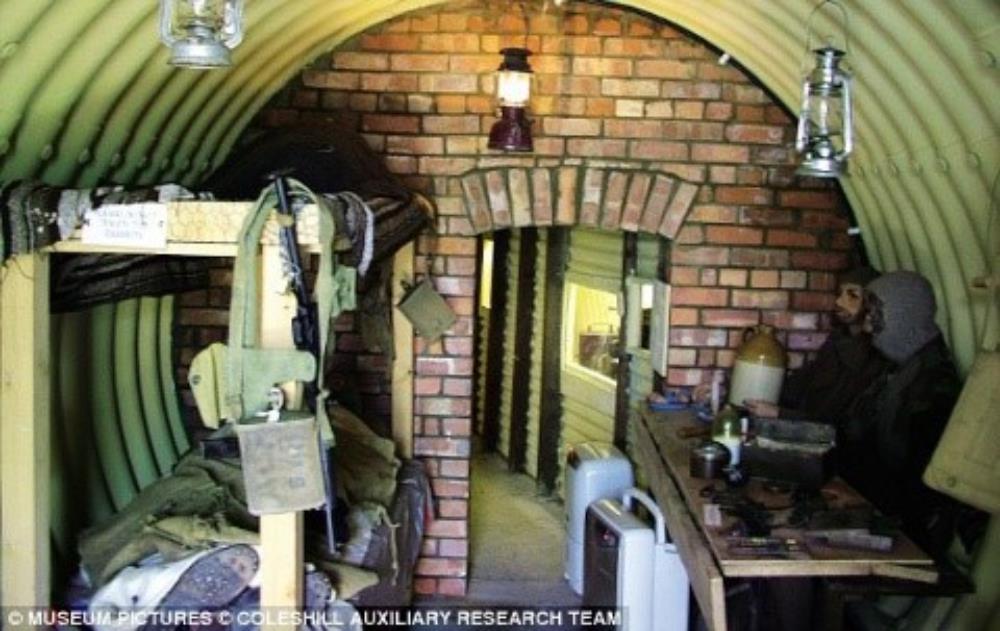

Had we been invaded, we would have been in trouble. But one secret weapon we had was, in effect, part of Dad’s Army. Known as the Auxiliary Patrols, they were men who were recruited from the Home Guard because of their local knowledge. They were what is commonly referred to as the ‘British Resistance’.

They were trained in the latest methods, given the latest specialist equipment even before regular troops were issued with it, given specialist training in explosives, demolition, sabotage, and they were dangerous people.

Their function was when the invasion happened, they would all go and hide in what was called an ‘operational base’ in secret underground bases where they would go to ground in groups of around 6 men at a time, and they would be over-run by the invading force above them.

Auxillary Unit Operational Base – Replica

Auxillary Unit Operational Base – Replica

After a day or two, when things had settled down above them, they would come out and literally create as much havoc as they could, and make an absolute nuisance of themselves, cutting enemy communications, blowing up vehicles, destroying whatever they could to hamper the invading forces to the best of their ability.

They had a life expectancy of 2 weeks before they were caught and executed. Their bases were so secret that we still don’t know where they are. In the Sites and Monuments Records, I know of only eight records of these operational bases, and I know of the actual location of only 5 of these. We only find them by accident where many, many years later the corrugated iron roofs collapse under the weight of soil and undergrowth and reveals the bunker underground.

We know that these underground bunkers were equipped with all modern conveniences such as dehumidifiers, and would contain real home-from-home comforts.

At Melville Lodge we know there is a bunker, but we don’t know where. What gives us a clue to the existence of a bunker there is a tree in the grounds, which has a long groove cut vertically into the tree to take an aerial for a radio transmitter.

We have another building which has a covert purpose – at Pitreavie Castle there is a building which looks ecclesiastical in origin – a church or chapel perhaps, which is in fact a big generating building. A lot of pillboxes are built around the perimeter.

Pitreavie Castle, south of Dunfermline, was the headquarters for the RAF operations in Fife. The most interesting part is what lies beneath the tennis courts at the back of the main building. In 1937 a bunker was built there, which is 3 stories deep. It housed the command centre for all the maritime operations in the northern hemisphere.

The RAF had a presence in there with their coastal command operations, overseeing the maritime patrols, defending convoys and searching for U-boats. The Navy were there, with warship operations, convoys for trade routes to North America, Nova Scotia, and the Arctic convoys.

The Royal Observer core were there and anything to do with maritime operations in the northern hemisphere were operated from this bunker in Fife. The bunker was in operation until 1996 doing the same job, which means that our nuclear submarines – Polaris – were controlled from this bunker in Fife.

At that time, all the defences we have looked at today were not effective in the event of a nuclear strike. There are a few defences still remaining which would have detected a nuclear attack, and all that can be seen above ground is a ventilation shaft which signified a Royal Observer core monitoring post.

You would go down a small shaft into a single-room bunker below ground where a detachment of 3 men would sit and monitor the outside environment in the event of a nuclear strike.

They could determine where the bomb went off, the strength and the level of contamination, and this information would be sent back to the Command Centre at Pitreavie and also fed into the civilian centre at Troy Wood where civilian control would be maintained in the event of a nuclear strike. There is an excellent example of one of these bunkers at the Elie Golf Course, which is used as a store for the golf course.

It is maintained and kept in good condition, and a window has been painted on a wall inside the bunker which looks very realistic. The Golf Course boasts that it has the distinction of being the only golf course to have an authentic ‘bunker’ on its golf course!”

If you have any questions on Steve’s talk on wartime defences around Collessie and Fife, please contact Steve using the details below:-

Steve Liscoe

Professional Assistant (Archaeology)

Archaeological Unit

Enterprise, Planning & Protective Services

Regeneration, Environment & Place

Fife Council

Floor 2 Kingdom House

Kingdom Avenue

Glenrothes

KY7 5LY

Direct dial: 01592 583391

VOIP: (08451 55 55 55) Ext. 473777

Fax: 01592 583199

Mob: 07956 318 454

top of page